No, I am not writing about the Northfield Cannon Valley Lions Club. Nor am I writing about the St. Olaf Lion, logo of the college and former name of athletic teams before “Oles” took over.

In August of 2007, I wrote a Historic Happenings column about two events that happened in August of 1915 and 1929 involving real lions in Northfield, one tragic and one not. I am revisiting that theme, in more detail.

On Aug. 19, 1915, the Northfield Independent announced “Carnival Shows Draw Big Crowds. Many Clever and Interesting Performances to be Seen with Patterson Carnival Company, Now Exhibiting Here.” The scene was “the little triangle at the north end of West Water Street,” which was called “the gayest and most populous spot in Northfield.” It was “brilliantly lighted by electricity” with show people lending the tent city “an air of oriental enchantment.” The main show featured “a number of animal acts that are extremely clever.”

The audience on the night of the 19th watched as bears lumbered through their paces. Then the lion tamer, known as Major Dumond, ushered the lions to their places on pedestals within the performing cage of the arena as they came in by way of a passageway from the adjoining wagons.

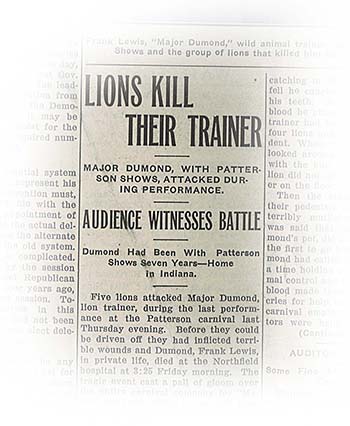

What happened next was captured in the astonishing Northfield Independent headline on Aug. 26: “Tragic Death Palls Carnival Festivity…Lion Trainer with Patterson Shows Dies in Hospital, Following Battle with Lions in Cage. Tragedy Enacted Before Audience of 300 People.”

Four of the lions had taken their places and the big male lion, Romeo, was entering when, according to some accounts, the sliding door to the cage fell on his tail. Enraged, he attacked the trainer. Another story held by the carnival people was that Romeo had fallen off his pedestal, which made him excited and caused him to lash out and grab Dumond’s thigh with his giant teeth. Startled and in pain, Major Dumond struck a blow with his whip but the lion did not loosen his grip and threw the man to the floor. Two other lions then leaped from pedestals and attacked, one almost tearing off Dumond’s ear, the other seizing him by the throat and shoulder, “evidently trying to tear him to pieces,” according to the Northfield Independent.

The Northfield News of Aug. 27 wrote that Dumond had “called his lions by name, for a time holding them off by sheer animal control and nerve, but the sight of blood made them beyond control. His cries for help were agonizing, but the carnival employees and spectators were helpless. At the express command of Dumond, who preferred to rule by kindness instead of force, no firearms were kept in the tent.” Dumond had raised and trained all five lions.

The horrified spectators ran for exits or crowded around the stage, unable to stop the carnage. Show attendants poked at the lions with long bars through the cage to no avail. Finally, after several agonizing minutes, Patterson (the owner of the show) shot and killed Romeo with a revolver while other show people emptied chambers of .22 caliber rifles taken from a nearby shooting gallery at the other lions. The wounded lions finally released their victim and retreated to the corner of the cage. Dumond’s wife, Grace, part of another show act, became hysterical and fainted when told what had happened. They had been married just weeks earlier in Minneapolis.

Although the trainer was rushed to the Northfield hospital, Dumond died at 3:25 in the morning. The attending doctor later said that reports that Dumond had been disemboweled by the lions (as in the Milwaukee Journal of Aug. 20) were not true. Dumond died from loss of blood.

Later on that Friday, Aug. 20, townspeople and carnival members formed a funeral procession and, led by a band playing hymns, marched from the show grounds to the undertaker for a service. Dumond’s remains were sent to his parents for burial in Nabbs, Indiana. Dumond’s real name was Frank Lewis and the newlywed was 32 years old.

In a letter dated Aug. 23, printed in the Northfield News of Aug. 27, the Lewis family gave their thanks to the citizens of Northfield “for your kindness and sympathies shown in our recent trouble” and for the “beautiful floral offerings.”

Dumond may have had a premonition of his demise. The show people said that shortly before the performance, Dumond and his wife had witnessed a little dog being run over and killed by a car and he told her, “You saw what happened to that dog. That’s what will happen to me some day.” Dumond had also commented that the lions had seemed to dislike his change from a khaki to a blue uniform.

