Some people look at cut-down trees and think “Firewood.” Curtis Ingvoldstad of Nerstrand, a wood sculptor/chainsaw artist, looks at the trunks that are left and thinks “Eagle.” Or Bear. Or Root Beer Barrel. Or Civil War Figure. Or whatever else his customers may be longing to see materialize from beloved trees that have been felled.

This 43-year-old Minnesota native has managed to carve out for himself quite an unusual artistic career. You may have seen him May 19 at the launch party for the Northfield ArtsTown website or last July doing demonstrations at the Rice County Fair in Faribault or at Northfield’s Riverwalk Market Fair. These are convenient venues for Ingvoldstad, who moved with his wife, Desiree, and now four-year-old son, Quinn, from St. Paul to a 25-acre farm in Nerstrand in August of 2012. I interviewed Ingvoldstad this past August in his barn/studio shortly after two prize-winning competitions in Eau Claire, Wisconsin, where he nabbed second place in the U.S. Open Chainsaw Sculpture Competition, and Storm Lake, Iowa, where he swept awards in the inaugural “Wood, Wine and Blues” event.

Ingvoldstad described the U.S. Open as a “high level international carving competition.” He had brought a variety of carving tools to his third U.S. Open, including seven different saws. Ingvoldstad sticks to the more expensive pro level carving bars for his chainsaws, which have narrower tips for carving, and goes with professional level saws for power heads. He said, “The big thing for carving is weight to power,” using the “smallest saw with the most power,” since “you are going to be holding that thing for hours and hours.”

The field included artists from the U.S., Japan, Austria, Germany and Australia who had 26 hours in the space of three and a half days to complete their work. Ingvoldstad placed second to Takao Hayashi of Japan, who also placed first last year. Ingvoldstad said he has been “able to develop a really cool friendship” with Hayashi, whose style he characterized as “refined” and “amazing.” The two friends influence and learn from each other’s work, despite their different backgrounds and techniques.

Ingvoldstad explained that “I paint my carvings and he used to just finish his natural with just stain.” Hayashi then was inspired by Ingvoldstad and added painting to his carvings. When they go into competitions, “I know if I want to do well I have to carve everything really clean and really well because I know Hayashi is going to carve his piece that way. And Hayashi knows he’s going to have to finish his piece really well because I am going to finish mine really well.” Despite the adrenalin flowing, it was a friendly rivalry at the U.S. Open, with a “great group of people, a real camaraderie” with everyone sharing tools and helping each other.

Japanese artists are coming to the fore through the efforts of Brian Ruth, a carver from Pennsylvania who started a chainsaw carving school in the 1990s in the small mountain town of Toei in Japan when its lumber market slowed down. In February of 2008, Ingvoldstad met Ruth at a carver gathering in Ridgeway, Pennsylvania. Ruth invited him to Japan where Ingvoldstad took part in what had become Japan’s biggest competition that May. He placed 14th out of 69 carvers. It was part of the learning process for Ingvoldstad, who had carved with a chainsaw for the first time in 1999 and started as a full-time carver in 2007.

Ingvoldstad said that when he first took part in a national competition in 2005 in Hackensack, Minnesota, “I had no idea what I was doing and I mostly watched the other carvers and felt the routine of it.” Currently, Ingvoldstad feels that he just tries to “relax and have fun” and to do “my best carving for the crowd,” showing his skill and what he brings to this art form to the audience and other carvers, while “not really trying to compete with anybody but myself.”

Ingvoldstad grew up in White Bear Lake loving math and science but finding himself drawing or “always making three-dimensional objects.” Despite encouragement from art teachers, “I just shut the door,” thinking “there’s just no money in that.” After graduating from high school in 1988, he went to Iowa State as a pre-engineering student, following the path of his father and brother. But he transferred to the University of Minnesota for his junior year, not quite sure of what he really wanted to do in life. He had an interest assessment that showed “librarian, architect or artist” and, taking into account his math proclivities, took a year of architecture courses, which included his first studio arts class. He ended up with a B.A. in video and performance art.

Ingvoldstad credits performance art teacher Susan Lucey with showing the class how to “bring ourselves out” in creative communication with the audience through the “ritual of art.”

When I asked him what carries over from that to his chainsaw performances, Ingvoldstad said, “I want to make it interesting to the people who are watching so I tend to carve really fast for performances. I want to shoot wood chips around, I want to kick pieces of wood around.” The struggle and the “intensity and energy” inherent in his work is shown, even though it may look effortless. He moves the carving around, so the audience doesn’t think the wood is “some pristine thing.” And he will stop and engage those watching in order to “make the human connection.”

After college, Ingvoldstad went on to do “pretty much anything in the video industry.” When he got laid off in 2007, he finally said to his wife Desiree, “Guess what? I can’t run away from it anymore.” He wanted to pursue art “and see if it will take care of us.” He had been a part-time carving artist from 1999 on, inspired by his father Carsten whose hobby was carving miniature carousel horses. The son soon gravitated toward using power tools and began selling his art at craft shows. Ingvoldstad said he has always liked to be able to work fast and “get things done quickly and efficiently.” He added, “My brain gets really engaged in that.”

