Originally Published in the February 2014 Entertainment Guide

When I spent my freshman year at St. Olaf in Hilleboe Hall, which was perched on a hill overlooking lovely Norway Valley at the southwest part of the campus, I do not recall asking about the source of the name of my dormitory. I spent my last three years at the newly built 12-story Agnes Larson Hall (which we called “the woman’s tower”) and did not think much about student housing names beyond that.

But after writing last month about Carleton’s Dean of Women Margaret Evans, who served from 1874 to 1908, I felt it only fair to write about St. Olaf’s Dean of Women, Gertrude Hilleboe, who served even longer, from 1915 to 1958. Both ladies had dormitories named after them and although Evans died in 1926, a year before her namesake dorm was occupied, Hilleboe had the distinction of living for a time in the dorm named after her. She retired as dean six years before my college days began but after I returned to live in Northfield in 2004, I attended several all-alumni gatherings where her name was often recalled, with an equal mix of respect, fondness, humor – and sometimes even exasperation. So, just who was Gertrude Hilleboe?

Hilleboe was born in Willmar, Minn., on March 18, 1888, into a family where education was valued. Her father, Hans S. Hilleboe, was, at this time, president of a church academy, Willmar Seminary. A Wisconsin-born son of Norwegian immigrants, Hans had a B.A. (1881) and M.A. (1886) from Luther College in Decorah, Iowa, and among his later positions were superintendent of public schools in Benson, Minn., principal of the Preparatory Department at Luther, president of Lutheran Normal School in Sioux Falls, S.D., and the first president of Augustana College 1918-1920 when the Normal School consolidated under that name in Sioux Falls. He continued on the Augustana faculty until 1933 and died in December of 1947 at the age of 89.

In Gertrude Hillboe’s memoir, Manitou Analecta (1968), she wrote, “There never was a time within my memory when my life was not in some way linked with St. Olaf.” Her mother, Antonilla Ytterboe, provided the link to St. Olaf. Antonilla was born to pioneer settlers of Winneshiek County, Ia., completed three terms at St. Olaf’s School in 1885 and married Hans, a Luther classmate of her brother, Halvor Ytterboe, in 1887. Halvor Ytterboe had been teaching at St. Olaf’s School since 1882. The Hilleboe family would stop by Northfield to see Halvor and his family in their quarters in what we now know as Old Main which was, in those days, not so old at all.

St. Olaf’s School, founded Nov. 6, 1874, by Norwegian immigrants, was first located in downtown Northfield at the corner of Union and 3rd streets in two old school houses. The Main, dedicated on Nov. 6, 1878, was the first campus building on what came to be called Manitou Heights, housing classrooms, students and teachers alike. Hilleboe recalled how impressed she was “by the high ceilings and tall windows with their elegant red velvet draperies” and how she and her cousins had fun running up and down the long stairs to the third floor. The Ytterboe name is revered at St. Olaf for Halvor Ytterboe’s dedication to saving the college by traveling to solicit funds far and wide during financial struggles of the 1890s. Then came true self-sacrifice: Ytterboe’s death at the age of 46 on Feb. 26, 1904, was attributed to his developing formaldehyde poisoning from fumigating the men’s dorm washroom during a scarlatina epidemic the previous year.

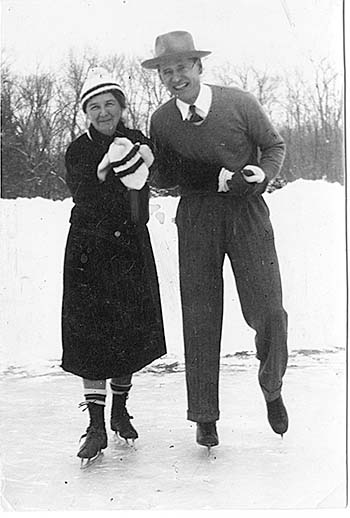

Young and short of stature, Gertrude Hilleboe (circa 1915) was called the “infant dean” when she attended a national deans’ meeting in New York in 1917. Photo courtesy St. Olaf College Archives.

