Today’s Carleton College students know the names Fred B. and Deborah Sayles Hill. That is to say, they know the names Sayles and Hill as they meet and mingle in the Sayles-Hill Campus Center which contains the post office, career center, bookstore, radio station, snack bar, pool tables, student publication offices, a computer lab and other campus services. Some of yesterday’s students remember when this building was a gymnasium and may recall, as many Carls, Oles and some townies do, going to dances there. But few have heard about the love story which led to this building and which sparked other beneficent acts in Northfield.

The building was formally dedicated as Sayles-Hill Gymnasium on Jan. 26, 1910. It was presented to the college by Fred B. Hill and his wife Deborah Sayles Hill, who had provided close to $63,000 for its construction. Their first donation of $35,000 had been announced at a chapel service at Carleton the year before. The Northfield News of Jan. 23, 1909, wrote that students “fairly bubbled over with enthusiasm and could not contain themselves” as they “marched downtown and paraded about mill square,” yelling and cheering.

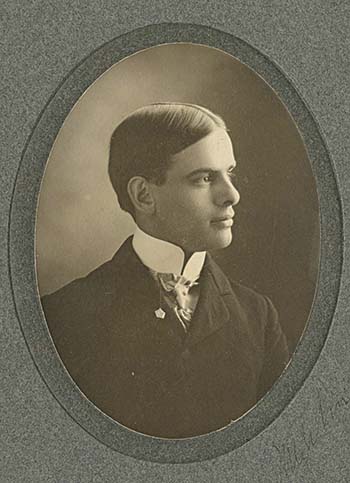

An outsider might have been surprised at the magnitude of this gift because Fred B. Hill was a religion professor at Carleton at a time when professors did not have salaries that enabled them to construct monumental buildings. (I’ve been told this may still be true.) And Fred Burnett Hill (born May 15, 1876, to Red Wing, Minn., pioneers Edwin Frederick Hill and Grace Jeannette Squire Hill) was not related to the wealthy James J. Hill, railroad magnate.

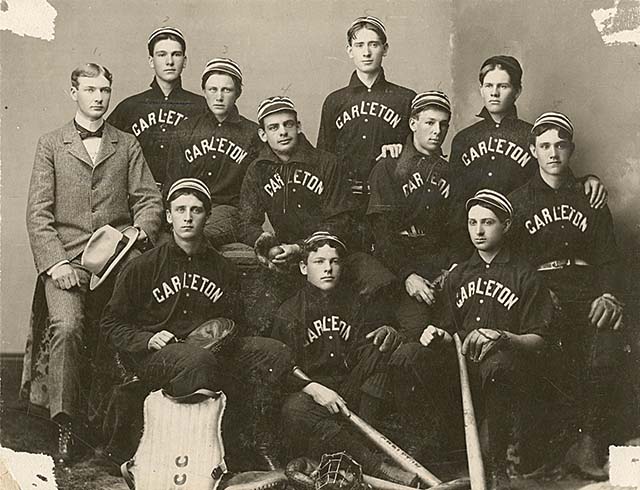

Fred Hill was a graduate of Morris High School in 1895. Having spent the previous school year in Carleton Academy (the preparatory school which was discontinued in 1906), Hill returned to Carleton and worked his way through college as a member of the class of 1900, earning a bachelor of literature degree. He was also a star left-handed pitcher for Carleton’s baseball team and maintained a keen interest in sports throughout his life. He was also noted as a speaker, his declamation at an Adelphic Literary Society exhibition having been delivered “with a voice and manner that held the audience perfectly and at times almost breathless,” according to the Northfield News of March 18, 1899.

Hill went east after graduation, earning a bachelor of divinity degree in 1903 from Hartford Theological Seminary in Connecticut and becoming ordained in the Congregational Church. He served as pastor of the Central Congregational Church of Providence, Rhode Island, from 1903 to 1905 and it was there he met Deborah Wilcox Sayles. This was a life-changing event not only for them but also for the town of Northfield where they settled after their marriage.

