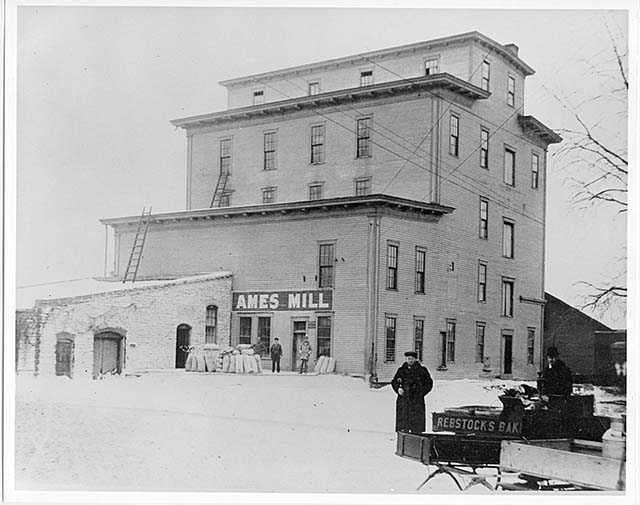

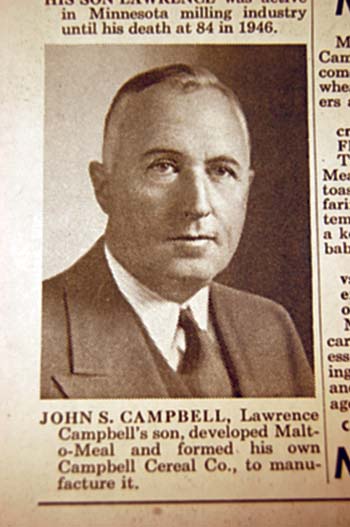

You won’t find too many interviews with John S. Campbell, who founded a company to produce the cereal known as Malt-O-Meal in Owatonna in 1919 and moved it to Northfield’s historic Ames Mill in 1927.

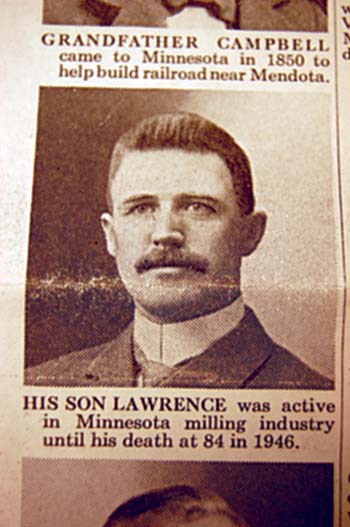

Campbell’s father, Lawrence G. (L.G.) Campbell, was equally as retiring when it came to personal exposure. The elder Campbell had been president and manager of milling companies in Blooming Prairie and Owatonna when he purchased Ames Mill in February of 1917 from the Ames family who had owned the mill since 1869. (The Ames Mill flour had received the “highest marking of any straight flour” at the International exposition in Philadelphia in September of 1876, at the very same time the James-Younger Gang was attempting to rob the First National Bank in Northfield.) L.G. Campbell’s aim was to use the mill for his trade name “Golden Palace” flour and cereal and he set about making a modern mill. The Northfield News of Nov. 30, 1917, said the old dam was being repaired and raised two feet, equipment had been ordered to double the capacity of the mill to 800 barrels and “wheels are whirring and sacks are being filled with the celebrated ‘Golden Palace’ flour and shipped out to feed a hungry world.”

The article then described L.G. Campbell as “the type of executive who gets results without raising much of a fuss about it and is modest to the extent that it has been impossible for the News man to find a photograph of him in existence or get him to take one in order to introduce him to our readers.”

Like father, like son? Perhaps. So it isn’t a surprise that I came across just one first-hand account of John S. Campbell to help introduce him to you. The story appeared in the Minneapolis Tribune of Sept. 21, 1969, when Campbell was 80 years old and talked to reporter Charles B. McFadden. Campbell was still chairman of the board and chief executive officer of Malt-O-Meal at this time, with his son-in-law Glenn Brooks serving as president since 1966. (Campbell retained his titles until his death at age 83 on Oct. 31, 1971.)

Campbell explained that after serving in the Army in World War I, he returned to Owatonna with $800 in amassed poker earnings, which he gambled on a “very unscientific development”: the blending of toasted malt with wheat farina to produce a new hot breakfast cereal. Campbell said, “My idea was to make a cereal that tasted better and cooked quicker than the top-selling wheat farina product, Cream of Wheat, which then took about 30 minutes to cook. Malt gave me the flavor I wanted and toasting reduced the cooking time of my finished product to two or three minutes.” He used an iron cylinder with a gas burner under it for equipment. He had once said that wheat farina was “flat tasting, like paper hanger paste,” and adding malt flakes to that breakfast staple was the key to what grew into his multi-million dollar enterprise.