Gertrude Hilleboe was valedictorian of her class at Benson High School and, after teaching elementary school, she enrolled at St. Olaf in 1908. After a break to teach again in Benson during her junior year, she returned and still managed to graduate with her Class of 1912. The Manitou Messenger of June, 1912, wrote of her: “As a student she stands alone and excels not only in one but in all lines. However, she is not satisfied with book learning alone but enters upon everything she undertakes with a vim and enthusiasm nothing can resist.”

Hilleboe was preceptress and teacher at Waldorf College in Forest City, Iowa, when St. Olaf President Lauritz A.Vigness wrote her early in 1915, asking her to teach Latin and take the position to be called “Dean of Women.” In a July 1, 1970, interview, Hilleboe told Dr. Joseph Shaw (who was writing the History of St. Olaf College), “I was overwhelmed. I couldn’t think of it. I had always thought of the mission field.” But she agreed to take the job for one year. She told Shaw, “I’ve felt eternally grateful to Dr. Vigness for encouraging a greenhorn like me to take this job. And see it grow.”

Although others had watched over women at St. Olaf, it was not until Hilleboe became dean that the concerns of women were addressed meaningfully. Former preceptress Georgina Dieson Hegland wrote, “The boys were favored. No doubt about it. Voices continued to be raised against coeducation in the annual church meetings and in the press.” However, “Always, it seems, those connected with the school were in favor of coeducation.”

At first, Hilleboe was daunted by the title. At the second meeting of the National Association of Deans of Women at Columbia University in 1917, she said she felt she “lacked a mature gray head of hair, and I thought I had to develop a stern glance of authority to rate the title St. Olaf gave me.” L. DeAne Lagerquist, in her chapter on Hilleboe in Called to Serve (1999), wrote, “Not yet 30 years old, among the youngest women there and small of stature, she was dubbed ‘the infant dean’ by her colleagues.”

Determined to shed the “green dean” label, Hilleboe enrolled in summer school of the Univ. of Wis. in 1917 in what she called “one of the nation’s first courses for college personnel workers.” She also took training there so she could direct Red Cross work on campus during World War I. In the fall of 1917, the St. Olaf Auxiliary of the Northfield Chapter of the Red Cross was formed and members made 18,000 surgical dressings and did knitting projects. Classes in first aid, nursing and food conservation were provided for the women.

An official Army unit, the Student Army Training Corps (SATC), was instituted in the fall of 1918, combining academic and military training for men. The men’s dorm, Ytterboe Hall, was converted into a barracks. Just hours after the Nov. 11, 1918, Armistice was declared, 15 of the SATC men came down with the Spanish influenza. Hilleboe wrote, “Frantic parents telephoned for their children to come home, but now there were absolute quarantine restrictions. No one was permitted to leave.” Four of the boys died. The siege lifted, but when a girl in Mohn Hall came down with the flu, the students were sent home on Dec. 7 to avoid another siege.

Continuing her own education thanks to a $600 church scholarship, Hilleboe spent the 1921-1922 school year at Columbia University for more training in her field. After completing her M.A., she visited every women’s college in New England.

Hilleboe actively worked to expand women’s opportunities for physical education, which was facilitated by the building of the long-awaited new red brick gymnasium in 1920. (Known as the “women’s gym” when I was a student in the ’60s, it now is the Speech-Theater Building.) Hilleboe also encouraged female participation in student government. She lobbied for a Northfield chapter of the American Association of University Women, which was finally granted in April of 1927 and she then served as president from 1937 to ’39 and 1960 to ’62.