As described in Craig Smith’s 2007 biography of their daughter, Jenny Vincent (see sidebar), Deborah Wilcox Sayles could trace her lineage through her father Frederick Clark Sayles to Rhode Island’s founder, Roger Williams. A few years after her father’s marriage to Deborah Cook Wilcox in 1861, he became partners with his brother William F. Sayles in a finishing plant and bleachery. Smith wrote: “Over the next three decades the Sayles brothers expanded into railroads, mills, and utilities, amassing a fortune estimated at $20 million. Frederick also served as Pawtucket’s first mayor.” Frederick and his wife passed on “their political conservatism, appreciation of the arts, and sense of community responsibility to their children, including Jenny’s mother.”

Deborah Sayles was born Nov. 17, 1880, and Smith wrote that she “grew up the belle of Bryn Mawr, her family’s 65-acre estate. She could sit on the front steps of a red brick mansion that was filled with paintings and sculpture from Europe and look over cultivated gardens, grounds and greenhouses. She appeared to want for nothing.” Unfortunately, she suffered two blows when her mother died in 1895 and her father died on Jan. 5, 1903. He was able to dedicate a building for a public library as a memorial to his wife in Pawtucket on Oct. 15 the previous year, despite having suffered a stroke.

Smith wrote that “Deborah was no stranger to suitors, several reputedly among European royalty, but the only one she took seriously was a Yale University student from Illinois named Frank Ferry. However, Frank could not dislodge Fred. The engagement drew storybook headlines from the society pages: ‘Beautiful Heiress Spurns Rich Suitors; to Wed Poor Pastor.’” Smith noted that, while it was a love match, it also “demonstrated her independence of mind and determination not to become just another wealthy matron.” Deborah said, “My future is not in society. I am tired of the ballrooms, the idle talk the butterflies, the aimless lives. I want an opportunity to relieve suffering and support and encourage the work of uplifting humanity.”

In the Carleton College archives is a letter that Hill had written to his classmates on Nov. 19, 1905, from Dresden, Germany. Hill said: “Well last November 21st I became engaged to miss Deborah Sayles of Providence – the event was duly announced on Nov. 30 and last June 14 we were married in Providence in the church of which I had been the assistant minister for two years. The affair was very pleasant and went off without a hitch…We had a great number of presents and felt extremely grateful to the many friends who remembered us.” The couple was honeymooning in Europe and Asia, visiting tourists sites as well as missions along their way.

In 1906, Fred started a year of post-graduate work at Hartford Theological Seminary and Mary, the first of five children, was born. In 1907, Hill accepted an offer to be a professor of Biblical literature at Carleton and a minister in the Congregational Church of Northfield.

Hill is described as one of Carleton’s “best-beloved and most influential teachers” in Carleton: The First Century (1966) by Leal A. Headley and Merrill E. Jarchow: “At the age of 27, he assumed with characteristic vigor not only the chairmanship of the department but also leadership in social and athletic activities on the campus. Few teachers in Carleton history have approached him in winning the admiring affection of both students and faculty colleagues.”

Hill spoke up on behalf of Carleton very early on. As chairman of a faculty committee on athletics during his first term at Carleton, Hill explained in a Northfield News story of Dec. 28, 1907, about a rift with St. Thomas of St. Paul. St. Thomas had won that year’s football game against Carleton 5-0, with “unsportsmanlike conduct.” The St. Thomas manager had insisted on an official who was said to be a “Hamline man,” but wasn’t, and his decisions were “so bad that even men who had no interest in the outcome, save as they desired fair play, threatened to help mob him.” The St. Thomas manager also insisted on using a St. Thomas man as head linesman. This partisan official gave St. Thomas four downs twice in succession, resulting in the only score of the game. Hill said, “Carleton doesn’t beef because of defeat…But in this instance St. Thomas used tactics which are common with her, and it was this which brought forth the resolution severing connections.”

Within just a few years of the Hills’ arrival in town, Carleton was celebrating their largesse. On Jan. 26, 1910, the new Sayles-Hill Gymnasium with its basketball floor, swimming pool, running track, trophy room and social and recreation rooms was dedicated in honor of Professor Hill’s mother and his wife Deborah’s parents, all expenses paid by the couple. In his dedicatory address, Hill hoped that the building “may ever encourage and foster stalwart, virile and Christlike manhood among the students of Carleton College.” (The female athletes would have to wait for the Elizabeth Cowling Recreation Center for Women, formally dedicated on May 14, 1965.)

