No doubt fans of football at St. Olaf looked enviously across the Cannon River during the first two decades of the 20th century when autumn brought football fever to town. As described in last month’s “Historic Happenings” column, the right to play what was considered to be dangerous intercollegiate football was regularly turned down at St. Olaf, despite numerous student petitions. Interclass games had to suffice, where lack of training and coaching could sometimes create as many injuries as intercollegiate competition. Meanwhile, Carleton (which had its first sanctioned football team in 1891) had outscored opponents 1,520 points to 79 between 1910-1917, with 66 wins, 17 losses and two ties over the years 1905-1917 and had upset the University of Chicago 7-0 at Chicago in 1916. And Northfield High School had been playing football against other schools since 1892 (including against Carleton). It was no wonder that St. Olaf students agitated to be able to join this football fraternity.

Intercollegiate football was finally recommended by the St. Olaf faculty in 1917 and approved for colleges of the Norwegian Lutheran Church in 1918. But the first season of intercollegiate football for St. Olaf in the fall of 1918 brought an unlikely pairing. There were Student Army Training Corps units at colleges due to World War I, and a Northfield Independent story on Oct. 17, 1918, said, “All military and athletic operations at Carleton and St. Olaf colleges have been organized on an entirely military basis and will be carried out hereafter as if by one unit under the name Carleton-St. Olaf.”

Between 20 and 25 men from St. Olaf were taken by bus to Laird Field each afternoon to practice with teammates from cross-town rival Carleton, under Carleton’s coach Howard Buck.

The first game was played Oct. 19, with a resounding 40-0 win over Pillsbury Academy of Owatonna. The Manitou Messenger account on Oct. 22 noted that, from the beginning, “the S.A.T.C. unit surpassed their opponents in every aspect, and had the game well in hand…The game as a whole was full of vim and pep from beginning to end. Spirited action and novel plays were common features of the game.” The writer praised the Pillsbury team for playing “a steady and clean game,” but said they were outclassed by the “husky” S.A.T.C. team. Godfrey of Carleton “won for himself admiration by a beautiful 65-yard run” and Thune of St. Olaf had “repeated brilliant gains” and “again and again brought the crowd to their feet with a roar.” History was made that day, said the writer, as “the Oles were let loose, “with a “vision materialized.” The two colleges had met for “common purpose upon the gridiron” and “a new and closer bond of friendship has been formed.” The writer encouraged this bond to be strengthened and kept “as we mix from time to time in our athletic contests.”

Alas, in a summary of the 1918 football season in Carleton’s Algol yearbook, the writer claimed that there was “deadly antagonism” from the start in the combined team: “The interest was in the colleges, rather than the unit, and the student bodies gave credit only to their representatives on the team. With such spirit, it was impossible to produce a good team.”

The next game for the combined squad was a 59-6 loss to the University of Minnesota at Lexington Park field in St. Paul on Nov. 2 on a “slippery” field. The Northfield News account of the game on Nov. 8 said, “The light Unit line put up a hard fight and got many Minnesota runners for losses.” The Unit missed the defensive play of the team captain, who became ill the night before the game. It is possible that the captain had contracted the Spanish influenza which became an epidemic that fall and led to the disbanding of the S.A.T.C. team after only a couple contests. But Carleton and St. Olaf players organized themselves to play three other games against each other, with Carleton taking two of the three.

The first St. Olaf team to play a full season in 1919 had a 2-3 record under its first football coach, Endre Anderson, including a 15-7 loss to Carleton. By the time Anderson departed in 1928, his record was 34-25-3. In 1922, his team was undefeated, tied St. Thomas for the Minnesota Conference championship and had secured its first official win over Carleton, 19-0. As at Notre Dame, St. Olaf had its own “Four Horsemen” as leaders for its conference championship run of 1923: Carl “Cully” Swanson, Harry “Whitey” Fevold, Frank Cleve and Ingvald Glesne. Fevold was the only St. Olaf athlete to win 16 letters and had the longest drop-kick field goal in the state at 45 yards. Swanson was featured in Robert Ripley’s “Believe It or Not,” which was syndicated to newspapers all over the country, for his 1924 record of having 121 completions in 226 attempts for 1,644 yards, an average of 205 ½ yards passing for eight consecutive games.

Ade Christenson became football coach at St. Olaf in 1929 and held that position from 1929-42,1946-48 and 1951-57, with an overall record of 101-75-11. One highlight of his long career was the 1930 football team which, along with upsetting South Dakota State, kept pace with colleges such as Alabama and Notre Dame by being one of only 11 undefeated, untied college football teams that year. It was the top-scoring team with 302 points in eight games. The $30,000, 15-acre Manitou Field was inaugurated this year. Also in 1930, Northfield native Harry Newby’s achievement of scoring on his first play in four consecutive games was featured on Nov. 29 in Ripley’s “Believe It or Not.” Though he weighed only 147 pounds, Newby had touchdown runs of 58, 72, 45 and 35 yards. He was used sparingly, playing a total of only 16 minutes in those four games. The Northfield News said, “The Northfield boy is a racehorse, not a work horse. Did Dan Patch [a famous racehorse] help with the fall plowing?”

