Originally Published in the March 2014 Entertainment Guide

Here in Northfield, insomniacs hear the freight train horns late at night, while during the day many of us are jolted out of our reveries when we hear the familiar sound reverberate through the air. We wait impatiently for the trains to pass when we approach the tracks from the east or west. Hardly anyone glances at the sole remaining boarded-up train station, rather forlornly occupying a position close to the tracks just south of 3rd Street West. Passenger service had ended by 1969 and the era which had begun with the arrival of the first train in Northfield in September of 1865 was over.

During this span of time there were countless arrivals and departures at Northfield depots, including at this last remaining depot which dates back to 1888. Most passenger experiences were cotidian – salesmen plying their trade, students coming to and leaving the two colleges, visitors arriving to enjoy the offerings of this river town while townspeople rode the rails to explore other places. In addition, there were many depot gatherings on special occasions, including sendoffs to soldiers departing to fight for their country in the 1898 Spanish-American War and the two world wars.

I am going to focus on three memorable and historic welcomes at Northfield train depots, involving a presidential candidate and an elephant in 1908, the triumphant return of the St. Olaf Choir from its Eastern tour in 1920 and yet another presidential candidate whose visit in 1952 was the grandest of all.

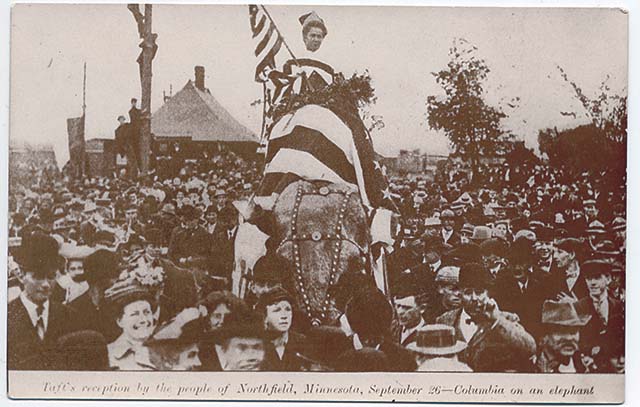

Republican presidential candidate William Howard Taft made a brief campaign stop on Sept. 26, 1908, at the Milwaukee-Rock Island depot in Northfield en route to Minneapolis. It was once common practice for politicians to make short speeches from the rear platform of trains at what were called “whistle-stops” along the rail routes. The Minneapolis Journal reported that “The biggest reception of the day was at Northfield. The Taft club there had borrowed an elephant from a street carnival combination exhibiting in the town and had the party emblem down to meet the Taft train, mounted by a handsome young woman dressed as Columbia, carrying roses and a big flag. Flags also draped her and the big beast, which ambled up to the rear platform and stood there swaying restlessly during all the proceedings.”

The crowd, estimated at between four and eight thousand people, had waited for hours in “nasty cold weather” before the train finally arrived from Faribault about 3:30 p.m. The mayor’s daughter, Mildred Ware, was the “handsome young woman” dressed as Columbia, a poetic female personification of the United States. As soon as Taft caught sight of the elephant, his face broke into a big smile and the press and photographers went wild. According to the Minneapolis Journal, the portly Taft (who weighed at least 300 pounds) said, “I am pleased to see this beautiful emblem of party victory. I should like to mount the animal myself, but I am afraid there isn’t time to rig a derrick to get me on there.”

Jeff Sauve, in his detailed account of this Taft visit in the May 2007 Scriver Scribbler of the Northfield Historical Society, wrote that “Some young men seeking a better view, climbed the nearby telephone poles. One photograph shows four men on one pole, one atop another.” The town had autumnal decorations for its annual Harvest Festival and Street Fair and “Bridge Square was given over to the Patterson Carnival Company with elephant rides, side shows, souvenir sellers, merry-go-round, and shooting gallery.” There was red, white and blue bunting on the 4th Street bridge, with a wire sign of small grain spelling out “Welcome.”

The Northfield News of Oct. 3, 1908, said that Northfield “did itself proud” in its “hearty reception” and that “the next president will have a remembrance of Northfield which will leave a lasting impression with him.” Taft did return as President on Oct. 23, 1911, giving a short talk in pouring rain on the rear platform at the Great Western station en route to Minneapolis. This time no elephants were to be seen.

