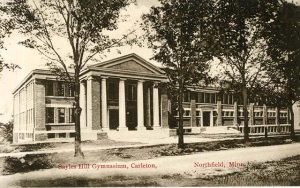

It all started with an extraordinary invitation by Minnesota Twins’ owner Cal Griffith 45 years ago. Sid Freeman, owner of a Northfield men’s store the Hub and president of Skeffington’s, a chain of formal men’s wear shops, told his friend Griffith that his alma mater Carleton College was celebrating its centennial. Griffith then invited the college students, faculty and staff to be his guests at a Twins evening game against the Chicago White Sox on May 22, 1967. Carleton President John Nason wrote to Centennial organizer George Soule on April 25, 1967, that “Sid Freeman and I lunched with Cal Griffith yesterday at the stadium and Cal could not have been more hospitable or more generous,” offering tickets in the grandstand behind first base and stretching out toward right field. Tickets were provided for 1,254 students, faculty and staff who made it to the game at Metropolitan Stadium (current site of Mall of America in Bloomington) by way of 23 buses and many cars.

The always inventive Carleton students had come up with other ways to celebrate the 100-year history of their college, from a Centennial panty raid (details are “scanty” but the aim seemed to be acquiring 100 panties from a raid on women’s dorms) to a 100-inning softball game on May 16. The game, which started at 6 a.m. and lasted nine hours, involved 10 seniors per team, each playing 10 innings at 10 fielding positions. The game ended with the fitting centenary score of Sots 100, Dirty Old Men 81. (Carleton still plays a marathon softball game each year, one inning for every year since its founding, named after a popular Rotblatt softball league of days of yore. This year’s 146-inning game will be played on May 26.)

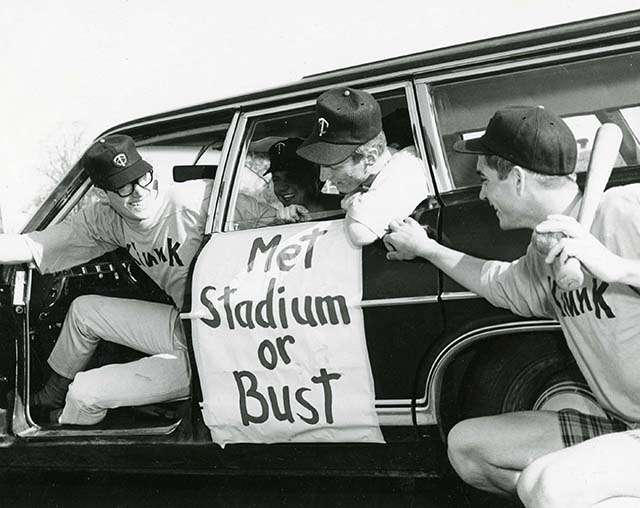

Mac Welles, ’67, recalled that he was in the outfield in the midst of the centennial marathon game when Jane Koelges (director of the Carleton College News Bureau) came out to see him with a reporter from the Twin Cities. Koelges talked about the invitation from Cal Griffith and asked him, “What can we do to make this even more exciting and newsworthy?” Welles told me, “We were brainstorming and I have no idea how I came up with the idea but I suggested batting a ball from Northfield to the Met. Then I talked it over with the baseball guys and in my dorm, we got the support of the food service to provide snacks and got two college cars.” When the highway patrol threatened arrest if the stunt was carried out along the freeway, a route was mapped out along the shoulders of Minnesota highways 3, 49, 55 and 13 and along Cedar Avenue in Bloomington.

Participants were Welles of Duluth, Marc Mosiman of Minnetonka, Ted Lutz of Richfield, Hal Arkes of Chicago, Gary Sundem of Minnetonka, Bob Carlson of Pine City, George Jacobson of Capitola, California, and drivers Ray Borens of Morris and Rick Roland of Minneapolis.

The Minneapolis Tribune and the St. Paul Pioneer Press wrote about the “batty” adventure, both before and after the event. The Pioneer Press of May 21 said, “Natural obstacles will not be bypassed but the hitters will attempt to drive the ball across such things as creaks and ponds. Because this may mean the loss of a ball or two, the teams are taking ten baseballs along with them.” The article concluded with a quote from an unnamed senior: “This may sound silly, but at least we won’t celebrate the end of school by running across the campus naked.”