Sayles-Hill was a boon to the development of the sports of swimming, indoor track, gymnastics and especially basketball. Carleton won the first official game of basketball played at the gym, defeating Pillsbury Academy 27-11 on Jan. 22, 1910. Carleton lost its first game to cross-town rival St. Olaf on Feb. 5 by a score of 22-8.

In 1913, Hill and Maurice Kent, director of athletics, invited 14 Minnesota high school basketball teams with the best records to a play in a tournament April 3-5 in Sayles-Hill Gymnasium. This very first state high school basketball tournament was won by Fosston over Mountain Lake 29 to 27. In 1923, the tournament was moved to the Twin Cities to accommodate larger crowds.

The Sept. 12, 1913, Northfield News reported that Hill stepped in to buy the old Ames Mill and adjacent property. The story said, “Professor Hill’s public spirited act has safeguarded the best interests of the city against speculators who might otherwise have acquired control of this property. He proposes to hold it in trust until such time as the city see fit to buy it for public purposes.”

The new Georgian Revival Style residence of the Hill family across from Central Park was built to resemble Deborah’s much larger childhood home. Jones had already designed a Dutch-Flemish Revival complex for the Odd Fellows on Forest Avenue (dedicated in 1900), an English Tudor home at 613 E. 4th St. for Watts William Pye in 1905 and the Egyptian Revival State Bank Building in 1910 (now the law office of Hvistendahl, Moersch, Dorsey and Hahn at 311 Water St. S.). The Methodist Church purchased the Hill mansion in 1921 and moved their church building to the house’s east lawn, using the house as a parish house for church activities. Carleton attained the property in 1965 and the old church was torn down in 1966. Except for one year, the mansion has been used to house students and, as of the 2014-2015 school year, it has been designated the “Parish International House,” a home to students interested in foreign languages and cultures, and “a place for all students who share a passion for learning about other parts of the world.”

In May of 1917, Hill was elected president of the Northfield Commercial Club, soon renamed the Community Club, and forerunner of the Chamber of Commerce. Under consideration were plans to remodel the former YMCA Building (today the home of the Northfield Arts Guild at 304 Division St.) for use as a community building and city hall. The Northfield News reported on March 22, 1918, that, in a “complete surprise,” the Hills had agreed to add $5,000 to their previous pledge of $1,000 to make this much-needed project happen, if the Community Club raised $4,000.

Deborah Hill gave freely of her time and money to Carleton and charitable causes, including the Northfield chapter of the Red Cross, of which she was elected secretary in 1917. Fred was president of the Hospital Association, a member of the school board and led many volunteer organizations. In July of 1918, Hill (who had been leading local war bond drives to help pay for costs of U.S. involvement in World War I) was named member of the “war work council” of the YMCA and was sent overseas on a special commission to visit and assess needs at soldier training camps in France. Upon his return from Europe late in September, Hill threw himself into a grueling schedule of giving speeches throughout the Northwest about relief efforts, while still carrying a teaching load. In November he was the Minnesota YMCA representative at a meeting in Chicago.

About 3 a.m. on Nov. 11, 1918, fire bells rang in Northfield to announce the end of World War I, the so-called “war to end all wars.” Hill gave an address at Carleton’s Skinner Memorial Chapter on Armistice Day but ended up fighting a battle against an enemy that took more than twice the lives worldwide than World War I had. The Spanish flu had led to a quarantine at Northfield’s two colleges which was lifted in January of 1919. But five people died in Northfield: four St. Olaf students and Fred B. Hill of Carleton.