As Dean of Women, one of Hilleboe’s priorities was housing for “my girls.” As a student, Hilleboe had lived in Ladies’ Hall, which had become St. Olaf’s second campus building in 1879. Frugally made from materials salvaged from the original downtown school location, it was finally replaced as a residence for women by Mohn Hall in 1912. (Named for St. Olaf’s first president, Thorbjørn Mohn, this Mohn Hall was torn down in 1967.)

Hilleboe welcomed Ohio Sen. Robert Taft to Agnes Mellby Hall with a 50th birthday cake when he visited St. Olaf on Sept. 7, 1939. Photo courtesy of St. Olaf College Archives.

Hilleboe lived with the 108 women students at Mohn while carrying out a campaign for yet another women’s dorm because, as Hilleboe pointed out, only one-fourth of the more than 400 women students had on-campus housing by 1920. (Her case was buttressed with a 1918 picture called “Mohn Hall Overflowing,” which showed the women crowded on the front porch and leaning out windows.) Meanwhile, the men were occupying the spacious three-story red brick dorm completed in 1901 which had been named for Halvor Ytterboe in 1914, ten years after his death. (This beloved hall, once said to be the “finest men’s college dormitory in Minnesota,” was demolished in 1997.)

In her book, Hilleboe described the 55 years of service of “the heart of the campus,” Mohn Hall. Hilleboe’s office and living quarters were on the first floor. Gatherings were held in the parlors for faculty and students (including her spring party for the senior class and informal cocoa parties), along with “receptions and teas honoring distinguished guests.” In the afternoon faculty members would come to the Mohn cafeteria to what was called the “Round Table” to enjoy an assortment of pies, cakes, cookies and such. Hilleboe wrote, “Everything from the last or next basketball game to problems of world import was subjected to analysis. Jokes and stories added to the fun.” Mohn Hall was also where, in 1937, Hilleboe introduced the system wherein corridors of freshman women had two juniors living with them as counselors to ease their way into college life. (Pamela McDowell, St. Olaf’s director of residence life, told me that this was “one of the first peer mentoring programs in the U.S.” and that the junior counselor system continues today in four first-year dorms.)

Finally, in 1938, the new women’s dormitory built of Faribault limestone was ready to house 180 women. At Hilleboe’s suggestion, it was named for the first female graduate of the college division, Agnes Mellby (Class of 1893) who became a preceptress and teacher at St. Olaf. (The college division was added to the academy work in 1886.)

In Dear Old Hill (1992), St. Olaf’s historian Joseph Shaw recounted how Hilleboe had raised nearly $2,000 from alumnae through $1 contributions toward the cost of having wooden paneling in the foyer and lounge of Agnes Mellby Hall. When the building committee felt the need to cut costs and eliminate the paneling, Hilleboe firmly insisted that she would “refund to the donors the money so far received if it were not used for the purpose requested and given.” Shaw concluded, “Since that time, many appreciative comments have been heard from both students and visitors about the beauty of the red oak paneling, thus firmly vindicating Hilleboe’s firm stand.”

Hilleboe played hostess to many distinguished college visitors over the years but she wrote that the “most exciting of all” was the visit from Norway’s Crown Prince Olav and Crown Princess Martha on May 7-8, 1939. Hilleboe not only gave up her first floor living quarters at Agnes Mellby Hall to the guests, but all the first floor residents moved to the second floor. Following a concert by the St. Olaf Choir at the gym, a gala reception was held in the Agnes Mellby living room. The next morning, the seniors of the home economics department prepared a breakfast of grapefruit, toast, bacon, eggs and coffee – along with Northfield’s Malt-O-Meal cereal, which Hilleboe described as a “novelty” for the royals. The awarding to the prince of an honorary doctor’s degree in the gym was upstaged by an accident when professor C.A. Mellby toppled backward in his chair off the edge of the platform. The chair was caught backstage and deftly pushed back into place, with the professor calmly polishing his glasses as the audience cheered.