At 8:15 on May 22 the stunt began. Lutz described to me how the venture of bats and balls and gloves took place: “Station wagon number one would spread 4-5 guys along the route while station wagon number two would spread the others up ahead. Group one would fungo the ball ahead to each other, get back in the vehicle, and leap frog group two. And so it went for 10-11 hours. As you can imagine, we had guys retrieving the ball from cow pens, farm machinery, etc. We also probably gave some motorists near heart attacks while fungoing through small towns.” Lutz said people were “very nice throughout the whole day – after all, this was Minnesota.” Arkes remembered, “While going through one micro-dot town en route to the Cities we were amazed to find a group of ladies who gave us a warm, official, municipal welcome with lemonade and cookies. It may have been the biggest event in the town in decades.”

On May 23, the Pioneer Press printed two photos of the “batty group with the elongated outfield,” which covered a distance “as the ball flies of 41 miles.” Sundem provided the paper with this “box score”: “One lost baseball (it disappeared while crossing the Minnesota River) and two taken out of the game for cut seams and water logging.” (Lutz told me he “failed to hit it over the river in my first try.”) Sundem said one hit went into a culvert and was rescued by Welles. One building, near highway 13 and three or four parked cars were hit but “no damage.” Also hit: “Ten to a dozen highway signs – speed limit, curve, stop signs and at least one commercial sign.” Sundem said, “We managed to spray the ball around a bit, especially at first.” He estimated they averaged 40 hits a mile, with spacing at about 200-foot intervals.

Sundem told the Pioneer Press that “Everybody along the way was real inquisitive, but not many cars stopped to ask questions.” He added, “Traffic wasn’t really too bad at all until Cedar Avenue when we ran into rush-hour and got a few dirty looks. We hit grounders a lot then.” The article concluded, “The movable slugfest ended at about 5:30 p.m. when the sluggers drove their play into the park through the center field gate.”

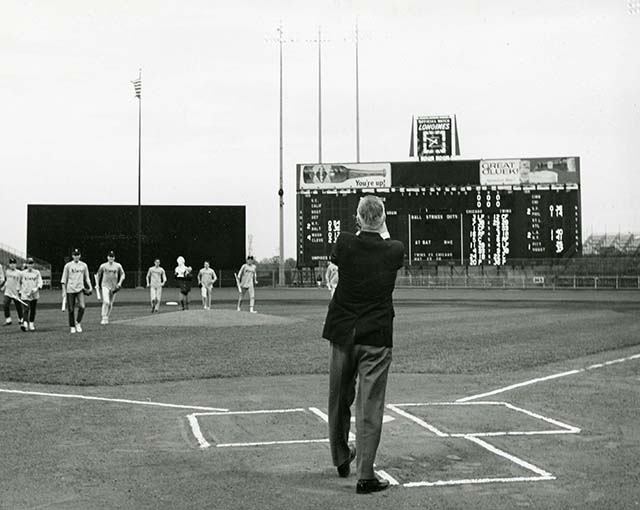

Within minutes after arriving, “the group was engrossed in watching the Twins’ batting practice.”

Sundem told me, “My personal recollection is that the trip went much more quickly than expected with very few errant hits. The participants were a combination of players from the varsity baseball team and players from the college’s Rotblatt softball league. The countryside we went through was sparsely populated until we crossed the Minnesota River and there was little traffic. Today the trek would be much more difficult, lined with shopping malls and stoplights and loads of traffic much of the way.”

Lutz remembered, “We arrived in the vicinity of the Met at rush hour; this fact presented a few significant hurdles to completing our mission. However, we made it – totally wiped out, of course – and I do recall the Twins hosted a very nice buffet for us up in the Stadium club.”

The pre-game ceremony began with Cal Griffith introducing President Nason to the crowd. Nason thanked Griffith for the invitation honoring the college and pointed out that Carleton’s origin preceded the birth of baseball by two years. Arkes recounted what happened next: “At an appointed time, the grounds crew opened the gate at center field. We then continued the fungo-a-thon from the gate to the pitcher’s mound, where Mac Welles gently and accurately hit the ball to President Nason, who was standing on home plate. The Prez exhibited good hands, catching the ball on the fly.” Welles added a postscript. After President Nason caught the ball, Welles started running to home plate and “he threw it back to me and hit me right in the stomach. I didn’t expect that!”

