Dad, why doesn’t Carleton play metric football?”

That question, from Carleton chemistry professor Jerry Mohrig’s teenage son David, sparked a very special and unique “Historic Happening, Northfield Style,” on Sept. 17, 1977: The very first (and last) NCAA-sanctioned metric football game between Carleton and St. Olaf at Carleton’s Laird Stadium.

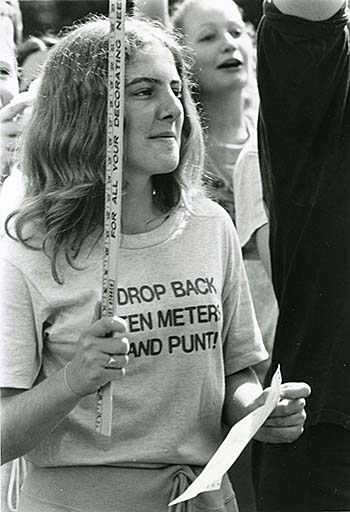

A crowd of more than 9,000 spectators filled Laird Stadium, the largest gathering since Dwight David Eisenhower appeared there during his 1952 presidential campaign. “Cheer liters” led cheers and students carried meter sticks, while wearing T-shirts which proclaimed, “Drop back ten meters and punt.” Special half-time guests included General Ulysses S. Gram, skier Jean-Claude Kilo and baseball legend Harmon Kilogram. The event was covered by national news media (see sidebar). Although St. Olaf won the game, 43-0, the big story was not the outcome but how such a ground-breaking game came about in the first place.

A crowd of more than 9,000 spectators filled Laird Stadium, the largest gathering since Dwight David Eisenhower appeared there during his 1952 presidential campaign. “Cheer liters” led cheers and students carried meter sticks, while wearing T-shirts which proclaimed, “Drop back ten meters and punt.” Special half-time guests included General Ulysses S. Gram, skier Jean-Claude Kilo and baseball legend Harmon Kilogram. The event was covered by national news media (see sidebar). Although St. Olaf won the game, 43-0, the big story was not the outcome but how such a ground-breaking game came about in the first place.

In October of 2008, a panel assembled by the Northfield Historical Society got together to talk about the one and only Liter Bowl. Participants were Jerry Mohrig, instigator of the game; Jack Thurnblad, director of men’s athletics at Carleton from 1960-89; Tom Porter, St. Olaf football coach from 1958-91; Bob Phelps, St. Olaf information director from 1969-84; and Dan Freeman, who announced the game for KYMN radio and who served as moderator for the discussion.

Mohrig explained how his son David, an avid reader of Sports Illustrated, had read an item about how sports such as swimming and track were going metric and perhaps a metric football game should be tried. David asked his father why not Carleton? And the seed was planted. When Jerry Mohrig found himself standing in line next to men’s athletic director Jack Thurnblad during commencement ceremonies in June of 1977, he ran the idea past Thurnblad. Thurnblad told the panel, “I could hardly sleep that night thinking about the ramifications and for me, I couldn’t think of anything negative. It was kind of a win-win situation from the get-go.” Mohrig sent Thurnblad a memo about it, with a copy to Carleton’s acting president Harriet Sheridan. She sent a note to Thurnblad which read, “Jack, make it happen.”

Since Carleton was in the Midwest Conference at that time and St. Olaf was in the MIAC, St. Olaf was the logical opponent for such a game as it would not count in league standings. Thurnblad said he is forever indebted to St. Olaf coach Tom Porter who could have said no. But “gentleman that he is and sportsman that he is, he agreed to the challenge.”

The NCAA did not give an immediate reply to the request for sanction for the game. The main concern, said Thurnblad, was “that the metric statistics of the game would be converted to our uniform way of compiling statistics.” Porter noted that there was a possibility of having a kickoff or punt return of 110 meters, which would mean “exceeding records that were in the books of the regular 100-yard field.” Nevertheless, the NCAA ended up sanctioning the game.

