On Sunday, Feb. 26, 2012 Northfielders had a chance to experience what it would have been like to be in an “electric theater” audience when the town first was wowed by moving pictures, later called “movies.” This show was held at the Weitz Center for Creativity. It was sponsored by the Northfield Historical Society, the Humanities Center at Carleton College, the Carleton Cinema and Media Studies Dept., the Northfield News and KYMN Radio.

Carol Donelan, Associate Professor of Cinema and Media Studies, narrated a guided tour of Northfield’s movie history through the late 19th and early 20th centuries, starting with the type of show brought to Lockwood’s Opera House in March of 1897 by the Kickapoo Indian Medicine Company. Back then, about 400 people paid the “popular price” of 10 cents (which included a drawing for a $20 silver tea set) to see the featured attraction of Edison’s Animatograph machine, which projected moving pictures of a cavalry troop galloping toward the audience and a mail train flying past a station. Although admission was free to the Feb. 26 event, Gustave Petersen (aka Dr. Visty, a local charlatan and snake-oil salesman) promoted sales of “Kickapoo Indian Sagwa, the Blood, Liver, Stomach and Kidney Renovator,” as was customary at such shows. Hold onto your wallets.

Carol Donelan, Associate Professor of Cinema and Media Studies, narrated a guided tour of Northfield’s movie history through the late 19th and early 20th centuries, starting with the type of show brought to Lockwood’s Opera House in March of 1897 by the Kickapoo Indian Medicine Company. Back then, about 400 people paid the “popular price” of 10 cents (which included a drawing for a $20 silver tea set) to see the featured attraction of Edison’s Animatograph machine, which projected moving pictures of a cavalry troop galloping toward the audience and a mail train flying past a station. Although admission was free to the Feb. 26 event, Gustave Petersen (aka Dr. Visty, a local charlatan and snake-oil salesman) promoted sales of “Kickapoo Indian Sagwa, the Blood, Liver, Stomach and Kidney Renovator,” as was customary at such shows. Hold onto your wallets.

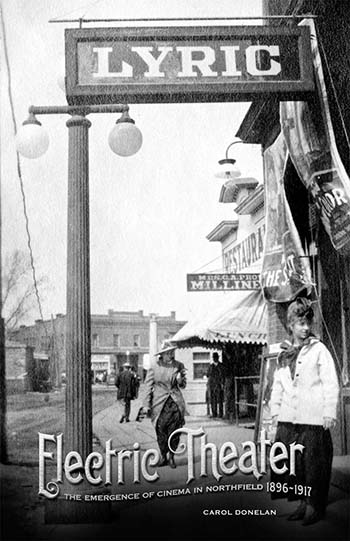

Donelan illustrated local moviegoing experiences taken from her new book, Electric Theater: The Emergence of Cinema in Northfield 1896-1917. This book was published by the Northfield Historical Society Press in 2011 as the third book in the NHS History Series in memory of Barbara Will.

Donelan illustrated local moviegoing experiences taken from her new book, Electric Theater: The Emergence of Cinema in Northfield 1896-1917. This book was published by the Northfield Historical Society Press in 2011 as the third book in the NHS History Series in memory of Barbara Will.

The Lumiere brothers of France first projected images onto screens in March of 1895. Donelan writes that the first moving pictures in Northfield were reported in the Northfield News of Nov. 21, 1896. The projection device, the Animatograph, was described as a “unique novelty…one of the greatest amusement devices ever conceived by the brain of man.” Tickets were 25 and 35 cents, steep for those times. A St. Olaf student recalled seeing moving pictures of a puffing, chugging steam engine, most likely at Lockwood’s Opera House, located above Couper’s Grocery and Dry Goods at 419 Division St. This “opera house” (so named because of derogatory connotations of “theater” in those days) dated from 1872 and was stuffy with a small stage and uncomfortable wooden chairs. Donelan writes that performances there ranged from high brow to “mostly low brow, including bell ringers, singers, comedians, minstrels, and melodramas performed by traveling troupes as well as blackface comedy and an annual standing-room-only St. Patrick’s Day drama by local talent.”

The opening of the magnificent 800-seat Ware Auditorium at the corner of Washington and Fourth Streets in December of 1899 led to replacement of Lockwood’s Opera House as a performing space for plays, debates, lectures and eventually for movies. Alfred Kirkland Ware was a businessman who had come to Northfield to enroll his children at Carleton. Owner of all the stock in Northfield Light, Heat & Power Co., he became mayor in 1902 and a state legislator in 1904. Ware Auditorium cost him $20,000 to build as a present for his theater-loving wife. He could afford it, as Donelan notes, since he had also spent $10,000 on “one of the most famous stallions in the world, Alcantara, for whom his 81-acre stock farm near Northfield was named.”