The Northfield News of Jan. 31, 1919, said, “Nothing has thrown such a pall over the entire community in many a day as the sad news which spread rapidly Wednesday evening that Fred Hill was dead, a victim of the dread and treacherous influenza-pneumonia.” On Jan. 17, Hill ran a high fever which worsened within a week as pneumonia developed in his lungs. A transfusion of blood was a “final effort to rally the patient’s forces,” but “his hard work during the past months had sapped his system of its reserve strength” and he died on Jan. 29. He was only 42 years old. The story said, “The college and community were greatly shocked by the news of Mr. Hill’s death, for it was generally understood that he was out of danger. When the news was given out during the intermission between the first and second games between Carleton and St. Olaf basketball teams, a great pall seemed to hang over the audience. The second game was postponed out of respect for Mr. Hill and Carleton.” The only bright spot: the four youngest Hill children who had been ill with influenza were improving and “out of danger.”

On Feb. 16, Carleton College and the community of Northfield held a memorial service for Hill in Skinner Memorial Chapel. A Carleton College News Bulletin contained many memorials, including one from Carleton’s president, Donald J. Cowling, who said Hill “found his chief joy not in the holding of the things he had, but in the gratitude of those he helped.” In that same spirit, Deborah Hill gave $50,000 to endow the Fred B. Hill Foundation at Carleton.

The Northfield News of June 4, 1920, reported the departure of Deborah Hill and her family for summer travels and then to make their home in Winnetka, Illinois. The story said, “During the years of her residence in Northfield, Mrs. Hill has taken a strong hold upon the hearts of the people of Northfield and it is with sincere regret that they come to realize that she will not return in the fall to be with them again.” Their wish was to “assure her that she can never go beyond the love and esteem in which she is held here in Northfield.” Three of the Hills’ five children returned to attend their father’s alma mater, Carleton.

In 1920, Deborah married Frank F. Ferry of Winnetka, an executive of a Chicago business firm who had been one of her wealthy suitors. Their son, Frank F. Ferry, Jr., was a member of Carleton’s class of 1943. Deborah’s second husband died in 1948 and Deborah Sayles Ferry died Sept. 16, 1953, at the age of 72, in Prairie View, Illinois.

When Fred Hill died in 1919, J. Arthur Hughes, who was a member of the Carleton Class of 1919, contributed to the memorials. He said: “Though future generations of Carleton students may never know save in the vaguest way of Professor Hill’s influence, yet that influence will so have embodied itself in the hearts of Carleton students, will so have moulded Carleton’s traditions and modes of thought, that this rich blessing of a life well spent will still be a potent force in Carleton’s history.”

At least as long as Sayles-Hill Campus Center exists, the family names of Fred B. Hill and Deborah Sayles Hill will be remembered and preserved.

Thanks to Eric Hillemann of the Carleton College Archives and Craig Smith, Jenny Vincent’s biographer, for assistance with this story.

Jenny Hill Vincent, Still Singing

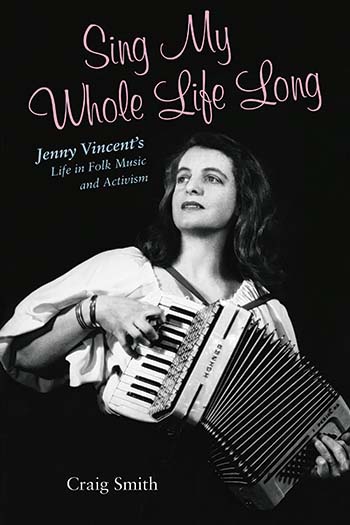

Mexico. Craig Smith wrote this biography of her life in 2007. Book cover with photo from 1947 courtesy of Jenny Vincent and the University of New Mexico Press.

In a diary entry dated April 4, 1917, Deborah Sayles Hill wrote that her “darling, sweet little Jeannette,” about to turn four, was “pretty, winsome, healthy and attractive in every way. Golden curls and pink cheeks and a fine little singer.”

Jenny Vincent, born in Northfield in 1913 to Fred B. Hill and Deborah Sayles Hill, went on to make a name for herself as a prominent folk singer and activist in New Mexico. Craig Smith wrote this biography of her life in 2007. Book cover with photo from 1947 courtesy of Jenny Vincent and the University of New Mexico Press.

Deborah Jeannette Hill, called Jenny, was the fifth child born to Carleton professor Fred B. Hill and Deborah Sayles Hill on April 22, 1913, in Northfield. Craig Smith, Jenny’s biographer, wrote in Sing My Whole Life Long: Jenny Vincent’s Life in Folk Music and Activism (2007) that Jenny’s mother Deborah was an accomplished pianist and Jenny “began to crawl up beside her on the piano bench” to imitate her. Jenny’s early musical taste was influenced by her mother’s classical repertoire and popular songs learned from college students.

