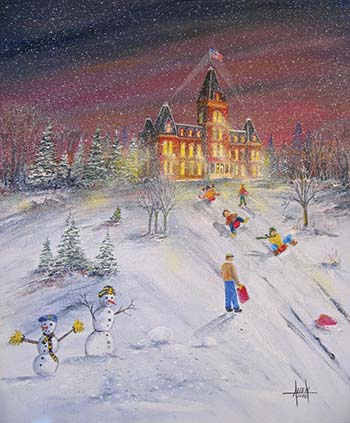

No one that I knew when I attended St. Olaf in the 1960s brought sleds with them to college. They found there was no need to, when you could “borrow” a tray from the cafeteria and slide down the hill behind Old Main that way when snow fell. Years later when I lived in New York and would visit Northfield to see family who had settled here, my daughter joined her cousins on actual sleds on that same hill, in the type of scene captured so charmingly by Northfield artist David Allen.

The old joke is that the four seasons of Minnesota are “almost winter, winter, still winter and road construction.” Now that we are in January’s cold grip, we might as well celebrate winter. So, here are reminders of a few winter activities from past years.

Riding toboggans was popular (and healthful), according to St. Olaf College’s January-February Manitou Messenger of 1887. New toboggans had come and the school paper reported that “coasting is the principal amusement nowadays, and boys and girls ought to be out and try to slide away rheumatism and every other illness.” A sliding route had been prepared and several toboggans “have been in constant service” in this “extremely entertaining sport.” There were dangers: “The boys are talking about getting a a cow-catcher on the toboggans. They say some one will get run over before long if they do not get them.” The prophecy came true, as the school paper reported that a toboggan “struck a lady and sent her flying about a rod away.” Undeterred, the boy who steered the toboggan said he thought he did quite well, “as it was the first time he had ever tried to steer.” Another time, three boys on board a toboggan were hurt when it went against a tree: “One twisted his arm, another hurt his leg, and the third struck a big hole in his head in which he has carried a bale of cotton ever since.”

Across the Cannon River at Carleton College in that January of 1887, the Carletonia said, “The old winter recreation of sliding down hill on a sled is a thing of the past, having been replaced by the lately imported Canadian sport of tobogganing.” The writer declared, “Tobogganing will henceforth form a great part of our winter recreation.” The story noted, “Considerable nerve is required in order that one may fully enjoy the sport, especially at the start, but the danger the novice imagines generally changes, after the first slide, to the greatest enthusiasm. It is a sport which both old and young may practice and enjoy.” In addition, those who “confine themselves to the ofttimes over-heated study-room” would profit from the exercise in walking back to the head of the slide.

This Carletonia article mentioned the opening of the “Northfield Winter Carnival and Toboggan Slide” on Jan. 15. The slide was located at the head of First Street, with a shoot of 170 feet and a drop of 90 feet. “The entire length of the slide was illuminated by torches giving it all a very gay and Carnival-like appearance…Each toboggan was crowded to its utmost capacity, and, as it started down, the occupants would give a rousing cheer – the more the merrier.” As riders “launched out and shot like a meteor down the icy track,” many were heard to “bid their friends good-bye, for they knew they should surely be killed.” But, when the toboggan stopped, they invariably said, “O, let’s go again!” The account ended, “It is about the only winter sport we have, and we advise all to take advantage of it.”

The Northfield News of Jan. 15, 1887, said that C.A. Drew of the Acme Toboggan Club was the first man to test out the slide earlier in the week when he lost his balance and flew down the slope on his rear end, plunging into a snowdrift. The paper joked that the St. Paul Winter Carnival was negotiating to have him give an exhibition.

Years later, on Jan. 31, 1911, Carleton’s paper touted a sophomore club’s achievement of having “hair-raising joy rides on St. Olaf’s coasting hill” in its red custom-made pine lumber “bob” coaster – two feet wide, 18 inches high and 18 feet long. The “Red Imp,” as it was named, had a large steering wheel and a gas-fed automobile headlight and had made a record run of a half-mile.