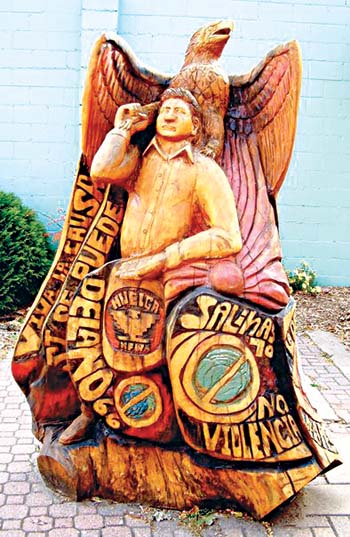

Ingvoldstad had been encouraged to think beyond part-time after completing a major project brought to him in 2005 by Jack Becker of Forecast Public Artworks in St. Paul. Becker asked him to do a bust of Cesar Chavez, the Mexican-American farm worker and civil rights activist in California who co-founded the National Farm Workers Association (later renamed the United Farm Workers union, UFW). Ingvoldstad threw himself into research of his subject, interviewing people who had known Chavez when he spoke in Minnesota. (Ingvoldstad talked to a bodyguard who had accompanied Chavez in 1986 to a speech at Carleton College on reducing agricultural pesticide use.) Ingvoldstad came up with the idea of turning a whole log into a three-dimensional mural with Chavez, an eagle perched above him and the UFW Prayer on the back. The completed work still stands on Cesar Chavez St. in West St. Paul, La Placita, adjoining El Burrito Mercado.

Ingvoldstad had learned that hunger strikes for worker rights had weakened Chavez and may have shortened his life. If Chavez was a martyr who died for his beliefs, Ingvoldstad has a story which he said still gives him chills when he thinks about it. When he was sawing to create an open hand of Chavez, he encountered a nail.

“Nails are not what I want to find with my chainsaw, as it will dull my blade,” Ingvoldstad said. “But it hit me just as I was going to get my nail puller that with all the suffering Chavez went through, it was perfect where it was. So I left the nail in his palm.”

One of his first projects as a full-time chainsaw artist brought Ingvoldstad from his St. Paul home to Northfield in August of 2008. He had been engaged to create a life-size chainsaw rendering of Jesse James during what was called ArtSwirl. Crowds gathered in Bridge Square to watch the outlaw, modeled on current James-Younger gang leader Chip DeMann, emerge from the hunk of wood. At one point Jesse (DeMann) rode into town to critique the artist’s technique. Ingvoldstad remembers how receptive everyone (including the outlaw himself) was to the project and he said he loves how “wide open” and supportive Northfield is to the arts. (Jesse, by the way, was auctioned off for the Northfield Historical Society that November and was bought by Jeff Johnson, who installed it at Northfield’s KYMN radio station.)

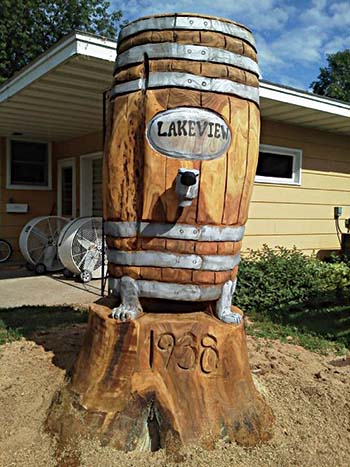

Many projects followed. Here are just a few. When a tree planted around 1900 in the front yard of the former William Hamm house in St. Paul was succumbing in the summer of 2008 to the deadly Dutch elm disease, Ingvoldstad was engaged by Hamm’s Beer history preservationists Karin and Richard DuPaul to saw away to release the Hamm’s Bear they envisioned hiding within the stump. Ingvoldstad said the bear can be seen on the edge of Swede Hollow Park on brewery bus tours. In October of 2008, a Navy submarine veteran in Richfield who loved eagles hired him to carve a six-foot eagle on a Liberty Bell on a giant elm trunk. In 2009, Ingvoldstad helped a seven-foot gnome emerge from a maple tree in West St. Paul. In August of 2011, in the parking lot of Winona’s oldest restaurant, Ingvoldstad in one day converted the tall stump of another dying elm tree into a gigantic root beer barrel to advertise the famous root beer of Lakeview Drive-In. Owner Tim Glowczewksi was quoted as saying, “He worked like an animal!” Ingvoldstad said a perk was “all the root beer I could drink, of course.” By the end, he was exhausted, but it was “a lot of fun to do.” He added, “The hardest things sometimes to carve are the simplest shapes to get them to look right.”