World War II brought disruptions as men left for military service and as women students tripled up at Mellby because Mohn and Ytterboe dorms were being used to house cadets of the Naval Pre-Flight Training School. Groups of 200 spent three months at a time on campus before being reassigned. Hilleboe sent out long, mimeographed letters with personal comments penciled in to military personnel connected to St. Olaf during the war. (About 1930, she had also made it her “project” to send personal birthday greetings to 1,300 women who had graduated since she became dean.) With the return of civilian life after the war in 1946, freshmen made up 749 of the student body of 1,660. Hilleboe said the college committed itself to “do our utmost to qualify our students for making their contribution to the rebuilding of our shattered and chaotic world.”

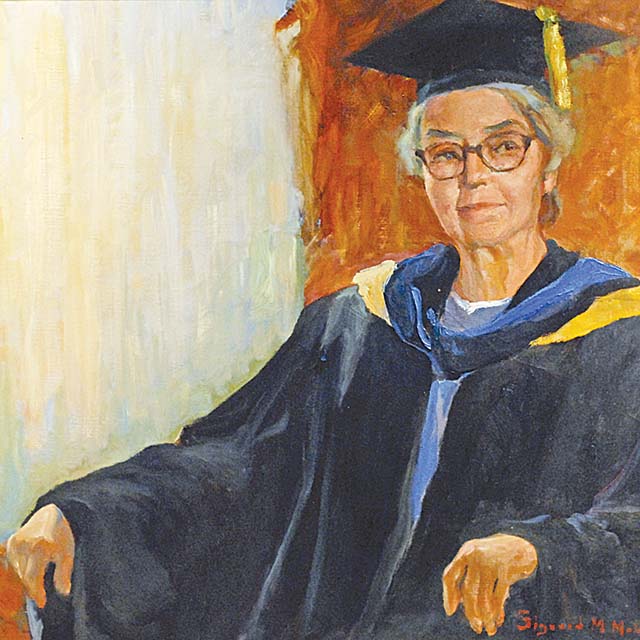

On June 6, 1949, Augustana College in Sioux Falls awarded Hilleboe an honorary doctor of laws degree. In October, St. Olaf surprised her with a recognition party, presenting her with money “to be used for the purchase of a scholastic gown to wear with her Doctor of Laws hood.”

Hilleboe’s next honor came on Homecoming, Oct. 27, 1951, when a new Norman Gothic limestone dorm housing 110 women was dedicated as Hilleboe Hall. She lived here until the next year when she moved to a house of her own on Lincoln Lane, a quarter mile from campus. (A wing adjacent to this hall, Agnes Kittelsby Hall, was dedicated in October of 1957, with the Agnes Larson women’s tower dorm added in 1964.)

Hilleboe’s 80th birthday and publication of her book Manitou Analecta were celebrated on March 18, 1968, at Fairview Hospital in Minneapolis where she was recovering from a broken hip. Standing behind Hilleboe was Sidney Rand, President of St. Olaf. Photo courtesy of St. Olaf College Archives.

Hilleboe retired as dean after 43 years at the end of the 1957-58 school year, though she continued to teach some courses in Latin. At the time of her retirement, she said her personal reward had been “the rare chance to grow up again each year” with incoming freshmen, who “are just as uncertain and bewildered as I was when I came here.” Among stories recounted in the college news bureau release was the day a “tear-drenched freshman girl” stumbled into her office sobbing, “I want to go home” because her pet hamster had died and the family was “saving it in the refrigerator until she could get there.” (She was permitted to go.) In a Minneapolis Star story on March 20, 1968, Hilleboe told her method of first matching roommates by height and weight to avoid self-consciousness because her first year she “wound up putting a girl who was less than five feet with one who was almost seven feet tall.”

