“Old Bill” Schilling would have loved this August Historic Happenings column. That is because I am going to tell you a lot about his contributions to the town of Northfield during his 65 years here. And if there was anything “Old Bill” (as he referred to himself in later years) liked, it was talking about himself.

William F. (Bill) Schilling was born in Hutchinson on Nov. 11, 1872, to William and Mary (Lallier) Schilling. He was the third of 13 children and he wrote that “This all happened so as to not disappoint a relative. Uncle Louie, a baker, at the wedding wished my parents a baker’s dozen children…Uncle Louie, a piker, only had 11.”

The Schilling family lived in the village where Bill’s father was proprietor of a hardware store but they kept a couple cows in a nearby barn for their growing family’s dairy needs. This sparked his interest in farming and he wrote that his early aim was to “buy a small piece of land to develop my agricultural ideas.”

When his family moved to St. Paul where his mother had been raised, Bill Schilling dropped out of school and became a printer’s devil (apprentice) at the Hutchinson Leader. He earned $2.50 a week for three years, boarding with an older sister for $2 a week, leaving him 50 cents spending money, which he felt worked out just fine. However, he would occasionally write with humor about his lack of formal education and his lingering regret that he did not graduate with the Hutchinson High School Class of 1886.

After his apprenticeship, Schilling moved to St. Paul, taking printing jobs there until 1892, when he became foreman of the Appleton (Minn.) Press. Three years later, the Press reported that he had accepted “a more remunerative position on the Northfield News.” The Press congratulated him on his advancement and called him “an active industrious young man of more than ordinary ability.” Schilling was a welcome addition to the Northfield News starting on April 5, 1895, as foreman and then editor during the four terms Joel Heatwole, the publisher, was serving in Congress.

Schilling wrote, “Coming to Northfield was like coming home. The beautiful trees lining practically every residence street of the neat little city and the excellent stores with a polyglot population furnished an admixture good for the stability of the place.” He said, “The city and its people were of the give and take kind and made me feel at home from the very start.” He married Northfield schoolteacher Margaret D. Hanneman on July 22, 1899, saying that it took years of “steady attention to convince her that it would be a profitable proposition for her to give up a $55 a month job for a Schilling.”

Schilling soon set out to convince area farmers that they must “dairy or die” in the face of the devastation wrought by cinch bugs on the wheat crops and worms among oat fields. Schilling promoted the idea that farmers should specialize in purebred Holstein cows. He practiced what he preached when he rented Spring Brook Farm southwest of Northfield from Heatwole in 1904 and then bought it after Heatwole’s death in 1910. (Heatwole had told Schilling that the paper was “beginning to smell like cows” in the wake of Schilling’s advocacy but had supported Schilling’s stance by establishing a separate dairy paper which Schilling edited.)

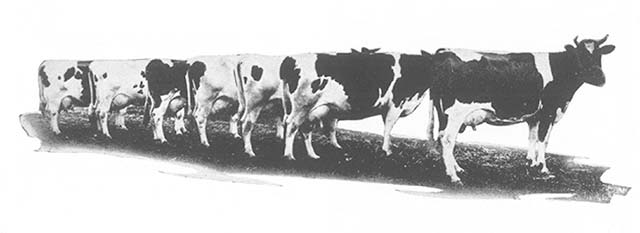

By the time The History of Rice and Steele Counties, Minnesota, was printed in 1910, Schilling was described as an “excellent type of the modern and scientific farmer,” whose Spring Brook Farm was “one of the show places of the county.” He was at that time president of the Minnesota State Dairyman’s Association and leader of the Holstein-Friesian Association of America. His cow, Esther Piebe De Kol, Second, of his herd was the “champion cow in the state” with a “record of 29.43 pounds of butter in seven days, 114 pounds in 30 days and an average of 98 pounds of milk for 43 days.” This record inspired many new herds in the community and state and Northfield became known as the Holstein center of the Northwest and, in 1914, adopted “Cows, Colleges and Contentment” as the town slogan.

Schilling left editing behind (while continuing to write columns for Northfield papers until 1957) and became president of the Twin City Milk Producers Association from 1917 to 1928 and director of the Land O’Lakes cooperative from 1911 to 1928. He was appointed by President Hoover to be the dairy member of the Federal Farm Board in 1929 and U.S. representative to the International Dairy Congress in London, after which he visited 12 countries. By his count, he made more than 5,000 speeches in every state in the U.S. for better dairying and helped organize 72 co-operative creameries and milk associations.

