“Until Dec. 7, 1941, I thought I was a normal boy, a normal American. All of a sudden I was dirty. All of a sudden I was sinister. All of a sudden I couldn’t be trusted.” These were the words of Yoshiteru Murakami, native Californian of Japanese ancestry, about what happened after Pearl Harbor. “We were assigned numbers, herded into a troop train and shipped to a place a few hours away. That evening we arrived at a relocation camp in the Mojave Desert. For two years, tarpaper barracks with loosely constructed floors were the only home and straw-filled bags covered with blankets the only beds for about 10,000 Japanese-Americans crowded into one square mile, surrounded by barbed wire fences and sentry towers.”

“Until Dec. 7, 1941, I thought I was a normal boy, a normal American. All of a sudden I was dirty. All of a sudden I was sinister. All of a sudden I couldn’t be trusted.” These were the words of Yoshiteru Murakami, native Californian of Japanese ancestry, about what happened after Pearl Harbor. “We were assigned numbers, herded into a troop train and shipped to a place a few hours away. That evening we arrived at a relocation camp in the Mojave Desert. For two years, tarpaper barracks with loosely constructed floors were the only home and straw-filled bags covered with blankets the only beds for about 10,000 Japanese-Americans crowded into one square mile, surrounded by barbed wire fences and sentry towers.”

“Yosh,” as he was known to one and all during his years at St. Olaf College and as a Northfield school music teacher, did not dwell on this experience but did not downplay it, either. Kathy Budd Peterson, Northfield High School Class of 1969, said, “I felt kind of ashamed this good person would have to go through that.” In a speech he once gave, Yosh said that in spite of the interment, “This is the best country I know. This is where I want to live, this is where I want to die, this is where I want to raise my children. And, if this country is attacked, I will serve to defend it.”

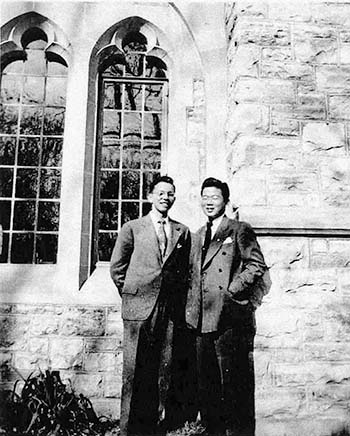

Jeff Sauve, St. Olaf’s Associate College Archivist, has researched how St. Olaf College took in Japanese-American students in the wake of Pearl Harbor. At a time when many universities, including the University of Minnesota, were denying admissions to Japanese-American students, St. Olaf’s acting president J. Jorgen Thompson called a meeting of the administrative officers in August of 1942 at which it was “unanimously decided that American citizens of Japanese origin will be given the same opportunities as all other students at St. Olaf College.” The first three Nisei (second-generation Japanese American) students arrived in January and early February of 1943 and Sauve found that from the spring of 1943 until the fall of 1944, “a total of 10 Japanese-American students, representing 7 of the 10 relocation camps, enrolled in St. Olaf College.” Helen Kinoshita and Yosh Murakami were members of the St. Olaf Choir, the “first ever students of color in the Choir,” according to Sauve. Murakami also served as director of the Viking Male Chorus.

Yosh interrupted his studies to serve in the U.S. military as a Japanese interpreter with the army of occupation from 1946-48, and returned to St. Olaf to finish his degree in public school music. In Japan, he had met Mikiko (Miki) Anzai and was able to bring her to be his bride through a special bill introduced in Congress by Senator Edward Thye (a Northfielder) and signed by President Truman.

After his graduation from St. Olaf in 1951, the couple was married that July and Yosh became a new hire in the Northfield public school system. Paul Stoughton, director of music from 1935-73, first became acquainted with Yosh when Yosh was a student teacher under him at Northfield High School in the spring of 1951. “I would like to have people think that I deserve the credit for recognizing his worth and hiring him,” Stoughton wrote in 1975. “Actually, appropriately enough, it was the students who were responsible. High school students have more than teachers the instinct for instantly separating the talented from the incompetent and the real from the phony, and by the time Yosh had finished his term of practice teaching, their feelings toward him were so obvious that there would have been little choice in my offering him the place on the music staff that happened to open up. The result has become Northfield history.”

Stoughton wrote of Yosh’s musical standards: “There was no humbleness about his demands for high standards in musical performance. Most of his students will remember the sign on the wall of his rehearsal room: ‘If you think that your results are perfect, maybe your standards are imperfect.’ He insisted on every student doing his best, and under his stimulation students more often than not achieved a little better than their best.”