Major Dumond was an experienced lion trainer of great reputation. I found a reference to Dumond’s performance in the Waterloo Semi Weekly Courier of July 30, 1909. He was listed as a “feature attraction” with “trained wild animals” and his act was presented as “the fight for life of Major Dumond in the iron bound den of the untamable lion, Mayo.” Unfortunately, six years later in 1915, it was to be a “fight for life” which he would lose to the lions in Northfield.

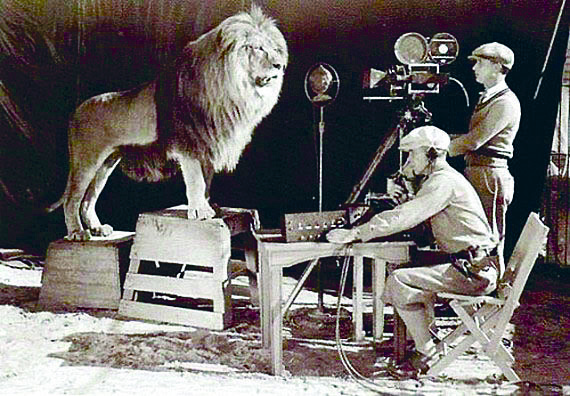

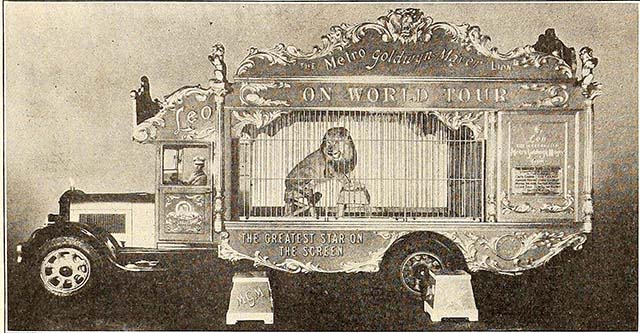

A much happier lion tale happened on another August day, on Aug. 10 in 1929. Leo, the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer lion, paid Northfield a visit on his world tour. The lion, who was famous for roaring from inside a wreath of film strips at the beginning of MGM movies, made a stop at the Grand Theater. The Northfield News of Aug. 9 heralded his appearance in an article detailing the trappings of this feline celebrity.

The motion picture company spent $100,000 on the fleet of motor cars and truck of the caravan transporting Leo. The article said that Leo’s huge, motorized speed truck “has been described as the most magnificent and palatial vehicle ever designed for any animal.” It was 24 feet overall, with Leo’s private cage occupying 13 feet. Within the golden bars of the cage, “Leo’s comfort and health is assured by white tile floor and walls, electric lights, sanitary watering and feeding troughs, unbreakable glass sides three feet high, and canvas drops that can be lowered in inclement weather.”

Two other cars in the entourage matched “the magnificence of the one in which Leo rides.” One had the business office of his manager who was conducting the tour. This office had typewriter, desks, chairs, files and all office accessories. The third one transported the huge 57-note calliope, “the largest musical instrument of its kind ever constructed.” So we know that music was part of whatever performance Leo put on at the Grand 85 years ago.

At least five lions have been used as the lion logo since it was first employed for Goldwyn Pictures Corporation, formed in 1916. It became a trademark when Goldwyn merged with Metro Pictures and Louis B. Mayer to become MGM in 1924. Publicist Howard Dietz is often credited with designing the original lion mascot as a tribute to the athletic team, the Lions, of his alma mater, Columbia University. Credit has also been given to Paramount Studios art director Lionel S. Reiss. At any rate, Dietz was certainly responsible for “exploitation ballyhoos” (an advertising term meaning stirring up interest by sensational methods) for the newly created MGM which resulted in Leo’s arrival in Northfield in all his glory.

From 1924 to 1954 MGM dominated the motion picture industry, even through the depths of the Depression as people sought escape in films. And Dietz knew how to promote the brand. From March of 1925 to March of 1926, MGM and the U.S. Tire Co. ran the world’s first trackless transcontinental train from New York to Los Angeles, publicizing MGM, tires and development of a national highway system. The vehicle looked like a locomotive train, with engine, cab and dining/sleeping car, but operated like a truck. It had two motors which enabled a top speed of 35 mph. The train toured Canada and then was shipped to Europe to continue on a world tour, starting in Great Britain in June of 1926, finally reaching 33 countries in four years.