Ingvoldstad spent a week in Ames, Iowa, in April of 2012 carving a totem of six Civil War figures out of the trunk of a sugar maple at the home of Civil War enthusiast Jerry Litzel: Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses S. Grant, George A. Custer, Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, and Jefferson Davis. Ingvoldstad said this was a “good challenge for me,” giving him a chance to stretch his abilities to do faces. After this, he traveled to Roscoe, Montana, to carve a Norwegian troll, having a “fun time with mountain men and ranchers.”

On June 2-3, 2012, came a culmination of a challenging commission brought to him again by Jack Becker: to create public art out of a tree trunk for the Flint Hills International Children’s Festival of the Ordway Center for the Performing Arts in St. Paul. Ingvoldstad’s work was put into a Story Time Garden in Hamm’s Plaza and, appropriately, he has quite a story to tell about how “everything just kind of came together.”

What a tree trunk it was! Ingvoldstad said the forestry department had a 100-year-old gigantic cottonwood with a huge root ball on it which had gotten hung up under a city dock and had been extracted from the Mississippi River by crane. The idea for the art was to turn the trunk upside down, so the roots became flowering branches. Ingvoldstad was apprehensive, at first, about how it would balance but in a “crazy feat of engineering,” the forestry department chained and roped it to other trees and created a base around it so he could work on it.

The sculpture has a collage of painted animals on it, with a “storyteller” face dominating the carving. Ingvoldstad modeled the face on a picture of a forestry worker named Joe “Gonzo” Misiewicz, who had died at 49 of cancer in 2009. His colleagues wanted to honor this man who loved trees and had a big mustache, big eyebrows, big eyes and big, white front teeth. Ingvoldstad was touched when he realized that Gonzo had helped him during the Cesar Chavez project in 2008 and now was being memorialized in this fashion. After the event, the 20-foot tall, 5,850-pound tree was mounted on a concrete slab in front of the forestry offices at 1120 N. Hamline Ave.

This past winter, Ingvoldstad carved the eagles on top of the trophies given out for the Red Bull Crashed Ice World Championship in St. Paul. Ingvoldstad said he designed the eagles so they look like they have a “skater movement” going down a course. He also carved the Minnesota Wild hockey logo in a three-hour show for a conference at Xcel Energy Center. After his award-winning summer, he performed in mid-September for the 7th time at Minnesota’s largest winery for the Carlos Creek Winery Grape Stomp event near Alexandria.

Ingvoldstad can demonstrate his art at any special occasion –festivals, parties, corporate events and the like – and told me he is “starting to do more modern slab furniture design too.” He can custom-design almost anything, including benches, mantels, beds and relief carved wood panels.

The artist also enjoys visiting schools. When he visited Elk River’s Twin Lakes Elementary School in the fall of 2011, he carved a bald eagle for them and then delighted the students by creating Ollie the Otter, the mascot of their school. The teacher said, “Now all of the students want to hug or pet our otter… Ollie is a big deal at our school.” Several youngsters announced intentions of becoming chainsaw artists. Ingvoldstad is pleased to be able to illustrate the creative process that is involved in art, demonstrating how art does not just “show up.”

Ingvoldstad reflected on what his art means to people. He carves many eagles and “just watching the eagle fly, I know why that’s inspiring.” People want to relive that kind of inspirational feeling “because for them, it betters their life.” Ingvoldstad asks many questions in his commission work so that no matter how simple the subject matter, the customer has “the thing that they are looking for in the end.” Perhaps they want to save a tree or just enjoy watching the creative process. Ingvoldstad said, “What I do, it’s a service like anything else” and “no less valuable than good plumbing or good carpentry.”

Today’s artists can produce finer detail than “cabin kitsch” of the past, due to training in art and new tools which, said Ingvoldstad, lead to “more dynamic compositions.” He added that he can use a chainsaw more effectively than a knife, since a saw speeds up the process so much. And once he has assimilated the research and planned things out in his head, it goes faster and better “because my brain is so clear on what it’s supposed to look like that it’s just a matter of waiting for the saws to cut.”

Ingvoldstad was pleased to show me around his property, which at one time had been the Hukee Dairy. He said that when he first walked into the 30-foot tall, spacious barn, “my heart just kind of went BOOOM, this is your studio.” His wife Desiree felt at home in this area because she had grown up in Northfield where her father Fred Fintel owned the Ideal Café at 317 Division St. Ingvoldstad also had a connection because a railroad bed runs through their land from a railway which once carried his grandfather Carsten Ingvoldstad (a 1926 St. Olaf graduate from Iowa) to and from college.

A part of their property is in the Nerstrand Big Woods, legendary for having over 200 varieties of wildflowers (including the endangered dwarf trout lily). And, appropriately, the Big Woods has been noted for sugar maple, basswood, oak, hickory, aspen, elm, ash and ironwood trees.

Who knows what objects lurk within such trees, just waiting for a talented chainsaw artist to release them?

Curtis Ingvoldstad’s website is woodsculpture.net.