Early in the 20th century, Carleton College students eagerly awaited an ice cream party which celebrated the advent of spring after yet another long Minnesota winter. In 1909, a more elaborate event was announced in the Carletonia of May 20: “Instead of the customary ice cream social a May day festival will be held on the east lawn of Gridley May 22 under the auspices of the Y.M. and Y.W.C.A.” A special program would include marches, a Maypole dance and singing of the Glee Club. “An interesting feature will be the crowning of the May Queen, Miss Winifred Baker…Besides all this ice cream will be served and all can be had for only 15 cents. Better come.” A spring tradition was established and then carried out by the women of Carleton for more than half a century.

In 1910, inclement weather caused the fete to be held indoors, with Margaret Birch chosen as Queen by YWCA members from three senior candidates. In 1911, it was held once more behind Gridley, the woman’s dorm: “The background of trees, the Maize and Blue streamers from the pole, the pretty hoops in the same colors and the white dresses worn by the girls, together with the graceful movements of the pretty Maypole dance, made the scene a very beautiful one,” according to the Carletonia of May 23. The young ladies then put on “a very clever presentation of As You Like It.” In 1912, six members of Edna Lowe’s advanced oratory class presented Ingomar, the Barbarian with 24 girls performing a Venetian dance between acts. In 1913, more than 300 people attended an event featuring a Japanese operetta “of artistic merit,” along with the crowning of the May Queen and Maypole dance (with a professor’s dog participating in the dance, going “round and round the pole vainly trying to fall into step”).

The Carletonia of May 26, 1914, reported that as spectators either crowded around a candy booth or awaited the ceremony on Gridley lawn, “Here or there one heard snatches of philosophical discussions of the ‘moral and aesthetic uplift of the May Fete’ but the burden of the conversation seemed to be concerned with the identity of the fair May Queen.” The orchestra then “struck the notes of a triumphal march” and the Girls’ Glee Club sang a May Day song as the Queen received a crown of lilacs and was honored by dances and with the operetta Snow White, presented “realistically” amid the pines and elms. “The fairies appealed to the audience with their sprightliness and grace; the dwarfs gained the laughter of all with their grotesque humor.” The net receipts of $75 went into a YWCA fund.

Student-written themes and Greek and Roman classics predominated in the first two decades of May Fete. In 1918, after Lyman Memorial Lakes had been created on campus, seats were set up on the south shore and, despite threatening rain, a large crowd watched the prince in Prince of Spring make his entrance paddling a canoe. Receipts of more than $200 went to the Red Cross.

By the 1920s, according to Carleton: The First Century (by Leal Headley and Merrill Jarchow, 1966), May Fete was “considered the most beautiful and impressive event of its kind in the northwest.” It was “anticipated with excitement and pleasure by most students” and “attracted more outside visitors to the College than any other event of the year.” In 1921, “the island in the lower Lyman lake was chosen for a stage setting and a rustic bridge was built for those taking part to cross over. This area, together with the hillside rising from the shore, made a splendid amphitheater in which May Fetes provided memorable experiences annually for the next 40 years.” Also in 1921, the senior candidates for May Queen were voted on by all the women on campus instead of just by those in the YWCA. (The next decade would see some rumblings of discontent about men having no say.)

For Sappho, the Greek Poetess in 1922, a 12-foot cliff was constructed on the island for the leap which Sappho took in sorrow when spurned by the boatman. The spectacle was viewed by 3,000 people under ideal weather conditions. Venetian Carnival in 1923 was highlighted by a regatta of 15 gondolas on the lakes and dances involving a fountain, dragonflies and 150 colorful balloons. Proceeds from the 1923 May Fete and subsequent years went to a fund for a Women’s New Gymnasium for which, according to the Carletonian of May 9, plans were nearing completion. As it turned out, it would take 42 more years before the Elizabeth Cowling Recreation Center for Women was opened in 1965.