Former President Theodore (Teddy) Roosevelt also passed by train through Northfield on March 29, 1912. He hoped to succeed Taft to gain a third term after a split in the Republican party. It wasn’t until months later that Roosevelt formed the Bull Moose Party to try to achieve his aim, so no bull moose was on hand to greet him at the depot in Northfield. (Teddy bears were named after him but there is no record of teddy bears being there either.) The stop lasted a mere two minutes, disappointing the thousands who had gathered to greet him. Forty years later this slight would be amended by Dwight David Eisenhower.

But first…

For many years, a train depot was where family and friends would gather to welcome home the St. Olaf Choir after yet another concert tour of glowing reviews. In fact, there is a brief movie of such a welcome after the 1940 tour in the history section of the website northfielddepot.org of the Save the Northfield Depot group. (See accompanying story by Mitchell Rennie on the efforts being made to preserve the 1888 depot.)

But one of the most ecstatic of all the welcomes at the depot involved the 1920 return of the St. Olaf Choir which had impressed the tough music critics in the East. The St. Olaf Choir had grown out of the choir at St. John’s Lutheran Church in Northfield, which was composed of students and other congregation members and led by F. Melius Christiansen, who had been hired as music director at St. Olaf in 1903. The first tour of the newly named “St. Olaf Choir” started out on the Dan Patch railway line in Northfield and made stops in Minnesota, Wisconsin and Illinois in the spring of 1912.

Christiansen had led the St. Olaf Band on a tour of his homeland of Norway in 1906 and then took the St. Olaf Choir there in 1913. Choir tours from 1914 to 1919 were confined to the Midwest where the a cappella St. Olaf Choir was becoming well-known. But, as concert arranger Paul G. Schmidt wrote in My Years at St. Olaf (1967), choir membership was increasing with the end of World War I and, “It was felt that an effort should now be made to bring the choir to the attention of our Lutheran friends and the music-loving public in general in the metropolitan centers of the eastern states” where “no one had ever heard of St. Olaf College or the choir.”

Schmidt traveled to New York City in the summer of 1919 to speak to skeptical potential hosts. Schmidt wrote he would lie awake “trying to think of new approaches” and then by chance he saw newspaper items about a choir coming from Italy to tour the U.S. He thought, “Why should not our people support one of our own American choirs and give it a chance to prove its worth!” This argument worked and the choir of 32 women and 20 men sang its way to the east coast in 1920, leaving Northfield on April 5 for its first concert, held before a packed and approving crowd at Orchestra Hall in Chicago. Subsequent concerts were also enthusiastically received in cities such as Columbus, Pittsburgh, Washington, D.C., Baltimore and Philadelphia.

On April 25, the choir sang at the Academy of Music in Brooklyn and in Paterson, New Jersey, on April 26. Then came the climactic concert at New York City’s fabled Carnegie Hall on April 27 before a sell-out crowd of 3,000.

The critics were unanimous in their praise. The respected dean of critics Henry Krehbiel of the New York Tribune said the choir voices were “exquisitely balanced, fresh and euphonious in quality.” The New York Times praised the “virtuoso” choir and its “body of excellent material, well balanced and trained to a high degree of finish in enunciation, attack and release, phrasing and dynamic shading.” The Evening World rhapsodized about the “benison of song” which the choir bestowed and compared the choir to a “life-restoring breeze from the northwest,” which “sweeps over New York at the close of a suffocating August day.” The New York Globe reviewer said, “There was something singularly inspiring in the sight of these blond children of our Scandinavian northwest” who sang “with the resilient irresistible vitality of youth and the intense conviction of a centuries-old tradition.”

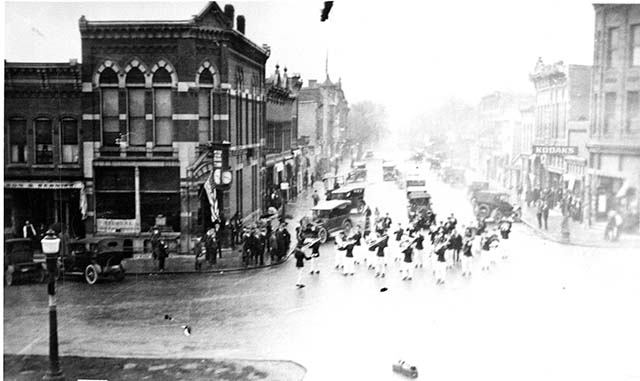

Audiences increased as the choir’s fame spread to tour stops in Rochester, Buffalo, Cleveland, Akron and Toledo. The Northfield News of May 14 proudly summed it all up in a headline with subheads at the end of the tour: “Hearty Welcome for St. Olaf Choir. Return with Laurels Won on Eastern Tour – City and College Greet Them. PUT NORTHFIELD ON THE MAP. Musical America, Thru Leading Critics, Places Local Chorus at the Head of Country’s Best.”