Donelan observes, “From 1896 to 1908, film exhibition in Northfield is largely the work of itinerant showmen rather than hometown entrepreneurs.” Motion pictures were first reported at Ware Auditorium on March 14 and 15, 1904. The touring International Bioscope Company projected such “new and intensely thrilling” films as Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Little Red Riding Hood, The Great English Stag Hunt, Captain Nissen Going Through the Niagara Whirlpool and Rapids and A Panoramic View of Switzerland from a Railway Train. These were advertised as being “without the constant flickering which usually accompanies such productions and which proves a severe strain to the eyes.”

In June of 1904, exhibitor D.W. Robertson brought two films by director Edwin S. Porter to Northfield, Life of an American Fireman, and the blockbuster hit, The Great Train Robbery. Donelan writes that The Great Train Robbery “helped pave the way” for the “nickelodeon boom” of storefront motion picture theaters which followed in 1905-07 in big cities and 1908-1910 in Northfield. The company of another exhibitor, Lyman H. Howe, brought the world to Northfield from 1909 to 1920 in the form of educational travelogues, with topics including “Dash for the North Pole,” “Eruption of Mt. Etna, “Perils of Climbing the Alps“ and “Aeroplane Races.” The motion pictures were accompanied by live sound produced by three “noise artists” behind the screen.

In June of 1904, exhibitor D.W. Robertson brought two films by director Edwin S. Porter to Northfield, Life of an American Fireman, and the blockbuster hit, The Great Train Robbery. Donelan writes that The Great Train Robbery “helped pave the way” for the “nickelodeon boom” of storefront motion picture theaters which followed in 1905-07 in big cities and 1908-1910 in Northfield. The company of another exhibitor, Lyman H. Howe, brought the world to Northfield from 1909 to 1920 in the form of educational travelogues, with topics including “Dash for the North Pole,” “Eruption of Mt. Etna, “Perils of Climbing the Alps“ and “Aeroplane Races.” The motion pictures were accompanied by live sound produced by three “noise artists” behind the screen.

Andrew Wyand of St. Paul had been proprietor of the Gem Theatre at the Ware Auditorium and on Aug. 19, 1909, he opened the 250-seat New Gem Theatre at 309 NW Water St, in the McClaughry Tenement. Donelan writes that it was the first venue in Northfield devoted exclusively to motion picture exhibition and featured the Blankenburg Family Orchestra as accompanists. However, the wooden frame building was torn down within a year to make way for the State Bank Building which opened for business on Aug. 27, 1910 (current site of the law office of Hvistendahl, Moersch, Dorsey and Hahn). Wyand briefly operated a new theater, the Star, on the corner of Division and 5th Street.

Fred W. Boll and his wife Maude, owners of The Grill at 302 NW Water St., became new proprietors of the Gem and relocated it to 306 NW Water St., next to the Ames Flour Mill. The city council denied a request to show films on Sundays. (In fact, Donelan writes that Sunday performances of any kind were not allowed in Northfield until June 2, 1931, after extensive debate.) The Bolls closed The Grill on Feb. 1, 1911, for a new enterprise, managing the Hotel Manawa at 211 S. Division St., which they renamed Boll’s Hotel. (It is now known as the Archer House, its original name in 1877.) That summer the Bolls opened an Airdome near the river in a park behind the hotel. The Airdome was lighted by electricity, could seat 500 people and had a large stage for vaudeville acts and an eight-foot canvas wall for motion pictures. Donelan notes that in September during county fair week (held at that time in Northfield), “fairgoers were treated to a musical trio and a troupe of trained alligators at the Airdome in addition to ‘tip-top’ reels of motion pictures.”

The Gem resumed operation in October and, after a remodeling in December which doubled the stage space, Maude Boll’s three-piece “ladies orchestra” accompanied movies while vaudeville reigned during holidays. By February of 1912, the success of the Gem led Boll to give up management of the hotel to G.R. Stuart, which led to the renaming, Hotel Stuart.

Donelan writes that between 1912 and 1915, “Italian super-spectacles were prevalent programming in Northfield’s electric theaters.” Crowds flocked to see epics such as The Crusaders, Dante’s Inferno, and The Last Days of Pompeii at the Gem and Homer’s Odyssey and Quo Vadis at the Ware Auditorium. About The Last Days of Pompeii, Donelan says, “Audiences in Northfield, as elsewhere, must have been thrilled by the spectacular scenes of the Vesuvius eruption, achieved with special effects and massive numbers of extras.” Donelan also notes the popularity of serials at this time: “These ‘cliffhangers,’ also known as ‘serial queen’ melodramas, featured intrepid heroines performing thrilling stunts and last-minute rescues traditionally assigned to male protagonists.”