In the course of his extensive travels, Schilling amassed an eclectic collection of things from all over the world. His hobby of collecting started in 1893 when he was city editor of the Appleton Press and he hired a hobo at 75 cents a week to run the press. Schilling advanced the man a week’s pay, and the hobo left a security of a beautiful Sheffield (English) dagger in a leather case but took off and never returned for it. Schilling began collecting other daggers and then guns of every sort as he gave speeches throughout the country, eventually accumulating hundreds of guns and daggers. (Among his finds: a double-barreled gun once owned by Louis XIV, King of France, and a .50 caliber elephant gun for hunting big game in Africa, “guaranteed to stop an elephant at 200 yards.”) When he was in Washington, D.C., on the Federal Farm Board, he started collecting furniture and other items such as china, silverware and carvings from other countries. Among these items was an “old flower pot” of silver which he bought for a “nominal sum,” later finding possible authentication that it dated back to 1500 BC.

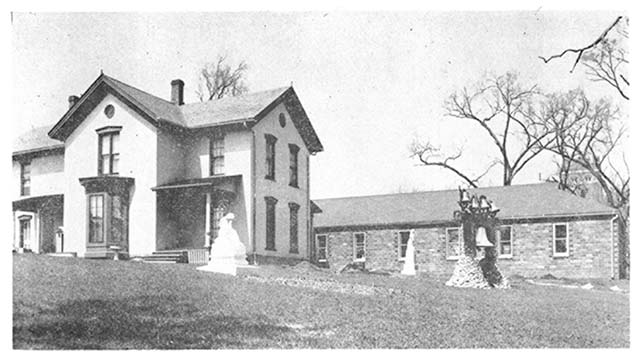

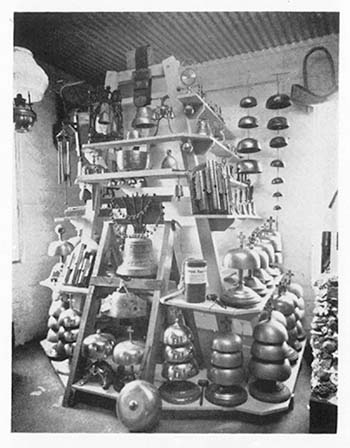

In the spring of 1942, Schilling erected an 84-foot long building on Spring Brook Farm to house his ever-growing collection. An Aug. 6, 1942, story in the Northfield Independent said that Schilling’s “Hobby House” was attracting attention with its displays of 500 weapons, including, guns, daggers, pistols, spears of headhunters, relics from ancient Egyptian tombs, carved woodwork from the Orient, household utensils of Northwest pioneers, lamps, vases, dishes, wine sets used by early French families in New Orleans, a melodeon from the Stanton Methodist Church and items brought by immigrant families. The entrance door was hung on wrought iron hinges from the engine room of the Archibald Mill of Dundas, a gift from J. A. DeMann of Dundas. There was a small chapel, only 10 by 14 feet, representing the Catholic church in pioneer days. This article concluded by saying that Schilling was not a “gentleman farmer,” but a true “dirt farmer,” who “has done his full share in milking cows, slopping hogs, fighting weeds, and doing the everyday farm work.”

In May of 1945, having sold Spring Brook Farm to St. Olaf College, Schilling bought property on Poplar and West Fourth streets on Northfield’s west side as a home and new hobby house with his wife Ann Graff, whom he had married three years after the death of his first wife in 1936. The 11-room brick house they moved into had been built in the 1860s by Linus Fox, who started a foundry and machine shop. (Schilling promoted this house as being haunted, available for tours.) He hoped building a museum in Northfield would “make it accessible to many more people” and in a booklet he wrote in 1958 for visitors, Schilling wrote that he had “the greatest display of foreign and domestic articles in America owned in a private showing.” Several hours would be required “for just a casual glance” at more than 20,000 articles in 116 show cases from his lifetime of travel through 48 states and 14 foreign countries. He stressed this was not “junk from wood sheds.” The museum, with its annex erected in 1957, included another small St. Francis’ Chapel, this one 14 by 14 feet, built in honor of his daughter, Sister Margaret Francis who in 1958 was superintendent of nurses at St. Mary’s Hospital in Minneapolis.