In February of 1910, a Winter Sports Club had been organized at St. Olaf which led to a new coasting road and the purchase of bobsleds which the Viking yearbook for 1910-12 described as being from 12 to 16 feet long and accommodating up to 18 passengers on each. “The sleds tear down the road at the rate of 50 miles an hour and finally come to a stop about three city blocks below the foot of the hill,” the yearbook said. The sleds were brought back up by horses.

At the end of 1910, a 25-foot wooden ski scaffold was erected on the hill behind present-day Thorson Hall and was dedicated in January of 1911. St. Olaf College Associate Archivist Jeff M. Sauve wrote on the website northfieldhistorical.org that this ski jump led to St. Olaf being one of the first U.S. colleges to offer ski jumping as a sport. There were annual tournaments, attracting skiers from the northwestern U.S., Norway, Ireland and Italy, with 1,500 or more spectators. The first one was held in January of 1912 when world champion Anders Haugen and his brother, Lars (who held the national championship), came voluntarily with members of the North Star Ski Club of Chippewa Falls, Wis., to help introduce the sport to American colleges. Anders Haugen, who won four national ski jumping championships and was the first American to win an Olympic medal in the sport, then helped upgrade to a new steel ski scaffold, which was 75 feet high with a run of 190 feet, according to the Northfield News of Jan. 4, 1913. This structure was named after Anders Haugen and dedicated prior to the Jan. 13, 1913, tournament, when amateurs competed and professional record-holders Oscar Gunderson and Anders and Lars Haugen gave exhibitions. The Northfield News of Jan. 18 reported that the “ski-men” made some “thrilling jumps and at times some equally thrilling rolls down the steep hill.”

Sauve also wrote of what happened at this location during the 1946 groundbreaking for Thorson Hall: “Officials and spectators were horrified to see a body hurtle from the top of the slide and plunk to the ground below. Pandemonium ensued as the crowd rushed to the scene. An ambulance was summoned and arrived quickly with siren screaming. All this help was for a dummy, fashioned and tossed off the slide by prankster students.” Sauve said that the ski jump was removed for safety reasons in 1961. A picture of the slide posted in “Old Northfield” on Facebook brought forth memories from several who had climbed the aging structure as adventurous youngsters (one of whom wrote she had been terrified). There is a color video of the St. Olaf Ski Jump, circa 1950, at northfieldhistorical.org/items/show/15, courtesy of the St. Olaf College Archives.

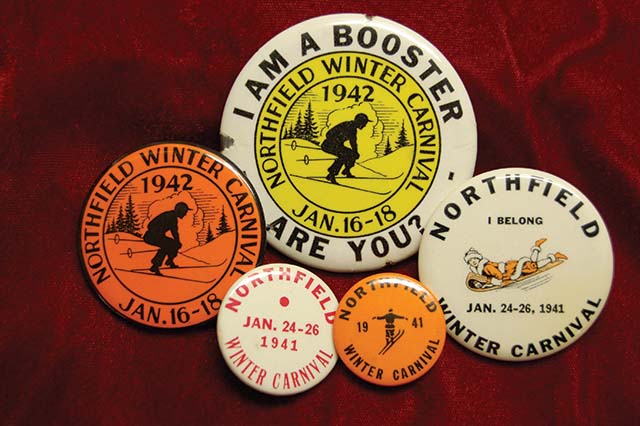

Northfield’s first Winter Carnival in January of 1941 was preceded by a visit on Jan. 12 from the royalty of the 1941 St. Paul Winter Carnival with an entourage of two trainloads of about 1,500 people, including ten drum and bugle corps, bands and other marching units promoting their event in a parade. The trains continued on to Faribault that afternoon, leaving columnist W.F. Schilling to grumble that “the horses were not taken off the train at Northfield but were held back for observance by our big sister city down the line where many of the urbanites had never seen a mounted horse.”

