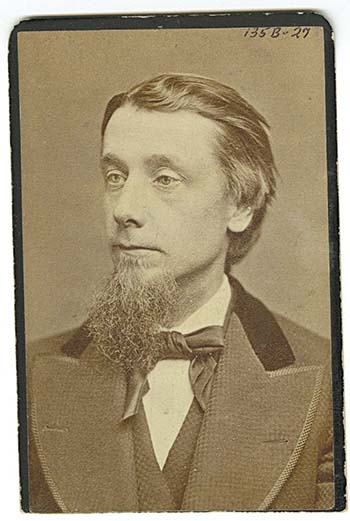

The name Thomas Scott Buckham is most likely associated today with the library bearing his name at 11 Division St. E in Faribault. But during his long lifetime (1835-1928), Buckham was widely respected as a judge who was (in the words of Phyllis Schuster in a Faribault Daily News story of July 19, 1980) “a learned man who delighted in classical scholarship, who cared little for material possessions, with the exception of books, and lived a frugal, somewhat eccentric life.” Part of Buckham’s eccentricity may have come from his unusual marriage to his wife, Anna, who gave Faribault its impressive moderne/Art Deco library in this month of July, 83 years ago.

Buckham has a connection to Northfield, too, which I discovered while doing research for a book on Northfield’s oldest building, the Lyceum, that I wrote for the Northfield Historical Society in 2010. Buckham had been the first vice president of the Lyceum Society, whose aim was to establish a “reading room, circulating library and debating society.” The group first met on Oct. 1, 1856, in the new schoolhouse before town founder John North built the Lyceum Building the next year.

Buckham’s name popped up often in the minutes (which have been preserved at the Rice County Historical Society in Faribault), including this entry from January of 1857 about a debate on the topic “that territorial extension is the true policy of our government”: “Thomas Buckham advanced and rebutted his own arguments with equal favor and effect.” I had written in my book that his effectiveness as a debater “stood him in good stead in Rice County District Court when he, as a Faribault attorney, represented the Younger Brothers after their capture in Madelia after their participation in the September 7, 1876, Northfield Bank Raid.” (Bob, Jim and Cole Younger pled guilty and thus avoided capital punishment.)

Thomas Scott Buckham was a native of Chelsea, Vermont, who graduated at the top of his class at the Univ. of Vermont in 1855. He then taught Greek for one year at Mexico (N.Y.) Academy where he fell in love with 17-year-old music teacher Anna Mallary. Her parents, Lyman and Theresa Mallary of Brooklyn, N.Y., were opposed to the romance, which nonetheless proceeded via letters when Buckham heeded the motto of the 19th century, “Go west, young man!” His father, James Buckham (a minister from Scotland in Chelsea) had passed to his son not only his love of Greek classics but a stake of gold valued at several hundred dollars. Buckham made his way with a school friend to the newly founded town of Northfield in the territory of Minnesota in 1856 and worked as a bookkeeper at Ames Mill.

But it was not long before the intelligent young man moved to Faribault to “read law” with George Washington Batchelder and soon entered into a legal partnership with him. Buckham was elected the county’s prosecuting attorney and served as Rice County’s first superintendent of schools.

On Thanksgiving Day, Nov. 29, 1866, after ten years of correspondence and with Buckham having established himself, he and Anna were wed in Brooklyn and she consented at last to come out to the new state of Minnesota. After Thomas and Anna were deceased, Anzina Chase Batchelder (wife of Charles Batchelder, George W. Batchelder’s son who had also gone into law practice with his father) felt free to give her “personal reminiscences” of their unique union in a paper read to the Rice County Historical Society on Nov. 5, 1941.

Alzina Batchelder said Anna went west “in spite of the forebodings and lamentations of her friends and relatives.” However, “a promise was exacted that she could come back often for long visits, as her father and mother were still unreconciled to her marriage to one so completely out of the world and she also had an invalid sister who was inconsolable over her loss.” Alzina sympathized with Anna, saying that anyone who knew her, “feminine to a degree, with her love of the finest in music, art and people, with her background of life in the best modern tradition of her time, in the up to date city of Brooklyn, can understand her reluctance to leave, even for love, her home with its security and comfort, for one in the far west…It took courage, and a sort of defiance of fate, to decide to cut loose from all she loved, and encounter she knew not what. Who can blame her for hesitating?”

The Buckhams lived in large, pleasant, furnished rooms in a boarding house which was then considered a “rather genteel way of life,” according to Alzina’s account. They entertained often, Anna was the first vice president of the Ladies Literary Club (forerunner of what was next called the Monday Club) and the couple became charter members of the Travellers Club. But, said Alzina, “Mrs. Buckham was a true lady of the old school, and as such, did not take much interest in housework or cooking for ladies, while such heavy work as washing, ironing or sweeping was supposed to be done only by servants.” The couple had no children, after the birth of a stillborn daughter in 1869, but the Buckhams were said to have shown much affection for the children of others, including inviting them to maple sugaring parties.