In April of 1912, A.K. Ware (who had moved from Northfield to Oregon) offered to sell the Ware Auditorium to Northfield. Fund-raising efforts were successful and Harry Ackerman and Everett Dilley were engaged as managers, booking plays and motion pictures. Boll took over the lease in February of 1913, doing programming for both the Gem and the Auditorium.

Donelan writes that one evening at the Gem, “Boll lashed out at a group of rowdy St. Olaf students, casting aspersions on their Norwegian heritage.” The students circulated a “Boycott Boll” flyer on campus, saying that “when he disregards our bounteous patronage of the past with a slanderous oath, when he doggishly cusses the Norwegian race as such…let us as students of St. Olaf College, as descendants of the Norwegian blood of which we can justly be proud, hereby and forever resolve never to patronize the Gem Theater again…If we visit any movie, let it be The Lyric.” The 250-seat Lyric Theatre had emerged at 13 Mill Square (Bridge Square) in 1914. After a flurry of managers, the Lyric was closed by August of 1916.

In a chapter called “Northfield’s Movie-Mad Audiences,” Donelan describes packed movie houses and student aspirations to be movie stars. And yet, she says, “Some Northfielders were not so much ‘movie-mad’ as just plain mad – or at the very least concerned – about the kinds of movies show, the conditions of the theaters, and the impact on children and young people in particular.”

Donelan thoroughly researched the concern about movies which was particularly evident in Northfield newspapers of 1916. One resident asked why the Lyric found it necessary “to put on films which have a strong tendency to lead young boys and girls straight to the devil.” One Northfield News headline was “An Indictment of Movies, Eighty-five Percent of Films Shown in Small Towns Called ‘Rot.’”

Donelan reports, “The city council sought to address concerns about undesirable pictures and the conditions under which they were being shown at their March 1916 meeting, but the aldermen had not themselves attended the movies. Before the meeting adjourned, they informally agreed that they should visit the theaters and ‘get a personal view of the pictures thrown on the screen for our movie fans.’” By July, a committee had recommended a censorship board be established.

The Ware Auditorium was revamped by Dilley in January of 1917. It reopened on Feb. 5 under a new name, the Grand, with ownership by five men, including Dilley, who each invested $200. The city council announced it “would not grant licenses to any other theater as long as The Grand continues to give high class entertainments.” The Gem closed.

Electric Theater concludes with the chapter “Back to the Future,” which summarizes the subsequent history of cinema in Northfield. In 1918, a $3,500 Wurlitzer pipe organ displaced local musicians who had provided sound effects for films.

The first “talkie” (Gentlemen of the Press, starring Walter Huston) opened on July 11, 1929, two years after the premiere of the first talkie, The Jazz Singer, in New York. In 1937 Dilley built the West Theatre at 230 West Water St., which showed movies until 1958 when it was taken down along with other buildings for a rerouting of what is now State Highway 3.

The Grand Theatre, remembered fondly by many (including this columnist), survived as a movie theater until June 30, 1985. Appropriately, the last film was Code of Silence. (The Grand at 316 Washington Street is now used for many events, both public and private.) A multiplex theater, Southgate Cinema, closed down in 2008 and now houses Culver’s on S. Highway 3. Donelan writes: “Northfield no longer has a commercial cinema projecting films onto a big screen for collective viewing by a paying audience, as was the tradition for 100 + years.”

The 35mm celluloid technology is becoming a thing of the past as multiplexes are converting to high-definition digital projection at a cost of $75,000 to $100,000 per theater and, Donelan writes, “the few small town theaters in Minnesota, some family owned, will likely be unable to afford it.” Meanwhile, Donelan notes, Northfielders are “increasingly accessing films at home and on the go, on their cell phones, computer and television screens, via DVD, streaming and downloaded digital files.”

Nevertheless, the communal experience of moviegoing has been missed locally and Donelan tells me there are hopes that the theater in the Weitz Center for Creativity (the former Northfield Middle School at 320 Third St. E) will help fill that void. Donelan said that the “Living Electric Theater” event on Feb. 26, 2012 featured episodes from Northfield’s moviegoing history, “along with a stellar cast of local actors and musicians” and is free and open to the public.

Carol Donelan’s book Electric Theater is available for purchase at the Northfield Historical Society at 408 Division St. S. and the Carleton College Bookstore.