Campbell was born in Austin, Minnesota, Oct. 20, 1888, and was a graduate of Blooming Prairie schools and Macalester College in St. Paul. His obituary in the Nov. 4, 1971, Northfield News, said that he had been commissioned in the infantry at Ft. Snelling in August of 1917 and served in Canal Zone, returning as a lieutenant to Owatonna in May of 1919. It was this year that he founded the Campbell Cereal Company to develop Malt-O-Meal, using an old creamery at 128 North Street as his first plant.

When Malt-O-Meal was celebrating its 75th anniversary in 1994, Campbell’s wife Isabel (who was then 97 years old) was asked by Northfield News writer Maggie Lee whether she had helped her husband “in his struggles to develop the then-revolutionary cereal.” Her response was, “Oh, no. He worked in a hole in the wall that he paid $11 a month for. He didn’t talk about the cereal. He wanted silence at breakfast so he could think. He didn’t even want the radio on.”

John S. Campbell told the Minneapolis Tribune in 1969, “At first I did everything myself. I did the processing, packaging and selling. I peddled the stuff to grocers in southern Minnesota. I soon found that any damn fool can make something but that it takes brains to sell it.” Donavon Pautzke, who started at Malt-O-Meal in 1967 and retired as senior vice president and director of manufacturing at the company in 1992, told me Campbell would arrange for young people to pass out samples door-to-door to build up demand. While sales increased to southern Minnesota and northern Iowa, it was still a slow go until 1922 when Parrot and Co. of San Francisco paid for a train carload to distribute to its own customers in the West. Pautzke also has heard that a boxcar carrying Malt-O-Meal to Texas went down off a washed-out rail trestle but the contents were able to be salvaged, saving the day for the company.

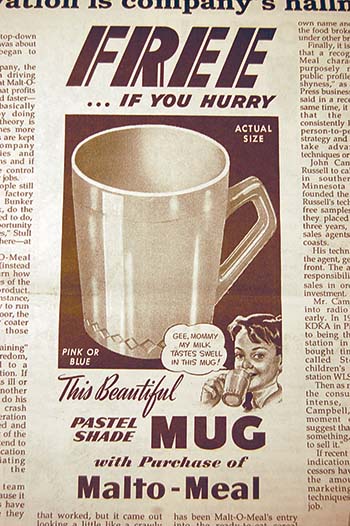

Then in 1925, Campbell ran ads for a planned two-week trial on WLS radio in Chicago. The Tribune story said, “The gimmick was to have listeners send in jokes with Malt-O-Meal box tops to ‘Steamboat Bill.’ If ‘Steamboat Bill’ read a joke on the air, the sender was given a toy steamboat. Malt-O-Meal already contained a toy steamboat whistle as a premium.”

According to Campbell, “Kids went wild. They would go to stores looking for Malt-O-Meal. The stores didn’t have it, but the pressure was on and they began ordering it.” The promotion went on for a year on WLS and in the Midwest, Southwest, far west and as far east as Pittsburgh, taking the company “right into the stratosphere,” said Campbell. Other successful radio promotions followed.

Needing to expand in 1925, Campbell moved the company into the old Simpson Mill of Owatonna which had once been operated by his father and an uncle. But soon even more room was needed. He looked toward the Ames Mill in Northfield which his father had sold in 1919 to Theobald Milling Co. of Cleveland, Ohio, but which had gone into bankruptcy just a couple years later.

The Northfield News announced “Breakfast Food to Be Made Here” on April 22, 1927, saying that operations of the Campbell Cereal Company “will be centered in the mill property that has been operated for the past year by L.G. Campbell.” Inducements to use Ames Mill were said to be trackage facilities and availability of water power. Automatic weighing, packing and sealing machines were being installed, “making possible a large volume production with a small force of employees.” John S. Campbell and his family came to live in Northfield that May, moving to Edina when corporate headquarters relocated to the Foshay Tower in Minneapolis at the end of 1935. (Headquarters are now in Lakeville.) Campbell engaged Joe Lucius as a millwright to install equipment and production lines and Lucius stayed on to run the manufacturing plant.

In 1932, a service station opened at the northwest corner of Ames Mill, run by Campbell’s Owatonna friend, Harold Starks. John Stull, who succeeded Pautzke as senior vice president of manufacturing, told me that one of the service bays inside was a parking spot for Campbell’s Packard, for which he had a driver employed by Malt-O-Meal. There were two bachelor farmers, called Dirty Dick and Filthy Frank (for obvious reasons), who paid their station bill once a year when they sold their crop. (“Not a good business model,” said Stull.) The station lasted until 1981.