In September of 1927, the lionizing (if you will) of Lindbergh’s cross-Atlantic flight led MGM to try to fly their lion Leo from San Diego to New York in a cage right behind the cockpit of pilot Martin Jensen. The overloaded plane (which included a 350-pound lion, remember) got only as far as Arizona when it crashed in the area called Hell’s Gate Wilderness near Payson. Both lion and aviator survived, but Jensen had to walk for days for help, leaving Leo with some water and a couple sandwiches. The successful return to rescue the lion provoked extraordinary, undreamed-of publicity for MGM. An account by Arizona writer Gail Hearne says that a rescue party made up of local cowboys plus the animal trainer and Jensen hiked into the remote canyon with a sled and two teams of mules to pull the caged lion out. The lion had been waiting six days in that cage for sustenance and rescue. By the time they got him back to Payson, he had roared so much, he couldn’t roar anymore. The steep canyon of the crash is now named Leo Canyon. (The wrecked plane, by the way, was finally salvaged by Scott Gifford of Prescott, Arizona, in 1991.)

The Leo that visited Northfield in 1929 was most likely the second MGM lion, called Jackie. (The first Leo, named Slats, was used for MGM between 1924 and 1928.) Jackie supposedly was captured as a cub in the Nubian desert of the Sudan. He was the first lion whose roar was heard by way of a gramophone recording during MGM’s first sound production, White Shadows in the South Seas (1928). Jackie’s roar appeared in all the black and white MGM films from 1928-1956. You can see Jackie during the opening credits of The Wizard of Oz (1939) and he performed in movies, including those starring Tarzan. It is said that he earned $1,000 a week.

The trade paper Exhibitors Herald and Moving Picture World of April-June 1929, publicizes the world tour of the MGM lion.

The tour which brought Leo the Lion (aka Jackie) to Northfield had its inception in 1928 with the announcement on June 9 in the trade paper The Exhibitors Herald and Moving Picture World that a tour of the world was planned for Leo the Lion. By July of 1928, the Trackless Train tour had reached South America and Australia. Now Leo the Lion would start his tour in Washington, D.C., in July that same year with a million dollar insurance contract, including $100,000 if Leo escaped his cage and $300,000 if he injured anyone. Luncheons and receptions were held at the National Press Club with Army and Navy representatives and it was noted that “Thursday Leo was host to inmates of the National Zoological Park with meat as gifts.” An Eastern tour followed with his trainer, Capt. Frank Phillips, and a four-man staff. On Dec. 29, the trade paper cheered that 1928 would be noted for “shadows of the screen drama” finding their voice and for MGM’s Leo the Lion emulating the globe-trotting trackless train. At the end of the tour, one report said that Leo had been viewed by 50 million Americans.

This movie poster from 1928 announces the personal appearance of Leo the Lion at towns throughout his highly publicized world tour which brought him to Northfield on Aug. 10, 1929.

On the Internet, stories of the original MGM lion Slats and second lion Jackie seem to have intermingled. And, contrary to some Internet rumors, none of the MGM lions ever killed their trainers, as was the fate of Major Dumond in 1915. Volney Phifer, who was the first trainer of Slats and Jackie, outlived them by decades, dying in 1974. Volney buried one of the lions on his 13-acre farm in Gillette, New Jersey, where he boarded animals used on Broadway.

In June of 2011, according to mycentraljersey.com, a film crew from Ireland came to Gillette to do an investigatory documentary to try to prove that Leo was actually born in the Dublin Zoo. They hoped to try to determine origin by taking samples of both the remains of Leo in N.J. and of the hide which was made into a rug and somehow ended up at the McPherson Museum in Kansas. I could not find the result. But the Phifer estate was auctioned off in 2012 and the property was sold to a Leo the Lion fan so it is hoped Leo can rest in peace after his adventurous life. On his world tour, after the plane crash, he survived two train wrecks, a flood in Mississippi, an earthquake in California and a fire. Leo was truly a cat with nine lives, and it is a fascinating “historic happening” that he visited Northfield during one of those lives.

Thanks to Jamie Stanley, Northfield Public Library reference librarian, and Carol Donelan, chair and associate professor of Cinema and Media Studies at Carleton College, for assistance with this story.