Marilyn Sellars (NHS Class of 1956), who has achieved success as a professional singer, told me that Yosh Murakami was “phenomenal. We just adored him.” He was “generous, kind and inspirational” to his students as he upheld his high standards. “He knew instinctively how to encourage and inspire us. He had a way of getting our attention without having to say a word (like moving ONE little finger to raise or lower our volume) and to inspire us to (always!) try harder.” Yosh encouraged her to try classical music and to join in all the musical groups that he started, as well as Choir and Madrigals. He also put her in touch with Gertrude Boe Overby, a noted St. Olaf voice instructor, for lessons. Sellars said, “They helped me develop my voice and they both are responsible for my never having had problems with my voice in all these years, because they taught me how to use my voice correctly. I am so grateful to them both. I still ‘practice what they preached’ to this day.”

Maggie Lee wrote in the Northfield News of May 28, 1993, that “Yosh filled a valuable niche in Northfield at a time when blacks were experiencing a particular amount of bigotry. He was well accepted and he could draw people together. To frustrated blacks he would tell about the persecution he had experienced on the West coast, yet emphasize his love of his country. He was an excellent teacher and was much loved by his students.” His wife Miki picked up English quickly and was “warmly accepted.” (Their four children were born in Northfield: Paul, Stephen, Jane and Jonathan.) Lee wrote that “there was always much humor” as “Yosh made jokes about being Norwegian and about the Norwegian customs, objects and food that are common in Northfield.”

Ken and Carolyn Jennings, long-time members of the St. Olaf music faculty, told me, “We remember Yosh as a highly respected choral conductor/teacher who related very well to young people. He also identified to an amazing degree with Northfield’s largely Scandinavian and north European population. Once, after returning from a family vacation to Europe, the whole family sported Norwegian sweaters. And when Yosh was asked about the various countries they had visited, he replied that Italy didn’t feel so comfortable, but they really liked Norway. ‘They’re more like us,’ he added.”

Stoughton also noted Yosh’s “significant contribution to the cause of racial tolerance,” saying, “At the time he was hired, it was still close enough to the end of the war that there was considerable resistance to anything Japanese. Students very quickly learned to value him as a human being and not as a member of a particular race.” Yet, said Stoughton, “In an era when ethnic jokes are in many circles regarded as an attack on personality, he not only allowed but created many jokes about his ancestry. I remember one occasion when he disrupted the composure of a blood bank staff. A nurse asked him the usual question abut whether he had ever suffered from jaundice. When he, in feigned innocence, asked what the symptoms were, she explained that the skin often turns yellow. ‘I’ve had it all my life,’ chuckled Yosh.”

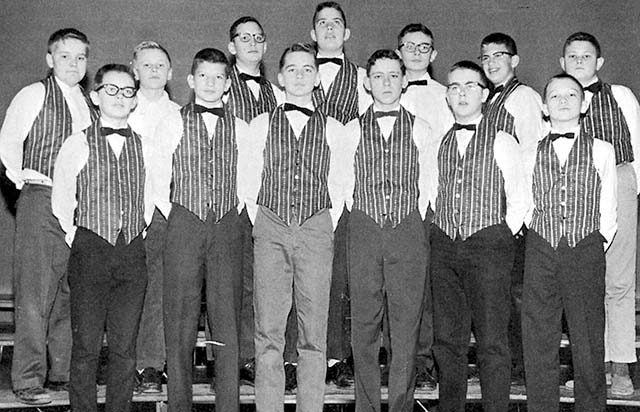

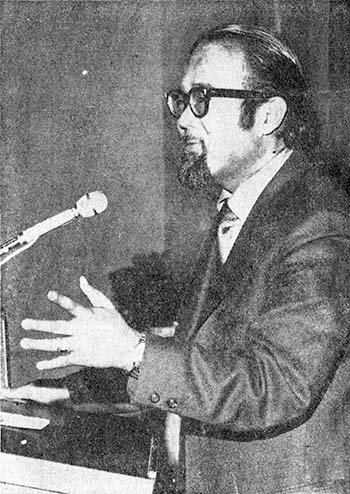

Murakami had a very active role in local and state music, especially after taking over the senior high choir from Stoughton in 1954. A Northfield News story on Sept. 4, 1958, shows him at work on “voluminous correspondence” after helping select the music for the 1,200 voice All-State Chorus in Minneapolis in his role as vice-president of the Minnesota Music Educators Association. The program, celebrating Minnesota’s centennial year, included the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra. The Northfield Independent then ran a front-page headline on Sept. 15, 1958, about the results of a Minnesota Centennial State Fair contest win for the Northfield High School Choir: “Choir Called Best in State. Yosh’s Choristers Win Top Rating at State Fair.” A trophy was later presented to the school during N.H.S. homecoming weekend. The choir was one of ten choirs that had sung on various days of the fair, chosen by a poll of high school choir directors in Minnesota.