Popular as the May Fetes were, they were a source of some ridicule, particularly among the males on campus. In 1916, a student gathering at Sayles-Hill Gym was entertained by a “masculine interpretation of the May Fete” which “provoked much laughter.” Roger Dunn, in a Carletonian column entitled “Sophistication” on March 22, 1924, wrote in free verse in capital letters:

WE DON’T MIND MAY FETES/ BUT WHY IN THE NAME OF HEAVEN/MUST THEY ALWAYS ATTEMPT TO IMITATE BIRDS, LEAVES, BEES,/SNOWFLAKES AND GNOMES?/ WE’RE BIG BOYS AND GIRLS NOW.

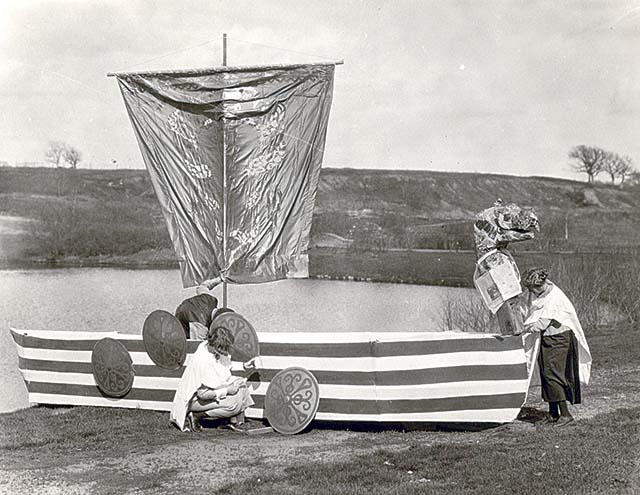

The spring of 1924 brought one of the most spectacular and elaborate pageants of all, Sigurd the Volsung, about Norse gods. Yes, also featured were the sources of Roger Dunn’s plaintive poem: birds, “nimble elves turning cartwheels” and a snowflake ballet of 125 dancers, together with green-haired mermaids, a chariot drawn by two goats and a Viking boat, “historically accurate in every detail” with a carved dragon’s head on the prow and dragon’s tail stern.

Almost all Carleton women were involved in some way in this 1924 pageant, with faculty members contributing talents as well. Jimmy Gillette, who led the Carleton Symphonic Band to nationally recognized heights during his tenure 1923-1938, put together and directed an outstanding 60-piece orchestra to furnish the demanding music of Wagner (The Valkyrie) and other composers on a special new stage. The Northfield News of May 23, 1924, said: “This orchestra will be composed of 30 members of the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra, which has just returned from its successful spring tour, members of the Carleton College Concert orchestra, and members of the Carleton and St. Olaf bands.” On May 30, the newspaper estimated the attendance at 4,000, “in spite of cold day and threatening rain.” Mr. and Mrs. George Lyman of California, donors of the lakes, were among those present.

In 1925, The Enchanted Flute about a princess seeking adventures in fairyland was presented on yet another cold day, provoking a student to write “Just A Word for the Weaker Sex” in the Carletonian on May 27: “Some hundred girls just finished dancing barefooted on damp grass while freezing mists drove over their sheer costumes” during the “female frolic.” Although the dances and fairy pantomime are “lost no doubt on grosser beings,” they are “a source of delight to those with the soul to love the beautifully imaginative” and the dancing requires “as much muscular skill as does the catching of a wet pigskin.”

The weather was ideal for Ki-Tchi-Mak-Wa in 1926. This pageant was a romance between an Indian princess and a warrior, with a village set up on a Lyman Lakes island with teepees, several totem poles (one 18-feet tall), council fires and “real Indian tom-toms.” Almost 300 Carleton women took part, along with local children. Student Evelyn Lambert, of Indian parentage from Mission, S.Dak., played the part of an Indian chief. Professors Gillette and Frederick Lawrence wrote the musical scores.