Northfield’s 1941 Carnival took place Jan. 24-26, starting with a basketball game between Northfield and Faribault in which Northfield avenged an earlier last-minute defeat with a one-point win. King North I, William Revier, and his queen, Lucille Elstad, were crowned after the game, with a coronation ball following at the Armory. Saturday’s events included speed skating races, cross-country and downhill ski races, dog sled races, hockey games, an amateur show at the NHS auditorium and a “Big Carnival Dance” at the Armory. The Dog Derby was held above the Fifth Street bridge Saturday afternoon on the Cannon River. There were four entries and four prizes, thus satisfying all the contestants, said the Northfield News on Jan. 30, adding: “The boys and their dogs had a lot of fun, as did the rumored 15,000 spectators who watched the race. With the schools so full of husky young boys and so many dogs roaming the streets of Northfield, it seems too bad that there couldn’t have been a larger registration for this event.” An ice palace on Bridge Square, illuminated by electric lights at night, “formed a pleasing spectacle,” according to the Northfield Independent of Jan. 30. There was a snow sculpturing contest and the skating races were held on the city skating rink on the river, which was also open for community skating. (By the way, I have never seen anyone skating on the Cannon River, so this appears to be a pastime which has passed.) The hills on the Carleton campus were available for skiing and tobogganing, while the competitive downhill and cross country skiing events were held at Heath Creek Saturday afternoon.

There were two parades on Sunday. The first featured floats, the Northfield High School band, service clubs and marching clubs and drum and bugle corps which had come down in a special train from St. Paul. An Ice Revue featured 50 members of the St. Paul Figure Skating Club performing just above the dam on the Cannon River. The Northfield Independent reported on Jan. 30 that spectators crowded onto the ice and lined the banks of the river in bright sunshine as the club put on a “beautiful and clever performance” which was “greatly enjoyed.”

Another group of St. Paul Winter Carnival boosters paraded in Northfield in the evening, on their way back to St. Paul after train stops in Owatonna, Albert Lea and Austin. Estimated attendance at Sunday events was 10,000. A group of Northfielders planned to participate on horseback in “Jesse James attire” in a St. Paul Winter Carnival parade “to reciprocate in a small way for the many paraders who came from St. Paul to help make Northfield’s winter carnival a success,” according to a Jan. 30 Northfield News story.

Early in the week of Northfield’s first Winter Carnival, Northfield had a special visitor: Joe DiMaggio. DiMaggio had arrived in town on Sunday, Jan. 19, with his wife, Dorothy Arnold. Arnold, a Duluth native, was an actress whose sister, Leone, lived in Northfield. The legendary Yankee baseball player was introduced the next day at a Northfield Lions Club luncheon by his brother-in-law, Orville Dahl, and the Northfield Independent of Jan. 23, 1941, reported, “Joe, in his modest and unassuming manner, took a gracious bow and generously autographed baseballs and cards for the fans present” and then, after the luncheon, “an informal group gathered around Joe DiMaggio and talked baseball.” They also saw a program presented by Dr. Frederick A. Heiberg (father of current Northfield resident, Dr. Elvin Heiberg) of color movies of a recent trip to the East Coast and of the Jan. 12 parade.

The Independent wrote, “This is Mr. DiMaggio’s first experience with a northern winter, and he claims he likes it.” DiMaggio visited St. Olaf, since Leone Dahl had worked as an assistant at the college library and Orville Dahl was assistant dean of men and an English instructor there. (DiMaggio started his famous 56-game hitting streak on May 15, 1941, about four months after his visit to Northfield. His marriage to Dorothy Arnold was over by 1944; in 1954 he married another actress, Marilyn Monroe.)

The first Northfield Winter Carnival was a financial success, with a small surplus for the next year’s carnival. The second annual Winter Carnival which was held Jan. 16-18, 1942, was less fortunate. A January thaw led to cancellation of a planned ice palace and a figure skating show of touring international skaters. A big float, in the form of an ice palace, was used instead on Bridge Square. The Friday carnival dance went on as planned at the Armory, with the coronation of “Northfield’s genial postmaster,” Carl C. Heibel (father of current Northfield resident Dick Heibel), as King North II and Carleton senior Virginia Millis as Queen, both wearing royal purple velvet costumes and crowns of gold. But since almost all the snow had disappeared, Saturday’s winter sports events and Sunday’s skating events were cancelled. A Sunday parade provided cheer, with spirited representatives of the St. Paul Winter Carnival, including several drum and bugle corps, marching units and King Boreas.