Then came a presentation of gifts from the college. Eric Janus, Carleton ’68, told me, “As president of the Carleton Student Association, I was assigned to present the Carleton Chair to Calvin Griffith.” By coincidence, Janus (from Bethesda, Maryland) had been a fan of the Washington Senators, the team which Griffith moved to Minnesota in 1961. There was an even bigger coincidence involving the presentation of a Carleton Captain’s chair to Twins’ manager Sam Mele by Bardwell Smith, who had been chosen as Carleton’s new Dean of the College. Mele had played baseball for Yale for Red Rolfe as a Navy V-12 trainee in 1943-44. When Mele was a senior, Smith was his freshman replacement in right field. Smith (who still lives in Northfield) told me his words were, “I’m giving this Carleton chair to you because, as you remember, I was a substitute for you in right field at Yale and I sat on the bench game after game, but when our team got many runs ahead, then I was put in your place. So this is a chance for you to sit in this chair as I sat on the bench.”

Also saying a few words at the ceremony was Twins pitching coach Early Wynn, who had pitched for the Washington Senators, Cleveland Indians and Chicago White Sox. Wynn had won his 300th game with the Indians on July 13, 1963, and was pitching coach 1967-69 for the Twins. He was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1972. (It is part of baseball lore that Wynn claimed he would throw at his own grandmother if she crowded the plate: “I’d have to. My grandma could really hit the curveball.” Twins slugger Rod Carew even said Wynn would “knock you down in batting practice.” )

As for the game itself, Hal Arkes remembered that the Twins beat the White Sox 8-7. “The Twins won, thanks to some poor relief pitching by White Sox hurler Bob Locker. Twins relief pitcher Al Worthington held the White Sox scoreless over the last two or three innings.” Perhaps not all the Northfield contingent was cheering for the Twins, despite Griffith’s largesse. The Carleton News Bureau reported that of the 1200 guests, “nearly 200 are residents of Chicagoland.”

There is a copy of a letter in the Carleton Archives to the Twins public relations director about what happened when the hitters returned to the dining room for equipment after the game: “They had cokes and cookies with Cal Griffith. It seems that he was having a solitary snack and invited them to join him. Mr. Griffith has at least ten new admirers who are singing his praises to the sky.” Jane Koelges wrote that “we have a mighty sweet and vulnerable crop” at Carleton, “in spite of all that’s said and done about the way-out college students of today.” And these Carleton students have “managed to worm their way into a lot of hearts around here.”

A few days after the May 22nd game, a woman from St. Cloud wrote a letter to the editor of the Minneapolis Tribune about Carleton’s participation. She asked, “Why, oh why did they let their long-haired, beatnik-looking president of the student body make the presentations?…It certainly left a very undesirable impression of this fine college among many of the fans witnessing the presentations.” Three subsequent letters to the editor from Northfield were printed in defense of Eric Janus. Robert Hofmann declared, “Our student leader is not a beatnik. Beatniks smoke, drink and swear. Eric doesn’t.” He said Eric’s hair and bushy mustache were grown “with the sincere intention” of honoring the centennial baseball pilgrimage. Janus, who provided a copy of these letters to me, said that in reality he had gotten a haircut for this event and he may not have been the paragon of virtues portrayed by Hofmann. But Janus seems to have made his way successfully in the world. He is now president and dean of William Mitchell College of Law in St. Paul.

I talked to Bardwell Smith about those days in the ’60s when long hair was an issue with some people. He remembered the comment of a barber: “You used to be able to tell the difference between Oles and Carls, as the Carls used to have longer hair, but in a year or two all the college kids had long hair, real scruffy-like, and lots of beards. Soon, they all looked alike.”

Smith had forged a close relationship with students of this era, from his years teaching religion at Carleton from 1960-67 and five subsequent years as Dean of the College. He noted that the times were serious, “filled with energy and promise,” with a belief that responsible change was possible. Students “combined seriousness with a capacity for the whimsical,” as shown in some of the centennial celebrations.

When the Carleton class of 1967 gathers for its 45th reunion next month, you can be sure many of the class members will be reminiscing about the Rotblatt softball league, the 100-inning game and that trip to Metropolitan Stadium in Bloomington, whether they rode the bus or batted a ball 41 miles to get there.

Photos courtesy of Carleton College Archives.