The whole student body, faculty and numerous Northfield residents met the choir at the Milwaukee depot at 9:08 a.m. on May 10. The St. Olaf Band played High on Manitou Heights as choir members disembarked. Cars picked up choir members and the band led a parade through the downtown business section, which had been decorated with flags. The band then led the procession up to the campus. The Northfield Independent of May 13 said that an archway with the words “Ye Songsters, Ho!” greeted the returning singers at the college entrance. At a program at Hoyme Chapel, director Christiansen said, “The choir and band are a natural outgrowth of the culture here. They have grown naturally from a little seed way back in history and like flowers in the woods, grow under favorable conditions. That we were successful was only that the flavor of St. Olaf was given to the world and they seemed to like it.”

M.H. Hanson, New York impresario who helped arrange the tour, called Christiansen “one of the most remarkable music masters of the world.” He also said, “If the city had spent half a million for propaganda, the results would not have equaled what the choir has done without any expenditure whatsoever.” When asked, “Where and what is Northfield?” Hanson said he would tell people of its “flourishing two colleges, working in friendly rivalry, of its splendid farm territory, its well kept stores and streets and its extraordinary natural beauty and attractive college campuses.”

As Dr. Joseph M. Shaw wrote in The St. Olaf Choir: A Narrative (1997), “The 1920 tour was a resounding success in establishing the reputation of the St. Olaf Choir on the national music scene.” The tour introduced audiences to beautiful Lutheran chorales and established the annual choir touring tradition which continues today to give what Christiansen called “the flavor of St. Olaf” to the world. Now, of course, the choir’s reputation is also enhanced by its recordings and international television exposure.

One of the most anticipated arrivals at a Northfield depot took place on Sept. 16, 1952, when Republican presidential candidate and World War II hero Dwight David (Ike) Eisenhower came to make what was called a “major address to the youth of the nation” at Carleton’s Laird Stadium.

Coming from Albert Lea and Owatonna, the 21-car special campaign train carrying Ike and his wife Mamie, advisers and media people made a brief stop at the Rock Island Depot in Faribault. The Faribault Daily News of Sept. 16 reported that Eisenhower was given a “tremendous welcome by some 5,000 persons,” including school children released from classes and a color guard from Shattuck School who presented arms and were saluted by Gen. Eisenhower. After a brief talk on the rear platform, in which Eisenhower encouraged everyone to vote in the November elections, he introduced Mamie who flashed her “famous smile and waved enthusiastically to the crowd.” She accepted a basket of flowers and “seemed very pleased when she and the general were presented with Pak-A-Robes. She stroked her blanket tenderly as she posed for photographers and Ike grinned and made a comment about keeping warm this winter.” (Pak-A-Robes, stadium blankets in zippered cases from the Faribault Woolen Mills Co., were favored gifts for years.)

The train moved on to Northfield where a welcoming committee composed of selected students, Northfield mayor Oakey Jackson, President Larry Gould of Carleton, President Clemens Granskou of St. Olaf and other dignitaries met the party at the Milwaukee train depot. A red Cadillac convertible was waiting to take the Eisenhowers across the 3rd Street Bridge and north down Division Street to Carleton’s Laird Stadium, which was filled to its capacity and beyond. Spilling from bleachers onto the track field, some 10,000 people of all ages excitedly awaited the famous general.

Carleton senior Clifford Stiles had invited Eisenhower through the Carleton Republican Club. (A presidential poll later that fall at Carleton gave Eisenhower 75.9 per cent of the vote over Democrat Adlai Stevenson.) Eisenhower’s address was his only college speech and last in Minnesota before he was elected president on Nov. 4. Students from St. Olaf, Carleton and 14 other colleges came in busloads and car caravans. The Northfield Male Chorus sang and bands played from schools in Cannon Falls, Faribault, Farmington, Hastings and Northfield. Cheerleaders from Carleton and Macalester and three St. Olaf trumpeters led “I Like Ike” cheers. Campaign buttons, banners and hats were sold and St. Olaf and Carleton lettermen manned refreshment booths.