When she was only five, Jenny’s father died of complications from the Spanish flu, just months after the Armistice of Nov. 11, 1918. Smith wrote that “to this day the peal of bells can send her mind back to the memory of an international celebration of peace, a time of joy that became tragically merged with a personal and premature loss.”

Deborah, a widow at 39 with five young children, moved to Winnetka, Illinois, where, in July of 1920, she married a former suitor, Frank F. Ferry. The combined wealth of the Sayles and Ferry families created a privileged upbringing for Jenny. She continued the piano lessons she had begun in Northfield and by 7th grade she could play anything by ear. In 1926, she was enrolled in the North Country Day School in Winnetka, a progressive school where she was exposed to the folk music of the world which became an abiding love.

Jenny majored in piano and composition at Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, N.Y., and after graduation in 1934 married her high school sweetheart, Harry K. “Dan” Wells. Pursuing an interest in D.H. Lawrence, the couple bicycled around Germany and England to places the writer had been. Through a meeting with the sister of Lawrence’s widow, they were invited to visit Frieda Lawrence in San Cristobal, New Mexico, near Taos, in the summer of 1936.

Dan and Jenny Wells were so impressed with the area that in 1937 they bought a deserted, 40-acre ranch for $2,500. In 1940, they moved permanently to New Mexico, rebuilt a road with neighbors, restored the ranch and started a summer camp and a school. The ranch also provided a gathering spot for musicians, writers and others. Jenny became Taos County educational director for the Rocky Mountain Farmers Union in 1943.

Jenny entertained veterans in hospitals in New York in 1945 as part of the American Theatre Wing War Service and allied herself with singers and social rights activists such as Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie and Malvina Reynolds. In 1948, she accompanied Paul Robeson on piano at a Progressive Party rally in Boulder, Colorado, and performed at the party nominating convention with Seeger in Philadelphia.

In January of 1949, having divorced Wells in 1947, Jenny married Craig Vincent, a political activist in the Denver area. They reopened the San Cristobal ranch as a guest home and Jenny continued her efforts to preserve Spanish language folk songs in the Southwest. In the 1940s, when use of Spanish was forbidden in New Mexico classrooms, she came into the schools with guitar and accordion to teach Spanish songs.

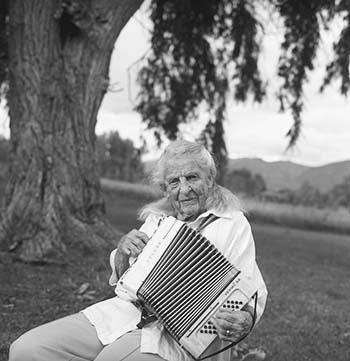

Jenny founded the Cantemos Records label and Taos Recordings and Publications to record local music. From 1956 to 1986, she performed with Nat Flores and Hattie Trujillo in the popular group Trio de Taos and, in 1998, formed the Jenny Vincent Trio with Rick Klein and Audrey Davis, playing with them into her 90s.

Vincent is shown here outside her home in San Cristobal, New Mexico, in 2006. In 2013, at the age of 100, she was given the New Mexico Governor’s Award for Excellence in the Arts. Photo by Dorie Hagler, courtesy of the photographer and the University of New Mexico Press.

Jenny made one last trip back to her birthplace of Northfield in 1981 when she was attending an American Folklore Society Conference in Minneapolis. She visited her father Fred Hill’s grave at Oaklawn Cemetery.

In 2013, at the age of 100, she was given the New Mexico Governor’s Award for Excellence in the Arts, honored as “one of the greatest folk musicians in New Mexico” who used music “to remove barriers between people of different cultures.”

In a recent e-mail, Jenny’s biographer, Craig Smith, wrote, “Jenny is alive and well and living in the Taos Retirement Village. Every Tuesday morning a group of us go there to play music with her. She no longer has the strength to play the accordion, but continues to play the piano beautifully.”