The field had to be realigned with metric markings. The program handed out at the game gave the dimensions of the field: 50 meters wide (54.68 yards) and 100 meters long (109.36 yards) with end zones 10 meters deep (10.94 yards). Player heights were given in centimeters and their weights in kilograms.

First and ten meter drives meant first and almost 11 yards for a first down. Before the game, Porter speculated that the kicking game might become more important on a longer field since you might get the first down less often and have to kick more. During the panel discussion, Porter said, “There was a little more space for the kicking game or the wide game, whether for passing or running. But once you’re on the field and you have the ball, you really didn’t realize any difference between the dimensions of the game” and “the markings were incidental.” Porter did recall “tongue-in-cheek” joshing with the officials before the game that “You probably will earn your paycheck a little bit more today since you’re going to have to run a few yards more.” He noted that the officials were all enthusiastic about being part of this unusual occasion.

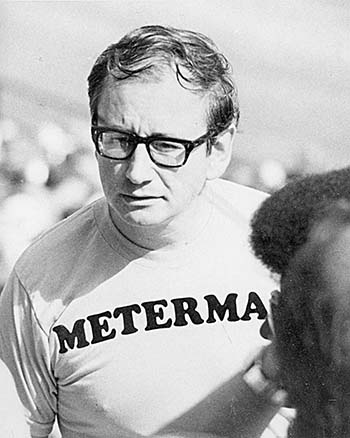

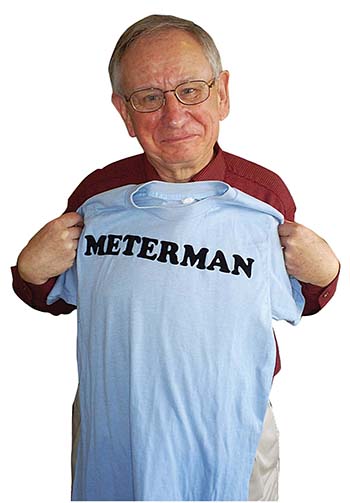

Thurnblad said, “The students just went bananas over it.” Mohrig added, “It’s the only time I can remember in my 36 years at Carleton that students had bonfires before the game. They were really into this.” Mohrig was given a “Meterman” T-shirt and Carleton’s president a “Fearless Liter” T-shirt. A Carleton player said of his Ole opponents, “They’re no differ-ent than we are. They put their pants on one meter at a time.”

Thurnblad said, “The students just went bananas over it.” Mohrig added, “It’s the only time I can remember in my 36 years at Carleton that students had bonfires before the game. They were really into this.” Mohrig was given a “Meterman” T-shirt and Carleton’s president a “Fearless Liter” T-shirt. A Carleton player said of his Ole opponents, “They’re no differ-ent than we are. They put their pants on one meter at a time.”

On a 25-degree Celsius day (78 Fahrenheit), David Dye, chairman of the Minnesota Metric Commission, threw out a ceremonial first pass. A Carleton player dropped the pass and Carleton lost the coin toss, a sign of things to come. St. Olaf won the game 43-0, led by 86-kilogram running back Tom Fiebiger’s 70 meters (77 yards). The Oles had 302 meters rushing (330 yards) and 91 meters (99 yards) in the air. Carleton had 106 meters (116 yards), all passing, with zero meters on the ground. As the score mounted, Carleton’s head coach Dale Quist said, “Every meter seemed like a mile to us.” And Carleton’s new president, Bob Edwards, told Mohrig, “De-emphasis of athletics is one thing, but this is ridiculous.”

All panel participants agreed the game was a unique and fun occasion, a collaboration and sharing of resources that brought the two colleges and the town together, strengthen-ing them all as a result. Carleton publicist George Dehne told the Carletonian school paper that an important benefit of the publicity that resulted was “the increased pride that the entire student body feels in having enough ingenuity to attract national attention.” This would induce “a more cohesive and spirited student body” and provide a “more vibrant atmosphere on campus for all to enjoy.”

A Carletonian editorial showed appreciation for the“national recognition” that the metric game brought, but concluded: “Let’s hope that next time, the Carleton football team makes big news because it wins.”

