Kenneth and Carolyn Jennings are my neighbors at Village on the Cannon. So, before they left for their winter sojourn in Arizona, it was my pleasure to make a short 60-step trip down the hall for this column. In this month of December, St. Olaf College is celebrating 100 years of its renowned Christmas Festival, with a special exhibit at the Northfield Historical Society. Ken Jennings is one of only four men to have directed the St. Olaf Choir since F. Melius Christiansen took the St. John’s Church Choir on a tour of Wisconsin and Illinois in 1912 as the newly christened “St. Olaf Choir.”

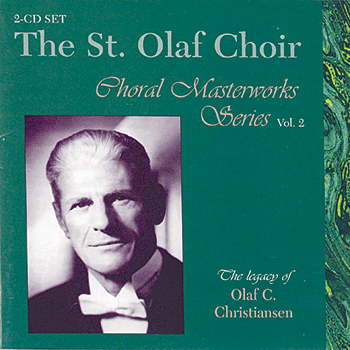

Christiansen, who had emigrated from Norway in 1888, was hired as the college’s first director of music in 1903. By the time he turned over the reigns to the Choir to his son Olaf in 1943, he had established the St. Olaf Choir as the gold standard of college choirs, a distinction carried on after Olaf Christiansen by Jennings from 1968-1990 and since 1990 by Anton Armstrong.

“What inspired me most to come to St. Olaf was Luther Onerheim,” Jennings told me. Onerheim was a graduate of the Class of 1937 and founder of the Viking Male Chorus on campus. Jennings, a native of Connecticut, went into the Army after graduating from Westport High School in 1943 and met Onerheim, a musician and chaplain’s assistant at Ft. Benning, Georgia. Basically a trumpet player, Onerheim was happy to have Jennings play organ in the chapel services. Onerheim was “a most interesting and charismatic person that could draw people to him,” said Jennings. Without trepidation, Pfc. Onerheim “went in to see the colonel and said he wanted to form a chorus,” said Jennings and he requested rehearsal time for the singers. Jennings sang in this Fifth Infantry (71st Division) choral group, which became known as the Soldier Chorus. The Chorus entertained troops in Europe at the end of World War II. Based in Augsburg, Germany, after V-E day, the Soldier Chorus continued its musical mission, including a performance at the first post-war Salzburg Music Festival on Sept. 2, 1945.

Unfortunately, Onerheim was killed in a jeep accident on Jan. 16, 1946. Back in the United States that May, Jennings visited Onherheim’s widow Jane near his home in Connecticut. She encouraged him to apply to St. Olaf. With many applicants taking advantage of the GI Bill, Jennings’ application was put in a file for the next year at St. Olaf.

So he headed by train for Colorado College where he had been accepted, but he decided to take a detour to visit Northfield.

Suitcase in hand, Jennings got off the train in the pouring rain. (“I was just soaked,” said Jennings.) His thought was that if St. Olaf would not take a chance on him, “I’d take a look at Carleton across the river.” The dean of men at St. Olaf, Cully Swanson, looked over his credentials in the file and “thought I’d be a good enough risk,” said Jennings. So he stayed.

“Everyone sings at St. Olaf,” Olaf Christiansen would say when leading songs at Chapel services. There was a corollary saying, “Everyone auditions for the Choir at St. Olaf,” and Jennings said that some of the students “auditioned for the choir whether they wanted to or not.” Jennings, an accomplished pianist, was accepted in the music program and sang in the St. Olaf Choir all four years. At a gathering last June of past Choir members celebrating 100 years of the Choir, Jennings recounted his audition.

“I thought I was a baritone, but found my name on the tenor recall list,” said Jennings. “Dr. Christiansen would play a pattern or a tune and start at one end of the line or the other. But somehow, from either end, it never got to me. Finally there was one tune that had one elusive note that everyone kept missing…Olaf swung around and pointed at me – and I sang the note. ONE NOTE! I was in the Choir! For all anyone knew, it might have been the only note I could sing!”

During the first weeks at college, Jennings and his roommate had the opportunity to visit F. Melius Christiansen at his home. Jennings describes the Choir founder as a “delightful, cherubic, good-humored person, very easy to talk to.” When offered coffee, Jennings told me that he thought to himself, “Here’s my chance. I’d heard about Norwegian egg coffee.” To his surprise, “it was just Sanka.”

Jennings recalled that F. Melius Christiansen “would come to choir rehearsals quite often when Olaf was conducting.” (Olaf had taken over from his father in 1943, after two years as associate director.) During a rehearsal, on occasion, Olaf would turn around to his father and say, “How do you like THAT, Grandpa?” which would cause F. Melius to “just light up,” beaming with his “flashing blue eyes,” said Jennings.