Hilleboe died on Aug. 20, 1976, at the age of 88. Her family put a message of appreciation on the funeral folder, starting with words from an East Indian poet: “Death is not extinguishing the light. It is turning out the lamp, because the dawn has come.” Despite pain in her last years, “She was not only happy in her faith, she was earthly-happy too, because countless friends the wide world over shared their lives and times with her” through letters and visits. An organist “launched Gertrude’s final Christmas with beautiful music by playing a mini-concert for her via phone, all the way from the West coast.” Gertrude had attained her “special personal ambition the last years of her life” by living until the Centennial year (1974) of St. Olaf. “And then those grand people on the Hill made it a star-spangled year for her by making it possible for her to attend a half dozen of the topflight events. Physically she attended in a wheelchair. Emotionally she was raised to tiptoe excitement with the thrill of it all.”

Shaw wrote in the History of St. Olaf College (1974) that Hilleboe’s effectiveness was “based on Christian ideals, scrupulous fairness and mature wisdom. Her standards and expectations seemed impossibly high to many, colleagues as well as students, but her unassailable motives and powerful influence left little to criticize. Moreover, she knew the women students by name and showed a personal interest in each one.” Shaw concluded, “Miss Hilleboe will long be honored as one of the most memorable builders of St. Olaf College. Her record of dedicated service and inspiring leadership corroborated what President Vigness was often heard to say, ‘One of the best things I did was to get Miss Hilleboe here.’”

Thanks to St. Olaf College Associate Archivist Jeff Sauve and Dr. Joseph M. Shaw for their assistance with this story. (The Shaw-Olson Center for College History at the Archives is named for Shaw and former archivist Joan Olson.)

Do Red Dresses Incite Male Passions?

Hilleboe’s concern for female students included development of character and responsibility as well as close attention to their dress and social behavior (for such attention not all were grateful).

~ L. DeAne Lagerquist

Anecdotes abound about such attention from St. Olaf’s longtime Dean of Women. From the 1940s: I always changed the direction I was walking on campus to avoid Gertrude Hilleboe who yelled at me for wearing knee highs and skirts shorter than she liked; If you did not wear a hat to church, Miss Hilleboe called us to her office on Monday morning; Though our room in Agnes Mellby Hall was far away as possible from the room of Gertrude Hilleboe, she found her way to us having a party after hours. All she said was “My senior girls!;” Advice from Dean Hilleboe at orientation: “Always use a catalogue if you must sit on a boy’s lap in the car.”

St. Olaf historian and Professor Emeritus of Religion Joseph M. Shaw (Class of 1949) has heard such stories about Dean Hilleboe, including her supposed rule, “Girls should not wear red dresses lest male passions be aroused thereby.” He had the opportunity, while working on a centennial history of the college, to ask her directly about this rule and the catalogue (or Minneapolis phonebook, depending on the teller) on the lap. She denied the stories. In fact, having heard the tale about the red dress years ago from junior counselors, she made it a point to wear a bright red dress at the next dean’s meeting. Shaw discovered that his firsthand account did not sway his classmates who were telling Hilleboe stories at a reunion gathering some years ago.

Shaw told me he would like to avoid turning Hilleboe into a “caricature.” Shaw and I agreed that most of the women accepted the rules of the day which Hilleboe enforced, college rules which started changing in the 1960s. Shaw said she understood the role of discipline as part of “building character, instilling solid values that would serve the students in the future.”

Shaw also feels she rendered a “social etiquette” service, teaching “how to act in adult society” with the coffee hours, teas and other social gatherings she held at Agnes Mellby Hall. She was in this way following the path of her revered uncle Halvor Ytterboe who “helped young people from small towns and the country to learn some social graces.”

In that regard, let me recommend the book Etiquette 101 by Halvor T. Ytterboe, compiled and edited by Jeff M. Sauve and published by the St. Olaf Archives in 2011. Available at the college bookstore, it includes 101 “timeless, albeit somewhat antiquated” rules for students in the late 1880s.

Ytterboe advises, “Do not dress more costly than you can afford.” He does not, however, say anything about red dresses.