Residents may remember that for decades there was a giant neon sign on top of Ames Mill. Pautzke said the leased sign would flash “Malt” then “O” then “Meal” and then the complete name would light up and repeat throughout the evening. It became a landmark and could be seen as far away as Dundas. But the sign did not comply with a city size ordinance for signs and Pautzke said he did not ask for a waiver. The sign was starting to deteriorate and, in Pautzke’s opinion, looked like it belonged on top of a brewery, not a wholesome cereal company. The sign was taken down in the early 1980s. (This month Northfielders can look forward to a lit-up Christmas tree design atop the mill.)

After World War II, sales nearly doubled for the company from 1948 to 1958. John S. Campbell introduced retirement profit sharing to the firm in the 1950s and in 1953 Campbell Cereal Company was renamed Malt-O-Meal, after its signature product. An April 22, 1954, Northfield Independent story said that 30 tons of breakfast food were made each day in Northfield, sometimes up to 42 tons, with machines making 165 boxes a minute. By 1961, chocolate flavored Malt-O-Meal had debuted.

And more good news: A front-page story of the Northfield News on Dec. 12, 1963, heralded the Malt-O-Meal purchase of the former plant of the Northfield Milk Products Company on West 5th Street (Highway 19) to “expand its operations into the ready-to-eat cereal field.” The story said Malt-O-Meal sales now covered 75 per cent of the country.

For a few years in the 1940s, the company had experimented with Campbell’s Corn Flakes, billed as a “summer cereal” counterpart to Malt-O-Meal, but World War II created a shortage of quality corn. Now Malt-O-Meal was ready to satisfy the public’s growing interest in convenience foods. By 1966, grain was being shot from guns inside cast iron cylinders to produce puffed wheat and puffed rice under the State Fair brand label. (Both Pautzke and Stull remember there was even an unsuccessful try at puffing pickles, but not for breakfast.) In 1967, the year Pautzke came from Del Monte to work at Malt-O-Meal, the company diversified to sell Soy Town snacks of roasted and salted soybeans in health food stores, Soy Ahoy in grocery stores and bought Profile Extrusion Company.

From 1969-1973, the company produced Malt-O-Meal Plus, a hot cereal with 100 per cent of the daily minimum requirements and, in 1970, acquired a competitor, Pophitt Cereal Co., with plants in Stockton, Ca., St. Louis and Minneapolis. The popcorn products of Pophitt’s Minneapolis plant were brought to the Campbell Mill when that plant closed a couple years later, so for a while Malt-O-Meal produced popcorn balls, some in the shape of bunnies at Easter time. Pautzke said the seasonal nature allowed the company to screen temporary workers for full-time employment. (The popcorn operation was sold in 1982.) In September of 1971, a month before John S. Campbell’s death, Malt-O-Meal was named Northfield’s Industry of the Year. The staff was now up to 70, with annual sales of more than five million dollars. But much greater fortune was on the way.

The acquisition of Pophitt had some fortuitous consequences for Malt-O-Meal, besides having taken over the bagged puffed wheat and rice cereals of a competitor. Pautzke said Pophitt “did some private labeling for grocery companies” and this gave Malt-O-Meal a toehold in the 1970s in that market. Soon Malt-O-Meal was making boxed cereal for chains including Super Valu, Kroger, Safeway, IGA, Waldbaums and Pantry Pride. Toasty O’s (think cheaper Cheerios) in polyethylene bags was introduced in 1975 and Sugar Puffs (sweetened puffed wheat) in 1980, contributing to a doubling of revenues between 1975 and 1980. (Pautzke said after making syrup for the popcorn operation, “It didn’t take a rocket scientist to think we could make sugar-coated wheat.”) Before Sugar Puffs was marketed nationwide in 1981, the company had consulted researchers at the Univ. of Minn. dental school who concluded that “if the cereal is consumed with milk for breakfast, the sugar-coated cereals do not increase the likelihood of cavities.” Pautzke said this testing was done to “satisfy our employees” as well as concerned customers.

The cascade of other cereal varieties which followed in the early 1980s included Raisin Bran, Corn Flakes, Crisp ’n Crackling Rice, Sugar Frosted Flakes and Honey & Nuts Toasty O’s, boosting revenues in 1985 to $50 million, with ready-to-eat accounting for two-thirds of sales, according to the International Directory of Company Histories. John Lettmann had become the third president and CEO of the company, the first executive not connected to the Campbell family. Tootie Fruities and Marshmallow Mateys debuted and a new 95,000 square foot distribution center opened in 1987.