Eisenhower opened his speech with, “My very good friends, and you must be my friends, otherwise I don’t see how both St. Olaf and Carleton could have turned out here together,” garnering a laugh from the crowd. He compared American and Communist ways and said, “If you can by co-operation show that you can outdo, outthink, outwork and outlearn any dictatorship that has ever existed no matter what its force, you will have done your part.” Eisenhower called small colleges “one of the greatest symbols of a free America.” The cheers at the end led Eisenhower to say, “This is the dandiest meeting I’ve had in a long time.”

The Northfield News of Sept. 18 said, “A genuinely warm and human American with his charming wife gave Northfield a day that will long be remembered.”

You may have been there or know someone who remembers this Eisenhower visit. You may have dined in the Depot Bar and Grill in Faribault which is now the renovated Rock Island Depot where Ike’s campaign train pulled in before moving on to Northfield. You can see oral histories of those who have shared their memories of railroad days at northfielddepot.org. Among them: Brynhild (Brynnie) Rowberg speaks of the emotional departures of soldiers, the reactions of farmers to the railroads, the rail riding hobos of the Great Depression, the enjoyment and convenience of riding the Dan Patch line from Northfield past lakes and wild roses, an “absolutely delightful way to get to downtown Minneapolis.” Dick Heibel describes the streamliner passenger trains with internal combustion diesel engines that roared instead of chugged like the freight trains. Bob Will recalls his post-World War II student days at Carleton when students sent their dirty clothing home to mothers via laundry boxes loaded onto trains.

Will, who is a former chair of the Northfield Heritage Preservation Committee, points out that the 1888 depot is a “key building that is representative of a major era in our nation’s history, the railroad age,” when goods and people were primarily transported by rail. And Will warns, “If we don’t save the depot now, we will lose a truly significant part of our heritage and a unique opportunity for our future.”

Further information may be obtained at the northfielddepot.org website.

All Aboard to Save Northfield’s Depot!

By Mitchell Rennie

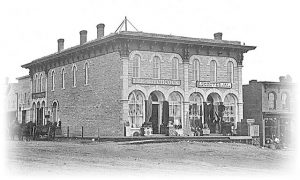

Northfield’s train depot that currently sits just south of 3rd Street West near the tracks is the last existing depot of Northfield’s long railroad history. This depot, known as the 1888 Milwaukee depot, was not the only one to serve the city of Northfield. In fact, over the years as rail lines came and went and different railroad companies purchased and sold rail lines, there were a total of five train depots in town. These depots served both the agricultural needs of the surrounding countryside and the personal transportation needs to cities around the region and the Midwest.

The first depot to be built in Northfield was a small shed south of 3rd St. W. constructed in 1865 by the Milwaukee Railroad. The second Milwaukee depot (1870) and its associated grain elevator were also located south of 3rd St. W. A third depot (1883) came to town along with a new set of tracks that ran from Northfield to Red Wing. This rail line was called the Cannon Valley Line of the Minnesota Central Railroad Company, later the Chicago Great Western. The depot in Northfield that serviced this line was located a block away from the current 1888 station.

Between 1888 and 1889 the construction on the 1888 railway depot was completed where it is today and it became the predominant passenger depot in Northfield. In 1969 passenger trains stopped making stops in Northfield and all train traffic began to be strictly agricultural, and coal/oil carriers, which is all of the traffic found traveling through town today. The depot was retired for good on October 22, 1981.

In 2008, a group of citizens learned that the 1888 depot was scheduled for demolition. The railroad had even offered the depot to the city fire department for firefighting practice. Save the Northfield Depot was formed in 2010 with the aim to salvage and rejuvenate the 1888 depot and move the existing depot to a new location just north along the tracks behind the Quarterback Club Restaurant where it currently lies. Input at public meetings held by the organization indicated that the depot complex should be multi-use, including information for visitors with possible exhibits of the history of the railroads as well as the work of local artists.

The current situation for the Save the Northfield Depot project is one of making plans for the move and fundraising. The project is moving forward with current fundraising at $119,000 raised out of the total $293,000 needed to move and renovate the depot. Rob Martin, co-chair of Save the Northfield Depot, explains that the recent MnDOT decision not to extend the deadline for grant funds to clean the land for the city transit hub will not critically affect the success of the depot portion of the vision. The plans were to co-locate the depot and the transit hub on the same lot; the grant funds were for the transit hub and not the depot portion.

The completed project will be a grand way to finally memorialize the long history of the railroads in Northfield and all the depots which once served the town. The preserved and renewed 1888 depot can then serve visitors and residents of the Northfield community once more.

For more information, go to northfielddepot.org. Donations can be made online or sent to Save the Depot, Treasurer, 712 4th Street E., Northfield, Mn. 55057.