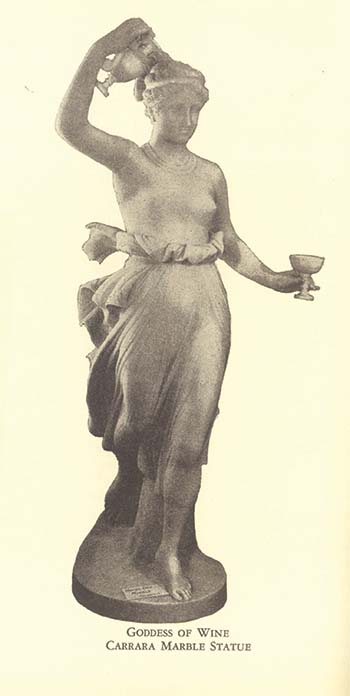

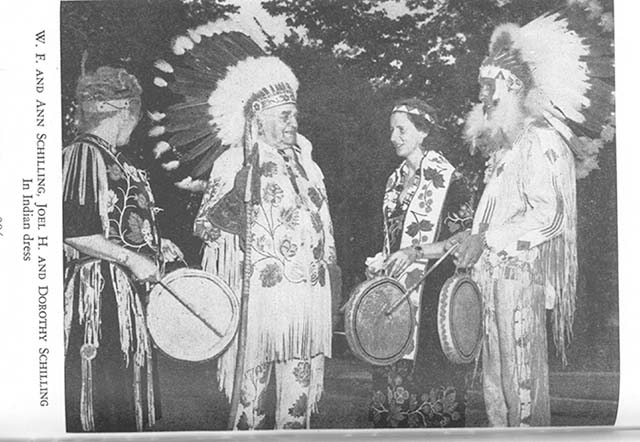

On May 8, 1947, young Northfield News writer Margaret (Maggie) Lee wrote that the new hobby house was filled with antiques and curios that attracted many visitors. She reported that on display was a solid bird’s eye maple bedroom set which had belonged to Minnesota’s pioneer Episcopal Bishop Henry B. Whipple, founder of the first Protestant cathedral in America at Faribault. She took note of the five bells in the front yard: four locomotive bells from the Great Northern, Omaha, Rock Island and Milwaukee railroads and the old 685-pound Dundas village bell. Lee said that “Four huge show cases of Indian suits, ornaments and implements of war are very attractive.” Lee (who would later be known in town for her collection of cat items) said there were 200 dog figurines, vases from all over the world, furniture used by the rulers of Austria that had been constructed by craftsmen from 1619 to 1721, a set of china used by the family of Napoleon Bonaparte, John Philip Sousa’s baton, eight Carrara marble figures, a ten-gallon hat worn by the Mexican bandit Pancho Villa when he was shot from his horse, a chair favored by Abraham Lincoln, three white tablemats made by Lincoln’s mother and items related to the 1876 attempted robbery of the First National Bank in Northfield by the James-Younger Gang.

Within just a few years of opening this new hobby house, Schilling was chiding Northfield in a full-page discourse in the Northfield News of March 3, 1949, for not visiting the “wonderful display” others were coming from near and far to see. “Visitors from Faribault outnumber the home folks at least 25 to one,” he griped. Schilling also had a grudge about taxes. “The Hobby House is an educational institution just as are the two colleges but the tax collector does not think so.” Schilling had to pay taxes on the 50 cent admission he had charged 1,200 visitors from the previous summer. In a parting jab, Schilling noted his Hobby House had dining room furniture used for seven generations by the royal family of Vienna and “you do not have to go to Vienna to see it.” He said, “Get in your car and drive 50 miles,” then turn around and return to Northfield to see this exhibit “any day, any time up till 8:00 at night.”

In 1950, Schilling added a replica of the Statue of Liberty to his lawn, a copper statue from Chicago, which he said was one-sixteenth the size of the one in New York harbor. Around it, he put 40 bells from locomotives that he had solicited from railroad presidents.

Schilling dedicated his last years to tending to the museum and fostering a bitterness toward the local press. When Schilling died on Feb. 11, 1960, an extensive obituary appeared in the Northfield Independent of Feb. 15, with the headline, “Death Stills the Trenchant Pen of W.F. Schilling. Former Leader was Columnist, Public Speaker, Collector.” It was written by Carl Weicht, who had enraged Schilling in the summer of 1957 by not printing something adversarial that Schilling had written about an outdoor public swimming pool project that Weicht favored. Weicht, who had become editor of the Northfield News in 1956 and brought together as “twin weeklies” both the News and the Northfield Independent, wrote that “When he became a columnist he felt he should be the sole judge of what was proper to be printed and he was invariably irked when the editors for whose papers he wrote undertook to correct the spelling, insert a verb where none was before, or lighten the shafts of his attacks with a drop of the milk of human kindness. He often accused them of ‘taking out all the Schilling.’ In this he was not unlike most spirited columnists who regard their editors and the publishers who foot the bill as slightly stuffy.” Weicht said Schilling would switch back and forth writing for newspapers, “depending on which local editor he was at odds with.”