Stull told me that when the company reached the $100 million milestone in 1990, the company paid for a day at Valley Fair Amusement Park for all employees. Then, in 1994, the company celebrated the 75th anniversary of its founding. According to a March 28, 1994, story by Dave Beal in the St. Paul Pioneer Press, the company now had 625 employees and a sales of $210 million in 1993 and 75 per cent of the bagged cereal market. Groundbreaking would take place for a three-year expansion which would more than double the plant size, bringing it to 860,000 square feet under one roof. The Ryt-Way property next to Campbell Mill had been acquired in 1989.

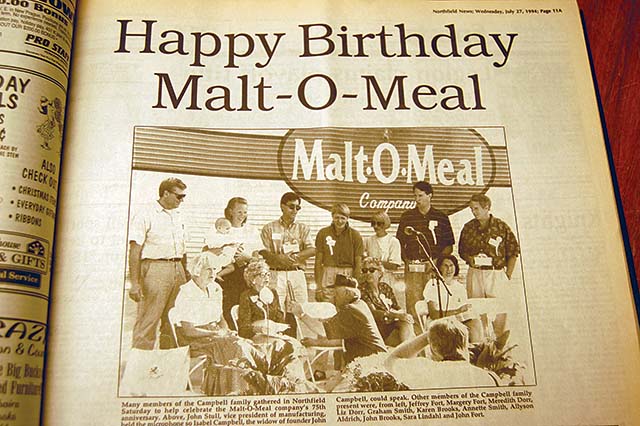

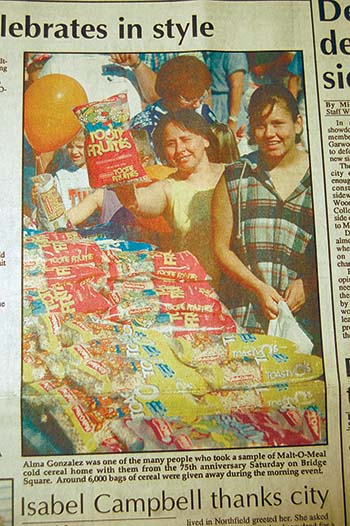

On July 23, 1994, Malt-O-Meal treated more than 5,000 people to breakfast on Bridge Square. Employees served hot and cold cereal, coffee, milk, fruit and Malt-O-Meal muffins made by Quality Bakery. The Troubadours, Community Band, Northfield Youth Choir and dancers provided entertainment. Mayor Marv Grundhoefer presented specially engraved cereal bowls to the Campbell family. The family, led by John S. Campbell’s 97-year-old wife, Isabel, thanked the community for its support and John Stull, in his capacity as vice president of manufacturing and emcee said, “We have the world’s most wholesome group of people assembled, right here in River City.” Excess foods were donated to the Laura Baker School and other non-profits that afternoon.

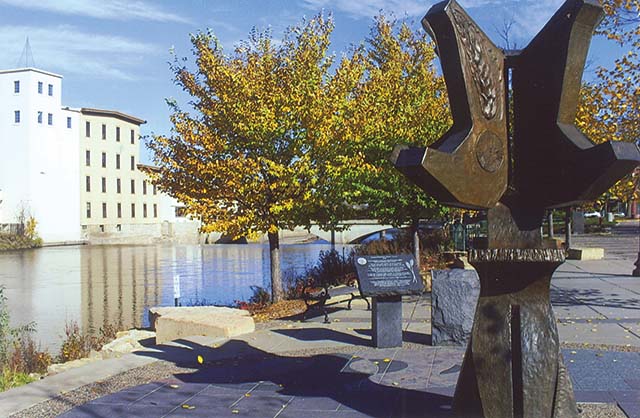

Also during this period, the Ames Mill was getting a facelift. Stull recalled that the asbestos siding had to be removed, as well as awnings which had “turned out to be a good roosting place for pigeons” and that were not appropriate to the history of the structure. The company elected to install redwood siding rather than less expensive vinyl and put in new Thermopane windows with “wood mullions in the style that showed in earlier photos of the mill building.”

In the late 1990s came another flurry of cereal offerings, including Berry Colossal Crunch, Honey Buzzers and Frosted Mini Spooners, Apple Zings and Cocoa Dyno-Bites and Fruity Dyno-Bites. Instant oatmeals, Toasted Cinnamon Twists and Honey Graham Squares were added in 2000, with a Malt-O-Meal original Balance with Berries (wheat flakes and freeze-dried strawberries) debuting in 2003. (Are you getting hungry for breakfast, at this point?).