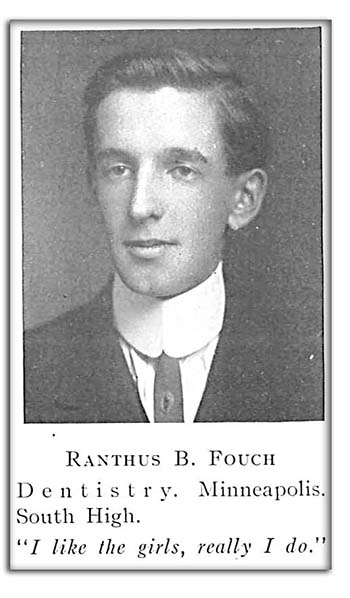

The year 1931 brought the inauguration of the first football “Goatrophy,” awarded that first year to St. Olaf for its 25-6 victory over Carleton. As described in the November Entertainment Guide, the trophy given each year to the Carleton-St. Olaf football winner was designed by Dr. R.B. Fouch, who also created the “Slab of Bacon” trophy fought for by the universities of Minnesota and Wisconsin from 1930-43. Further investigation has revealed that Dr. Ranthus B. Fouch was a graduate of the college of dentistry at the University of Minnesota in 1914 (see photo). In a phone call, Fouch’s son, Ranthus B. Fouch, Jr., of Lewisburg, W.Va., told me that his father, who was killed in a 1945 auto accident, had a workshop at his dental office in Minneapolis and was an artist who was quite “handy with small tools.” Ranthus, Jr., was aware his father had carved the “Slab of Bacon” trophy, but had not heard about the “Goatrophy.” He was interested to learn that his father’s “Goatrophy” is still exchanged in Northfield. This year, on Oct. 3, Carleton won the bragging rights with a 17-13 win over St. Olaf, retaining the goat and keeping the eagle on top of the Civil War statue in Bridge Square facing east. St. Olaf holds the overall 46-43-1 advantage between the two teams.

George Gibson was head coach at Carleton from 1934-38. In his first season, the team finished 6-1 and outscored opponents 85-14, with shutouts in five of the seven games. His 1936 team won the Midwest Conference title, with its only loss coming to the University of Iowa, 14-0 (the last game played against a Big Ten team). Carleton had previously played against the University of Wisconsin in 1922 and 1930, Northwestern in 1925 and 1926 and against Army at West Point in 1928 and 1932 (no wins).

Carleton had no football teams during the war years of 1943-45. St. Olaf had 20 recruits for the 1943 season, but only half had prior experience. Only three games were played, with two losses to River Falls Normal and a Homecoming victory over Luther. In the 1944 and 1945 seasons, Navy cadets on campus were allowed to compete for St. Olaf.

Post-war highlights through 1950 include St. Olaf’s first west coast trip in 1947 to compete against Pacific Lutheran University in Washington (a 14-0 loss) and Carleton’s 1948 team which, bolstered by returning veterans, allowed only 52 points in eight games. In a 1950 game at Grinnell College, Carleton won 21-19 by scoring two touchdowns in the last 32 seconds.

In 1950, Carleton students voted to adopt the name “Knights” as a team name for varsity sports. At St. Olaf, the team once known as the Vikings was renamed the Lions after the lion on the St. Olaf seal in 1941. But for many people, it will always be “Oles” and “Carls” doing battle on the field. And few will remember the fall of 1918 when the Oles and the Carls were teammates.

Thanks to Eric Hillemann of the Carleton Archives, Jeff Sauve of the St. Olaf Archives, coaches Tom Porter, Bob Sullivan and Jim Dimick, Erin George of the University of Minnesota Archives, R.B. Fouch, Jr., and historian and curator Kent Stephens from the College Football Hall of Fame.

St. Olaf Face Mask in the College Football Hall of Fame

When Tom Porter (St. Olaf football coach from 1958-1990) was researching his 2005 book of St. Olaf College football history, “The Greatest Game,” he visited with Al Droen, a member of the 1930 undefeated football team and a 1931 Honor Athlete. Droen told Porter that the College Football Hall of Fame had accepted a face mask he had offered to them for their collection of memorabilia.

Kent Stephens, historian and curator of the College Football Hall of Fame in South Bend, Indiana, confirmed to me that in October of 1996, Al Droen of Inver Grove Heights, Minnesota, came in to the Hall of Fame with a “personal artifact” he wished to share.

“Mr. Droen informed me that he played college football in the late 1920s and early 1930s at St. Olaf College. And that due to injury he sustained, he created a metal face mask to protect himself from further injury. The face mask looked to be reminiscent of a Phantom of the Opera mask. Inside the mask were the remnants of a leather pad that was riveted to the inside of the mask. With the passage of time, I have forgotten how Droen wore the mask. But as no means of affixing the mask to a strap or the helmet appears evident, I can only assume that the mask was form-fitting. His mask became one of our collection’s unique oddities and it is exhibited frequently.”

Stephens explained that before face masks became commercially produced in the 1940s, “several players created home-made face masks. In our collection we have two or three other home-made masks. The most famous belonged to Jay Berwanger, the first Heisman trophy winner from the University of Chicago. His elementary bird cage face mask earned him the nickname of the ‘Man in the Iron Mask.’ Another in our collection was a quite detailed bird cage face mask designed by Jack Kaava of Hawaii in the mid 1930s. In an era where grabbing the face mask was perfectly legal, Kaava remedied this tactic by having barbs placed at several points on the face mask. The Droen mask is unique in that it is not a precursor to today’s face masks but an applied form of protection.”

Porter said that Droen was “anxious to get back into play” after a facial injury and “had the mask formed by someone in the Carpenter Shop at the College.” On at least one occasion, according to what Droen told Porter, “a game official denied him permission to play while wearing the mask.”

In a Northfield News story of Nov. 20, 1931, Droen was described as “a great blocker and runner, and a fine low hurdler. He probably gets more fun out of hitting and being hit hard than any gridster in Northfield.” No doubt having the face mask helped.