Thanks to Eric Hillemann of the Carleton Archives and Jeff Sauve of the St. Olaf Archives for research assistance. A DVD of the metric football game panel will be made available to the public for viewing at the Northfield Historical Society in the near future. Lite Bowl photos courtesy of Carleton College Archives.

Metric Football Game Attracts National Media

Jerry Mohrig said he first realized this metric game would make big news when the New York Times called him at his office for an interview. He went on to give interviews to the Los Angeles Times, Detroit Free Press and the Chicago Tribune.

The Wall Street Journal, Sports Illustrated, McCalls Magazine and Twin Cities newspapers also wrote about the game and it was featured on network morning shows and WCCO-TV.

Much of this publicity was stirred up by a newcomer to the Carleton public relations department, George Dehne. “He would have made a great used car salesman,” said Mohrig. “This game was a publicist’s dream and he was a very creative guy.” Bob Phelps, who was St. Olaf’s information director, said, “I don’t think you can give George enough credit for this.” Phelps and Dehne coordinated news releases together to spread the word about this game between cross-town rivals.

Saturday morning network cartoon shows had a feature called “In the News” and both Mohrig and Dan Freeman, who had announced the game for KYMN, showed up in a piece about the game in the middle of cartoons, provoking astonished reactions from friends in other states. “It was my 15 seconds of fame,” said Mohrig. Freeman gained another 15 seconds of fame when WCCO-TV televised Freeman’s comment as four St. Olaf linemen sacked the Carleton quarterback: “Oh my, that Carleton quarterback sure has a lot of kilograms on him now!” Subsequently, Armed Forces Television and Radio picked this up and Freeman ended up on television broadcasts throughout the world.

Phelps, who was in the press box, remembered that those covering the game “really got into the carnival type atmosphere of the game…They sort of turned it into a feature rather than hard news coverage.” Minneapolis Tribune writer Joe Soucheray wrote that the half-time show featured a marching band called “Misty Meters and her Hecaliters,” which formed a pocket calculator and played “Fool on the Hill.” (Referring to the one-sided outcome of the game, Soucheray also wrote, rather uncharitably, “This field could have been laid out on Pluto with the same results.”) Phelps said even Soucheray, who “probably would have rather been covering the Gophers and the Buckeyes who were playing that same afternoon,” ended up enjoying himself.

Freeman was grateful for the attention the story brought to Division III football, with “people playing for the love of the game, not for salary or career, not for playing beyond college days.” The Chicago Tribune scribe who was present marveled, “There is no admission price for football games” and he commented on how “the marching student pep band includes instrumentalists who play cello, violin, oboe and guitar.”

Phelps told the panel that the picturesque small town set-ting was “a Norman Rockwell kind of thing,” with “these young, exuberant students running around…And I think that charmed people covering it in the press box that day.”

What Happened to Metric?

When Carleton and St. Olaf played the first metric football game in 1977, the United States was one of only five nations clinging to the old English measurements of yards, feet, inches, miles, pounds, etc. The others: Burma, Liberia, Burundi and Yemen. But the metric system was gaining traction. Road signs and cars speeds were being given in kilometers per hour and most sports were adopting inter-national metric standards. So, Jerry Mohrig, a Carleton chemistry professor accustomed to scientific use of the metric system, felt that a metric football game was certainly in order in 1977. At the panel discussion, Mohrig recalled newspaper articles in the 1970s talking about the inevitability of the metric system if the U.S. was to be able to compete in world trade. Then, after the presidential election of 1980, the talk died down and, said Mohrig, “all of a sudden, it wasn’t American to become metric.” But Mohrig is optimistic that the U.S. may yet go metric. And then, if football sticks with yards and inches, this sport that is “so focused upon distance” will be thought of as “quaint.”

Former St. Olaf football coach Tom Porter told the panel that since football is an American rather than an interna-tional sport, there will be a reluctance to change to metric. And he quoted Dave Nelson, longtime chairman of the NCAA Rules Committee, as saying the main reason that football has not changed to metric is that “None of us on the committee understands the metric system.”