Olaf Christiansen had sung in the St. Olaf Choir directed by his father, graduating in 1925. He returned to St. Olaf in 1941 after teaching and choral conducting at the Oberlin Conservatory of Music in Ohio. Olaf Christiansen was tall and slender, athletic, a gymnast who could “stand on his hands,” said Jennings. Olaf was somewhat austere and more formal than his father, and Jennings described Olaf’s approach to music as “less romantic, more classic and tidier,” with an “extremely clear” sound.

Jennings’ years with the Choir under Olaf Christiansen included tours of both coasts and the Midwest. Jennings graduated magna cum laude in 1950 with a Bachelor of Music degree. He went on to get a Master of Music degree in 1951 at Oberlin Conservatory of Music and chaired the music department at Mitchell College in Statesville, North Carolina, from 1951 to ’53 before returning as a faculty member to his alma mater St. Olaf in 1953. In 1966 Jennings earned a Doctor of Musical Arts degree from the University of Illinois.

Besides teaching music and giving voice lessons at St. Olaf, Jennings directed the Manitou Singers his first year and then started directing the Chapel Choir the next year where he initiated major choral/instrumental works. As Joseph Shaw described it in his 1997 book The St. Olaf Choir, “The 12 and a half years as director of the St. Olaf Chapel Choir was more than an apprenticeship for the man who would be selected as the third director of the St. Olaf Choir in 1967…As a larger choral ensemble of 90 to 100 voices, with no binding commitment to a cappella singing or memorizing all of its music, the Chapel Choir was in a position to take on larger, longer works that could be performed with organ, piano, or full orchestra.” Among the many larger works performed with the St. Olaf Orchestra were Bach’s St. Matthew Passion and St. John Passion, Faure’s Requiem and Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms.

When Jennings took over the St. Olaf Choir from Olaf Christiansen in 1968, he was prepared to add not only longer works to the repertoire but a new style of singing. While respectful of the past, Jennings told me he wanted to give the Choir members “more freedom to be more expressive, individually” because “I felt it would refresh the sound of the Choir.” Jennings recalled telling one of his soloists, “Ginny, I want to hear YOUR singing, your voice, not what you think somebody wants to hear.” (Soprano soloist Ginny Bergquist, class of 1970, later wrote that his remark was liberating, “truly the best gift of all.”) This new tone of the Choir is summed up in Shaw’s book as “elegant naturalness,” with “a tone reminiscent of the earlier sound of the Choir but yet one with less rigidity, greater freedom and flexibility, and a new warmth.”

Jennings was open to a new expanded repertory of the 20th century, starting with his first year as director when Penderecki’s I Will Extol Thee and Schoenberg’s De Profundis were in the program of the Choir’s 1969 tour. The latter is a 12-tone piece combining dramatic spoken words (sprechstimme) with singing which Jennings and Olaf Christiansen had heard performed the previous spring in Minneapolis by the Oberlin Choir. The retiring director told Jennings, “You could do that piece.” They could indeed, with the work receiving critical approbation on tour.

Jennings also added instruments at times to the Choir, since it “enlarged our repertoire possibilities.” Flute and guitar were used for Walter Pelz’ Who Shall Abide on the 1969 tour. Often the Choir did not have to look beyond its own members for instrumentation. Said Jennings, “We would sometimes have some quite good instrumentalists in the Choir, including some accomplished string players.”

Jennings also added instruments at times to the Choir, since it “enlarged our repertoire possibilities.” Flute and guitar were used for Walter Pelz’ Who Shall Abide on the 1969 tour. Often the Choir did not have to look beyond its own members for instrumentation. Said Jennings, “We would sometimes have some quite good instrumentalists in the Choir, including some accomplished string players.”

The Choir had shared billing with the Minnesota Orchestra for many years but with separate performances on the same program. From the beginning of Jennings’ career with the Choir and stretching over two decades, Jennings directed the Choir in a dozen major works with the Minnesota Orchestra under Stanislaw Skrowaczewski and Neville Marriner. In 1978 the Choir helped the Minnesota Orchestra celebrate its 75th anniversary in a concert in New York’s famed Carnegie Hall, performing Ravel’s Daphnis and Chloe to much acclaim. In 1985 the Choir teamed up once again with the Minnesota Orchestra with concerts in Carnegie Hall and the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C.

When Jennings retired in 1990, Skrowaczewski wrote, “I will never forget the beauty of tone in the works that we did together…You have spoiled my ear and taste to the point that after collaborating with your choir, no other choir in the world that I work with could give me such satisfaction.”