Once the two newspapers were united under one editor (Weicht), Schilling had nowhere to go and simply terminated his column, Tales of the Town and Countryside, with his last column appearing in the Independent on July 8, 1957. He then privately printed a four-page tabloid-sized newspaper, featuring his own obituary with, as Weicht characterized it, “the obvious implication that no editor with whom he had any intimate association during his lifetime could do him justice in the end.” Schilling attacked Weicht as the “Little Caesar” who had issued an edict that “he is to be the judge of what is going in his papers” and Schilling mocked the combined papers as “Twin Weaklies,” as he laid out the achievements of his life in his own obituary.

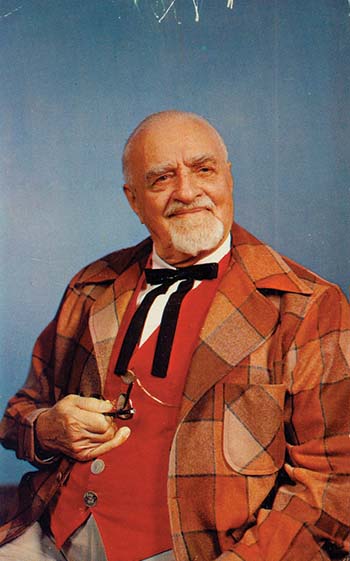

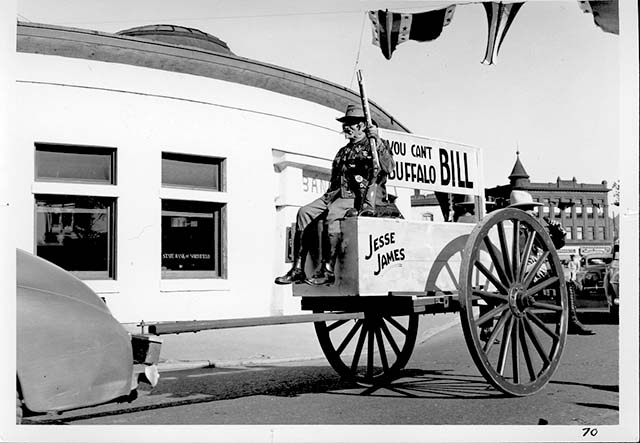

Weicht wrote that Schilling thrived on “personal controversy” and that “Age did not mellow ‘Old Bill,’ as he referred to himself, however much the years brought their picturesque touch as he more and more assumed the attire and the attitude of a homespun ‘Buffalo Bill.’” Weicht concluded, “For his community, its activities and its people, big and little, he retained an unflagging interest and an indefatigable activity. He was just as busy at 87 as he was at 40.”

Schilling had hoped his collection could be kept together forever. He once wrote, “A good hobbyist almost never sells an article that he has a fondness for collecting. He may trade with others to make a more perfect collection but to sell – that is the job of the professional antique dealer.” After his death, the museum was carried on by Schilling’s second wife Ann (who died in March of 1968) and Schilling’s son Louis and wife Alice.

Finally, the museum was closed and the contents sold at auction May 6 through 10, 1981, at the Antique Resource Center in Golden Valley.

The Schillings had previously donated a variety of memorabilia to the Northfield Historical Society and gave even more just prior to the auction. Among the items given that related to the famous Northfield bank raid of 1876 were the 6,580 pound Evans & Watson safe of Philadelphia that was inside the vault at the First National Bank, the clock that was on the wall, Cole Younger’s written response to the Rice County Sheriff when asked to tell which of the raiders killed Joseph Lee Heywood inside the bank (“Be true to your friends if the Heavens fall”) and a dried ear and part of a scalp of one of the bandits (Yes, really! Schilling said it belonged to Charlie Pitts, but DNA testing may yet determine whose ear it is. It is currently in the “40 for 40” exhibit at the Northfield Historical Society.)

The Northfield News of April 16, 1981, reported that after Schilling’s Indian collection was displayed at an advance showing at the auction house, “both environmentalists and Indian activists complained about the planned sale of feather headdresses” because “federal law prevents the sale of items containing the feather of an eagle, an endangered species.” The two headdresses were then donated to the Northfield Historical Society.

Maggie Lee, a founder of the Northfield Historical Society and Northfield News editor, participated in the auction and wrote on May 14, 1981, about obtaining one of two chairs that had been used in the home of John North, founder of Northfield. Since the chairs dated back to the 1850s and were “hard used,” she was “somewhat unhappy” at her accepted bid of $60 for one but was amazed when the second one fetched more than $100. (The North chair is also currently part of the Northfield Historical Society’s “40 for 40” exhibit.)