Thomas Buckham’s responsibilities increased in the 1870s as Buckham became the second mayor of Faribault and a senator in the state legislature. Then, in 1879, Buckham was appointed judge of the fifth district by Gov. Pillsbury, a position he held until he retired in 1910. Among his other distinctions: Buckham was a regent of the Univ. of Minn., a trustee of Carleton College and President of the Library Board of Faribault when the library was in a city building.

Anna’s long absences from Faribault became more frequent as her parents aged and her sister’s condition worsened. Alzina said that when Judge Buckham was 70 years old he bought (“without much consultation”) a house on First Street South, one of the finest in town, “thinking it would make her more satisfied, to have a home of her own.” However, Alzina continued, “manlike, he had reckoned without considering the effect on his wife. She, never having had the responsibility of a house, found it something of a white elephant for a woman of her age and temperament, to assume care of such a place.” And it “didn’t occur to the Judge that their furniture was quite inadequate, or that curtains and rugs were essential.” Buckham invited friends to visit the house in this unfinished condition, which “was humiliating to the hostess, who liked everything done in conventional fashion and in order, and when she entertained college presidents and persons of importance wanted it done properly. Any woman can understand her feelings.” So when her family summoned her again, “she left the bare pine floors and curtainless windows with a feeling of relief, hoping that before she returned the problem would somehow be solved without her aid. She was over 70 and at that age one sidesteps as many problems as possible.”

This time Anna did not return to Faribault until more than 20 years passed. Alzina said the judge was a lonely man in his last years, “pathetically glad to have his friends drop in and see him.” He never bought a car and was a familiar sight walking around town. Despite their many separations, the couple wrote each other every day and, Alzina said, “He watched as eagerly as any 20 year old lover up to the very last for the daily letter.” He ended each letter to her “With love, sufficient unto the day thereof.” Anna came back to town after being alerted to his deteriorating condition, but just missed his death at the age of 93 on April 22, 1928.

Alzina said she did not remember what year it was when workmen had laid “new parquetry floors in every room of the house,” unmatched in the city, or when Oriental rugs were purchased. But word of his improvements in the house never reached Anna: “She nearly collapsed when she saw what had been done to please her, and many times after she spoke of it with tears in her eyes, and in trembling tones, as she asked why she had not been told.” When Anna learned that he had left an estate of more than three million dollars, she was even more overwhelmed. It was possible he had not even kept track of his fortune, as material comfort for himself was never of interest to him.

By all accounts, Anna enjoyed her newfound wealth, renovating and furnishing the house (a Bradford cabinet from the home is at RCHS), buying a Cadillac (for which she engaged a driver) and purchasing art works. She joined the Monday Club and attended the Congregational Church.

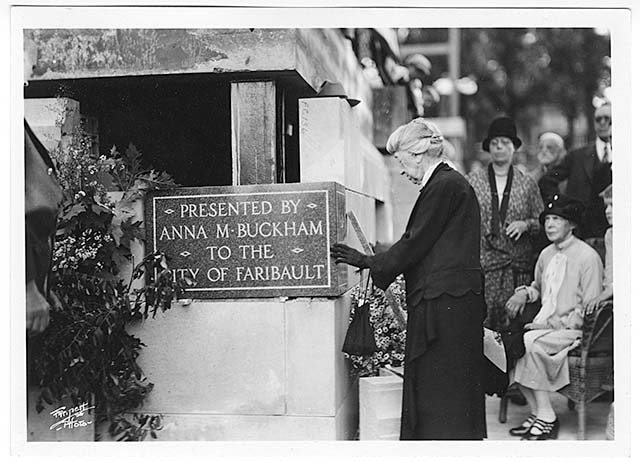

Anna also set about planning the Thomas Scott Buckham Memorial Library on the site of Winkley’s Livery Stable, engaging a nephew, architect Charles Wyman Buckham, to design the building. Murals and a stained glass window were created, which reflected Thomas Buckham’s appreciation of Greek culture. (See sidebar on next page.) The cornerstone was laid on Sept. 22, 1929, and she presented the library to Faribault on July 20, 1930. She was said to have visited the library frequently thereafter.

The Rice County Historical Society, formed in 1926, has a special connection to the story of the Buckhams because, in 1928, RCHS approached Anna to ask her if she would consider having a room in the proposed library for a museum, which would include her husband’s papers and other collections. She agreed and the RCHS museum was housed there from 1930 until a new museum was opened at the former county highway building at the east end of the Rice County Fairgrounds during the fair in July of 1978.