During Jennings’ tenure with the Choir, annual domestic tours continued and summer tours abroad increased in number. In 1970 the St. Olaf Choir was the only non-professional group to take part in the International Strasbourg Festival during the Choir’s trip to France, Holland and Germany. The 1972 tour of France, Belgium and Switzerland was highlighted by the St. Olaf Choir being given the honor of opening the 1972 Strasbourg Festival with Bach’s Mass in B-Minor with the Strasbourg Philharmonic at the Strasbourg Cathedral.

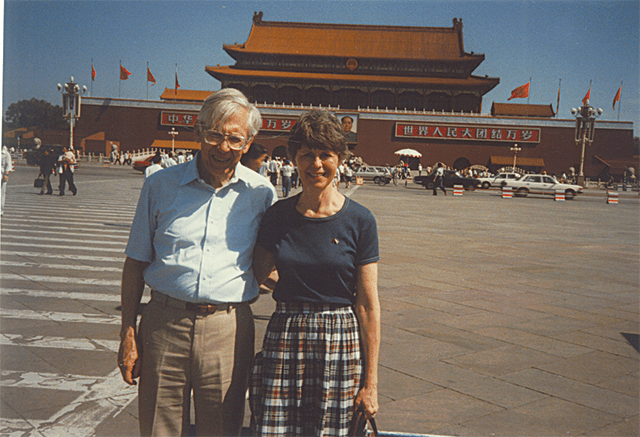

The 75th anniversary of the Choir in 1986 was celebrated with a trip to the Orient to Japan, Taiwan, Hong Kong and the People’s Republic of China. The Choir mastered singing pieces in ten different languages for this tour, a feat which was much appreciated by the audiences who would become especially excited and applaud when they heard the songs in their native tongues. Jennings noted they were always under the scrutiny of authorities in China. Although he had to be careful “to keep the name Jesus out of the texts,” when they handed out recordings after one concert, they did give out copies of the Beautiful Savior record because that was all they had left. (F. Melius Christiansen’s well-known arrangement of Beautiful Savior has long been associated with St. Olaf. The work has a “unique emotional quality” which pulls singers and listeners together into a “complete wholeness,” in Jennings’ words.)

The St. Olaf Choir had the distinction of opening the International Choral Festival of the “Seoul Olympic Arts Festival” of Korea in August of 1988, the only American choir invited to participate. The Choir joined with four other international choral groups and five Korean choirs in a massed choir performance at the end with the Korean Philharmonic Orchestra.

The Choir headed east in 1990 for Jennings’ final concert tour as director, including performances in Orchestra Hall in Chicago, Carnegie Hall and the Kennedy Center yet again and concluding with a recognition banquet and concert in Minneapolis.

Jennings was succeeded as director in 1990 by Calvin College music professor Anton Armstrong, St. Olaf Class of 1978, who had sung in the St. Olaf Choir under Ken Jennings. Armstrong continues as director today.

Ken and Carolyn Jennings have three children. Steven is on the faculty of McNally Smith College of Music in St. Paul and is a professional musician who lives in Northfield. Lisa sang in the St. Olaf Choir when her father was directing and is on the German faculty at Valparaiso University in Indiana. Mark also sang in the St. Olaf Choir under his father and is director of choral activities at Truman State University, Kirksville, Missouri.

Ken and Carolyn Jennings, who met when she joined the St. Olaf faculty in 1960 as a piano instructor, were married in 1962 in Boe Memorial Chapel, with Olaf Christiansen conducting the Chapel Choir. Carolyn Jennings has written more than 100 compositions, including many commissioned works, and was chair of the St. Olaf Music Department 1991-97.

In a 1925 interview, F. Melius Christiansen said, “It is necessary for us to realize that musical expression, if it is sincere, must change to a certain extent with the changes in the thought and outlook of succeeding generations.”

Ken Jennings provided a perfect coda: “Each conductor has had a different approach to the St. Olaf Choir, but the essence of the Choir – its sharing of beauty and meaning through music – continues in a long unbroken line. And the message of praise and love of God continues to be shared here and across the land and the world.”

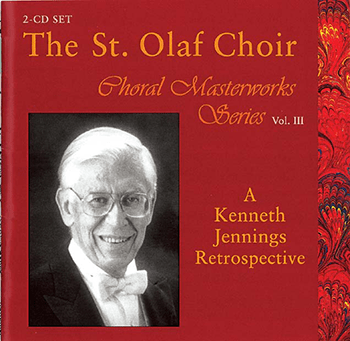

My thanks to Ken and Carolyn Jennings for sharing their memories, insights and photographs with me for this column and to Joe Shaw, whose book The St. Olaf Choir: A Narrative, published by St. Olaf College in 1997, was a primary source of information. Recordings of the St. Olaf Choir are available at the college bookstore and through stolafrecords.com.