Schilling once wrote that the James-Younger Gang “must have brought a wagon load of guns to pass out as souvenirs of the occasion” because so many people claimed to have guns used by the robbers. There were three authenticated guns in the Schilling collection which were connected to the raiders and were included in the auction. It did not appear likely that the Northfield Historical Society, just formed in 1975, would have sufficient funds to obtain any of these guns for their museum. The Society, according to a story in the Northfield News of May 21, 1981, was “deeply in debt for construction and building purchase” of the Scriver Building and was launching a drive for funds to finish paying for the restored bank front and attempting to reduce its mortgage, with a goal of $50,000.

Northwestern State Bank and local ophthalmologist Dr. Ronald Linde came to the rescue. The bank loaned money for a successful bid on the .44 caliber Smith & Wesson “Black Russian” model revolver taken by police after the raid, along with the cartridge belt and holster. (Schilling said it had belonged to Charlie Pitts, the gang member who was killed in Madelia two weeks after the raid and that Schilling had gotten it from a young Minnesota Historical Society employee in 1947 who had been told to throw this “implement of destruction” in the furnace.) This gun had been used as evidence at the Younger Brothers’ trial. Linde provided funds for the Moore .32 caliber Rim Fire revolver with holster which had been taken from robber Cole Younger by the posse which captured him and his brothers Bob and Jim after the shootout at Madelia. With the state sales tax and auctioneer’s fee, Linde’s purchase came to nearly $9,000, while the Smith & Wesson gun sold for $11,000 plus tax and fee.

Linde, who has had a medical practice in Northfield since 1975, recently showed me an insurance letter from May 12, 1981, which gave an evaluation of these two guns as then worth $15,000 each. He had felt that because of the historical significance of the gun, it was important that the gun stay in Northfield rather than going to a private collection where it could be out of sight for generations. Linde loaned the gun to the Northfield Historical Society for display and then donated the gun and holster to the Society, effective December 31, 1986.

Schilling also contributed to the history of Northfield through his many writings, including five books and many columns and articles about days gone by. In 1935, in Up and Down Main Street 40 Years Ago, Schilling captured life at the turn of the century in Northfield. But his favorite subject (besides cows) was himself. He loved sounding off on everything under the sun, giving views which often sound quaint indeed today. Here are some examples from Schilling’s books My First Eighty Years and It’s Good Business to Marry School Teachers or Nurses.

“Number one bet in picking a wife is to get a school teacher between 23 and 30 and then you have something worth while. By that time she has learned how to handle other folks’ kids and has earned a chance to have a few of her own.” Teachers, he has found from experience, “let go their primness” during horse and buggy rides at night. Schilling also advocates choosing “an old maid” who is “always very grateful” and, as a rule, has not been “pawed over and messed up like the common run of the species.”

“Men prefer blondes?” Oh, yes, writes Schilling. Blondes are “generally more fickle and also susceptible to flattery and less dangerous to get rid of when occasion presents itself.” As for a “darker-haired Jane” – she is quite hard to deal with “if her affections are being trifled with. In fact she will both bite and scratch and make trouble enough to last for quite a while.”

Another observation: “I am living in a college town and all about me are married couples that seem perfectly healthy but they are childless.” The reason? Twin beds, according to Schilling. Schilling also asserts that “college presidents do not reproduce themselves or their likenesses to the nth degree.” In particular, only two of Carleton’s four presidents in the past 75 years produced offspring. Schilling writes, “Now to me this is pitiable for as an old farmer and wanting always the best stock from the best foundation stock we could find I am puzzled at the lack of ability of these great men to reproduce their kind.”

But Schilling does have some sound advice to offer: “If you want to know what my life’s motto is, I will tell you: It is work, more work…If you are a doctor, lawyer, merchant, preacher or a carpenter or bum just struggle to be the best in your class. If your work be a pleasure you will never grow old, but have a hobby of some sort for recreation and vacation.”

A stanza of a poem Schilling wrote seems like a fitting ending to this column:

What care I, if when I’m dead the local papers get

For me a flowery write-up and a cut in mourning set.

It will not flatter me a bit, no matter what is said,

So pass to me the flowers now and knock me when I’m dead.

I never had the chance to pass flowers to Bill Schilling because I first came to Northfield to attend St. Olaf more than four years after his death. But here is a Historic Happenings write-up for you, Bill, with flowers and thanks for your contributions to community history here.