Yosh also had time for extracurricular fun. Gary Anderson, NHS Class of 1967, remembers a band which was put together for Crazy Days, with himself on clarinet, his father Phil Anderson on trumpet, band director Jim Anderson (no relation) on tuba and Yosh on alto saxophone. “We strolled up and down Division Street playing polkas and old-time music” said Anderson, and they called themselves “Five Slender Swedes.”

An “Epiphany letter” of the Murakami family from 1967, found in the St. Olaf Archives, notes that Mikiko’s holiday baking of “Krumkake, lefse, and other Scandinavian goodies are turning out very well.” They wrote that Yosh “found this year a challenging year since moving into the brand new $2,750,000 high school.” He had to commute back and forth between junior and senior high schools for 16 singing groups and for two Christmas concerts. “Claims he will resign from teaching if they should ask him to prepare the elementary Christmas concert too!”

In the spring of 1968, the 240 students of the various choirs led by Yosh plotted a surprise for their director. Yosh had not seen his parents, Mr. and Mrs. Motoyoshi Murakami of Long Beach, California, for six years. Oliver Towne, columnist for the St. Paul Pioneer Press and Dispatch, wrote about what happened.

Along about April, the choir students decided that it would be nice if Yosh’s parents could be in Northfield for the annual high school pop concert. So they all chipped in from $3 to $5, then told Miki what was planned and asked if she’d play the role of intermediary – without telling Yosh. They wanted it to be a big surprise.

And it was. The night of the big concert, as Yosh got up to lead the choirs, a student stood to tell the guests that since the 17th of May was Norwegian Independence Day, and since they had a ‘Norwegian’ director, the students were about to present two special guests. Yosh, thinking he would be greeting Dr. Olaf Christiansen, retiring director of the St. Olaf College Choir, turned to bow — and found himself facing his mother and father.

Nobody is quite clear on what happened after that. Because you can’t see clearly with tears in your eyes. They ran down Yosh’s cheeks like rain and the choir members’ cheeks like a waterfall and also the faces of the 500 persons in the audience. Not to mention the senior Murakamis who didn’t forget the Japanese custom of returning a gift for a gift. Yosh’s father wound up the event by presenting the choirs with $50 for their annual picnic.

Now, what were you saying about today’s younger generation?

It was to be Yosh’s last concert in Northfield in his 17-year career. He accepted an offer to serve on the music faculty of Concordia College at Moorhead and as director of music at Trinity Lutheran Church there. He taught at Concordia until 1971, then worked for the Fargo public schools.

Marilyn Sellars told me that the last time she saw Yosh was when she was appearing in a nightclub in Fargo after her first album, “One Day at a Time,” went to number one on the top country LP list in October, 1974. She said, “I was so honored when he asked me to come and speak to his high school choir about my recording experiences in Nashville and to share what it was really like to be in the (country) music business.” Yosh Murakami died suddenly several weeks later. In Sellars’ words, “He left us too soon.”

Maggie Lee wrote that Yosh died Jan. 13, 1975, “after a short and very severe illness. The autopsy showed that the death cause was Addison’s disease, the primary clue to which is the yellowing of the skin. But of course his skin was that color to start with and, tragically, the nature of the disease was not detected. He was only 48.”

Northfielders were stunned and many drove up to join more than 1,000 others at the memorial service in Moorhead. From his retirement home in Arizona, Stoughton wrote a memorial for the Northfield News on Jan. 30, 1975. He said, “One of the last times I saw Yosh I asked him which age group of students after working with senior high, college students, and junior high, he enjoyed the most. He seemed to feel that the senior high age group was the best. I am very grateful that he was able to end his career with the students he liked best.” Stoughton concluded a long tribute by saying that talk of creating a suitable memorial to Yosh would be “almost irrelevant, because the memorial is already there: the memories in the hearts of the many students whose lives he touched, and whose aspirations he strengthened.”

My thanks to those who shared their memories of Yosh Murakami with me and best wishes to the Murakami family: Mikiko and her husband Roy Sveinson in Manitoba, Paul and Suzanne Murakami in Edina, Rev. Steve and Betty Murakami in Sacramento, Jane Murakami in Fargo and Jon Murakami in Coral Springs, Fl. Molly Murakami, daughter of Paul and Suzanne Murakami, has followed her grandfather Yosh’s path and is a second-year studio art major at St. Olaf.