One cereal you might have missed was introduced in 2007. Malt-O-Meal took part in a marketing campaign for The Simpsons Movie, making a limited run of Tootie Fruities sold in boxes marked KrustyO’s, which was sold in 7-Eleven stores (recast as Kwik-E-Marts) in a dozen cities, but none in Minnesota.

Chris Neugent, who became the fourth CEO in 2008, presided over further company progress. Malt-O-Meal with its ready-to-eat cereals was named “one of America’s hottest brands” of 2011 by Advertising Age Magazine which praised the company for passing on savings on advertising to the consumer and for reducing packaging and aiding the environment by bagging instead of bagging within a box. Stull told me that using bags to save money for families was the “basis for the success of the company,” even though Malt-O-Meal does make boxed cereal, as well.

Malt-O-Meal was renamed Mom Brands in 2012 to reflect its many other products, with sales having reaching about $750 million the previous year.

In February of 2012, the Malt-O-Meal Company took the name MOM Brands to indicate the range of its products, while keeping its historic abbreviation. A Star Tribune story on June 13, 2012, reported that between 2001 and 2011 annual sales had climbed from about $300 million to about $750 million and about $100 million had been spent in the past decade “boosting production capacity and efficiency” in Northfield. Ready-to-eat cereals were dominant, with hot cereal only 10 per cent of total sales now and private label cereals at 20 per cent.

Northfield has the largest of manufacturing plants which are located also in Tremonton, Utah, Asheboro, North Carolina and St. Ansgar, Iowa. The company is second only to St. Olaf College as Northfield’s largest employer (MOM Brands has 716 employees here, including the distribution center, and St. Olaf has 890 full and part-time employees).

Stull said, “Malt-O-Meal’s niche in the marketplace was to make very good cereals just like the big companies did, but to keep the overhead low in the company,” including doing less marketing. The company’s website, mombrands.com, has videos in which Second City improvisational theater members stage real focus groups to try to convince them a cartoon character like Sally the Squirrel or hoopla (a consumer is pelted with confetti as he samples a cereal) can make a cereal taste better. (Spoiler alert: The consumers don’t fall for it.)

Stull said, “Malt-O-Meal’s niche in the marketplace was to make very good cereals just like the big companies did, but to keep the overhead low in the company,” including doing less marketing. The company’s website, mombrands.com, has videos in which Second City improvisational theater members stage real focus groups to try to convince them a cartoon character like Sally the Squirrel or hoopla (a consumer is pelted with confetti as he samples a cereal) can make a cereal taste better. (Spoiler alert: The consumers don’t fall for it.)

Stull told me that Donavon Pautzke and the late company president Glenn Brooks led by example, providing “enlightened leadership” that was “not dictatorial.” A concept of cross training was developed where employees got to know the whole production line and shared responsibilities, “getting people involved all the way around,” in Pautzke’s words. Stull said it was better to have people who were part of a team, sharing responsibilities, “taking the raw materials, cooking it, forming it, shaping it, packaging it and shipping it out the door” so that “it was their product and they owned it.” The company would pay for any classes taken by employees. (Pautzke remembered bringing in a St. Olaf professor to teach statistical analysis and Stull recalled an accounting class on St. Olaf’s campus held for Malt-O-Meal employees.)

Malt-O-Meal has traditionally been a good place to work, with turnover as little as one per cent a year. Stull remembered there was a new production line needing 50 employees, and 1,500 people showed up to apply. Stull, who started out loading boxcars here in 1970 after being laid off as a pilot and rose through the ranks, credits the “good strong work ethic” of the employees of what is billed as the largest family-owned cereal company.

Pautzke told me, “People are the most important resource we had. You can buy equipment, that’s easy. You can buy a million dollars worth of building, but you can’t really make it run unless you have competent people doing it.”

There is a story that when John S. Campbell was learning to throw a curve ball while throwing a baseball at a target, his grandfather protested, “That’s not fair to the batter!” Such principles were said to have inspired Campbell. At any rate, Campbell very much valued the company he founded. At the end of the rare interview he gave in 1969, Campbell told the reporter he had had offers to sell his company but was not interested. Gesturing to a painting of the Malt-O-Meal plant in Northfield, he said, “I’d rather have a living thing like that than a piece of paper.”

When the wind blows whiffs of one of the fragrant cereals being produced here through the town, Northfield residents are indeed grateful that Campbell moved here from Owatonna in 1927.

Thanks to the Northfield Historical Society and the Steele County Historical Society for research assistance.