A “monstrous, gaudy” 16-foot sea dragon which breathed out talcum powder from its nose was created for the 1928 May Fete about a fisherman’s daughter wooed by a Merman-King, attended by 5,000 people. Noting that the May Fete “adequately fulfills the desire for artistic expression among our co-eds,” a writer in the May 19 Carletonian proposed a scenario for a pageant for men with the title Parlor Snake. Carleton men would portray such characters as Chief Snake, Water Sprite and God’s Gift to Women, with C.J. Hunt (football coach) as dance director. The synopsis ends with: “This has no plot whatsoever, but neither has the other May Fete.”

Starting in 1933, women’s horse shows preceded the pageant (and, in the 1950s, women’s water ballet shows were added to the May Fete weekend). The 1933 Fete theme was Arctic Hay, a burlesque written by sophomore Jean Rice who had transferred from the Univ. of Mich. to live with her sister Peg and brother-in-law Laurence McKinley Gould, newly appointed head of the Department of Geology and Geography. (A noted polar explorer, Gould would go on to lead Carleton as president from 1945-1962.) The April 5 Carletonian said the script was “a combination of acknowledged improbability and detailed accuracy.” The story involved three explorers, Eskimos, a whale, a walrus, a polar bear, a blue goose, flowers – and choruses of snowflakes. Gould defended the inclusion of spring flowers, saying in the paper of May 3 that there were 700 varieties of flowering plants in the Arctic and “I have personally recorded temperatures of 80 degrees above zero in the shade in Greenland in the summer.”

Peter Pan was presented in 1935. Women played major roles, as usual, but local children were also cast and men played pirates. James Hill was singled out as a Captain Hook of great swagger and marvelous voice. By this year, the May Fete had grown to an elaborate performance including the art, dramatics, music and physical education departments. But the Carletonian reminded its readers on May 15, 1935, that the Fete was still primarily “a tribute to the 12 outstanding women of the senior class” who have contributed the most to Carleton, rather than recognizing popularity and beauty as at other colleges.

May Fetes continued during World War II, and the March 4, 1944, Carletonian said that “wartime restrictions will not affect the May Fete very much,” except for simplified costumes and no outside technical assistance. However, “to conserve wartime transportation facilities, only parents living in nearby communities will be invited.”

After the war, in 1946, We Hold These Truths related “the struggle of the American people toward democratic living,” with a story by history professor Lucile Dean and music from professor Henry Woodward. In 1947, a special stage was constructed for Gilbert and Sullivan’s H.M.S. Pinafore. May Fete Island was transformed into a ship with a “genuine barge” on the lake and costumes from New York, from hoop skirts to British Navy sailor suits for men in the cast. Men also appeared in the Moliere-Gounod operetta The Frantic Physician in 1948, the year Northfield’s own Helen Hunter (whose father Stuart Hunter was an English professor at Carleton) was crowned as May Queen.

Local history topics reigned in 1949 with The First 80 Years of Carleton College, honoring the history of the school and its campus traditions; in 1955 with North Star Saga featuring Northfield’s centennial; and 1958 with The River, which focused on the Mississippi, during the centennial of Minnesota statehood.

By the mid-1950s, debate was increasing about the worth of May Fetes. On April 30, 1955, a letter-writer in the Carletonian felt obligated to defend “this most honored and hallowed of all Carleton traditions” and the “honor and pride” felt by the girls in the court who “typify everything for which Carleton stands.” A dance interpretation of the musical Finian’s Rainbow in 1956 was called a “superbly entertaining spectacle” which “will give the fading tradition a veritable shot in the arm.”

A Mere Meanwhile (featuring “Pogo” comic strip characters of Walt Kelly) was celebrated as the 50th annual May Fete in 1957, with former May queens and attendants invited back. Dance numbers included a barbershop quartet of horses, hound-dog sailors and “sexy skunks and ladylike owls at a garden party.” Katherine Werness was crowned Queen out of the 12 seniors selected to represent “the ideal Carleton woman.”