Anna died on Feb. 27, 1935, at the age of 96. In a rather strange twist, she left directions that her husband’s cremated remains should be taken from the Buckham family plot in Vermont to be interred beside her in her family’s plot in Brooklyn. This bothered some people who felt the judge should have been buried in Faribault in the first place. Nevertheless, perhaps being in eternal rest next to Anna would have been the judge’s desire after so many years apart. And though Judge Buckham’s remains are in a grave in New York, surely his spirit lives on in the Thomas Scott Buckham Memorial Library that Anna gave as an enduring gift to the town he called home for so many years.

Thanks to Susan Garwood (Executive Director of the Rice County Historical Society), Jeff Jarvis (of Faribault Parks & Recreation Dept.) and Delane James (Director of the Buckham Memorial Library) for their assistance with this story.

The Thomas Scott Buckham Memorial Library

A noted Vermont architect working out of New York City, an acknowledged stained glass master from Boston at the height of his career and a young professor from Scotland who built up the art department at Carleton College contributed their considerable talents to the Thomas Scott Buckham Memorial Library. This Moderne/Art Deco style building, which cost $239,000 and was made up of 5,224 Kasota limestone blocks, has served the city of Faribault well since 1930.

Buckham’s widow Anna, who financed the library, knew at once who should be the architect: Charles Buckham, the youngest son of Thomas Buckham’s brother Matthew (who was the 26th president of the Univ. of Vermont). Like his father, Matthew, and Uncle Thomas, Charles Buckham was also a graduate of the Univ. of Vermont. Charles had made a name for himself in New York after post-graduate work at Columbia University. Considered a pioneer in NYC apartment-building, he also patented an interlocking floor type of library construction – an arrangement of library stacks in which every reading room opened into the stacks, which was part of the Faribault library design originally. He also was noted for the use of ramps rather than stairways in public school construction and for multi-floor parking garages.

Visitors to the library cannot fail to notice the large stained glass window in the center of the building. Anna Buckham spared no expense in hiring stained glass master Charles J. Connick of Boston to create what Connick called his “effort to express in light and color the spirit of Greek tradition.” The left panel represents Athens, “the climax of intellectual attainment,” with Socrates embodying Greek intelligence and Pericles as “the flower of Athenian statesmanship and the supreme orator.” The right panel is devoted to the “bravery and military genius” of Sparta and the center panel presents Homer and Aeschylus, typifying “the perfect flowering of the Greek genius.” Five figures from Greek mythology are in the arch at the top, with Nike, Victory, at the very top of the window, “symbolizing the lofty achievement of the Greek spirit.” Connick wrote that this window “should sing in the light, as a symphonic poem might sing through the voices of many instruments, to remind us that there are still ‘Regions of undiscovered loveliness that may teach us what real beauty is.’” Connick would go on to design the famous rose windows of the cathedrals of St. John the Divine and St. Patrick’s in New York City. Upon his death in 1945, The New York Times said Connick was “considered the world’s greatest artisan on stained windows.”

Four Greek murals on the walls of the Great Hall on the second floor of the library depict scenes from Olympia, Athens, Sparta and Delphi, painted by Alfred J. Hyslop. A graduate of the College of Art of the University of Edinburgh, Hyslop came to Carleton College in 1923 as the first full-time art teacher. He became department head in 1935 and taught until 1963, earning many honors along the way for his artistic accomplishments as he built up the college art department.

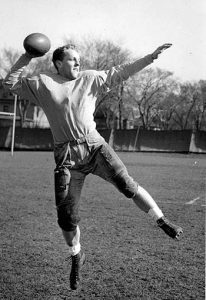

Hyslop wrote, “I have tried in these four panels to interpret the contribution of Greece towards what is beautiful and permanent in the modern world.” He used the principle that grandeur and strength can be realized in “quiet, diurnal scenes which in the end create the loftier moments” than in crises or “spectacular events of a nation’s life.” The scenes, painted in strong, bright colors, are taken from the Age of Pericles, the fourth century B.C., when Greek culture was at its height. The panel devoted to Olympia shows the conclusion of the warriors’ race in the athletic competitions held every four years at the stadium and stands for “physical prowess,” according to the artist. The mural of Athens represents “art and philosophy,” as shown by a teacher of philosophy instructing his followers, with the Parthenon in the background. Sparta stands for courage, with a scene of a morning assembly at the military academy as a young recruit is introduced to his commanding officer. Delphi stands for worship, as a penitent offers a goat as a sacrifice and worshippers proceed from a temple.

When the cornerstone of the library was laid in 1929, Donald J. Cowling (the president of Carleton College and a close friend of Thomas Buckham) told the gathering, “Generations to come will build upon the foundations we lay, great centers of human culture and institutions for the enlargement and enrichment of life everywhere.” He concluded, “The building will stand throughout the years as a memorial to a representative and distinguished citizen of Faribault and of Minnesota, and as a monument to the ideals of religion and learning which he embodied.”