The two-year Winter Carnival tradition in Northfield ended as the widening of World War II put a damper on such celebrations. But, of course, another yearly tradition, with its own parade, was on the horizon: The first September townwide celebration of the 1876 defeat of the James-Younger Gang was held in 1948.

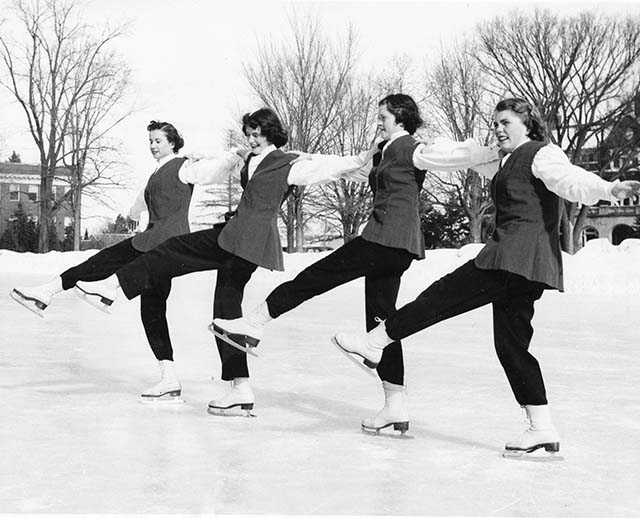

In preparation for this column, I looked through many images at the Carleton College Archives and chose a few to illustrate winter pastimes there. I ran across a chorus line photo from the “Circapades,” an ice show with the theme “The Greatest Snow on Earth,” part of Carleton’s winter carnival of Feb. 20-21, 1953, sponsored by the sophomore class.

The carnival featured a hockey game versus St. Cloud on the Bald Spot, followed by another hockey contest between college waiters and waitresses which the Carletonian of Feb. 14, 1953, said would combine “the pageantry of the legitimate theatre with the sheer savagery of intercollegiate hockey.”

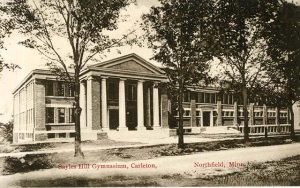

After a tug of war between classes on the ice, competition moved to Bell Field for races on sleds, toboggans, snow shoes and barrel stave skis. A dance at Sayles-Hill Gymnasium (decorated as a circus Big Top) concluded the activities.

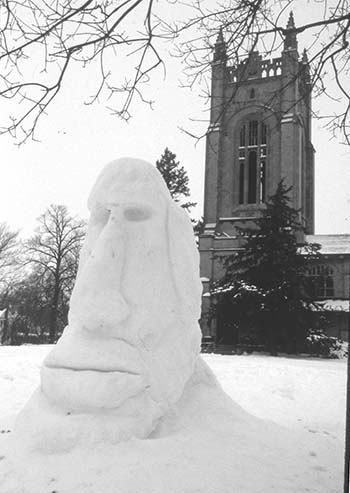

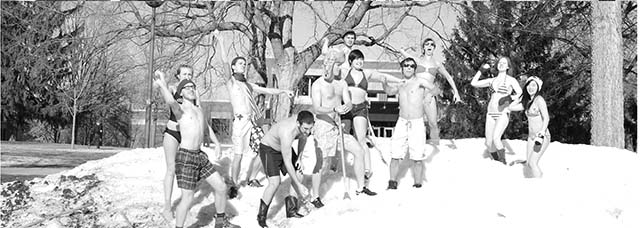

From among the many pictures of snow and ice sculptures that Carleton students have created over the years, I selected a striking snow sculpture of an Easter Island head from 1999. Finally, from the winter swimsuit edition of The Carl of Feb. 10, 2012, here is a picture of Carleton students cavorting in the snow on the Bald Spot at the center of the campus.

Hey, we have three seasons of winter in Minnesota. So go out and enjoy yourselves this January, in any way you choose!