A Jan. 17, 1959, letter to the editor of the Carletonian complained that the designation “ideal Carleton woman” was “vague and pretentious.” He wrote, “We are naïve in even trying to pick 12 women who are Carleton’s moral elite” and dismissed the idea that being a tradition “justifies its continued existence.” That May the May Fete court was introduced at the women’s annual breakfast gathering not as “ideal Carleton women” but as senior women deserving of recognition and “selected on the basis of service, but not necessarily office; that have made tangible contributions in those areas in which they are gifted.” The change came from the May Fete committee. The Pied Piper was the show theme and for the first time admittance was free. The “final modification of the day” was the court’s appearance in “summer formals instead of the traditionally ancient May Fete costumes.”

Although May Queens would still be selected until 1964, the Carletonian headline of Feb. 27, 1960, marked the death knell for May Fete: “May Fete Pageant Dropped, Fine Arts Days Substituted.” In order to stimulate more interest, “particularly among campus males,” the Women’s League would tap Carleton departments for ideas and dispense with the pageant “because of difficulties encountered by the women’s physical education department in finding willing modern dancers.”

An editorial in the May 10, 1961, Carletonian said that 12 senior women had again been chosen for a court but “the right for these 12 women – or any other group similarly chosen – to be honored can be questioned” since the criterion of “service to the college” was “obviously subjective and arbitrary.” The piece concluded, “If there must be a May Fete Court, we suggest it be turned into a plain beauty or popularity contest. Then everyone will know it is meaningless.”

From 1960-1963, after the Queen coronations, short musical programs of folk songs and international dances were given on May Fete Island, including (in 1963) a joint performance by Carleton’s female singers the Keynotes, male Overtones and a St. Olaf folk group. Dolphins’ water shows (such as the Gershwin Swimphony of 1962 at Sayles-Hill pool) and the horse shows continued. An attempt was made by the Women’s League to rejuvenate the “ailing May Fete” in 1964 by turning it into a “Fete des Beaux Arts,” with a film series and other events designed to honor both senior men and women and featuring a co-ed honor court. But the Carletonian headline after the event was stark: “May Fete ‘Beaux Arts’ Plan Criticized for Limited Appeal.” Students said they did not see much honoring of seniors and disliked the offerings.

The attic of Gridley Hall had become the repository for May Fete relics – which was appropriate since May Fetes had their genesis on the verdant east lawn of this venerable girls’ dorm (which dated back to 1883). Pete Schwenger wrote in the Carletonian of April 24, 1963, about a visit he had made here in the company of employee Karen Sanford, “in her bright maid’s uniform.” Mrs. Sanford led the way through stacks of old beds and chairs under a slanting roof. Schwenger took note of an “incongruously Roman object” which stood in a corner.

“This is the chariot they used to use for May Fete,” Mrs. Sanford explained. “It’s been here for 30 years and it was here long before I came… In here is where they keep the old May Fete costumes.” Schwenger wrote, “It seemed that there must be hundreds of costumes there; a forest of them in the darkness, gleaming in purple and rose, bits of tinsel and sequins sparkling here and there.” On the floor he saw other decorations: “silver paper hats now green with tarnish, trophies for now-forgotten honors, boxes filled with – Wow, a garter! And castanets!” The thought popped up: What if there was a fire here?

“Yes,” Mrs. Sanford said, “every time I hear the fire whistle I think of this old building. It’s my second home, you know. I don’t know what I’ll do when they tear it down.” As they stepped into the elevator, she confided, “This is the first time I’ve ever had anyone come up here.”

In 1967, Gridley Hall was torn down and physical mementos of May Fetes disappeared, except for programs and pictures in the Carleton Archives. However, as it was written in Carleton: The First Century, for many years “the reflection of colorful pageantry in the sun-set touched waters of Lyman Lakes, as the last strains of music faded into the distance, made an unforgettable impression on thousands of Carleton students, parents and guests.”

My thanks to Eric Hillemann of the Carleton Archives for his usual exemplary assistance with my research. All photos courtesy of the Carleton College Archives. For more charming photos, go to contentdm.carleton.edu/digital/collection/CCAP.