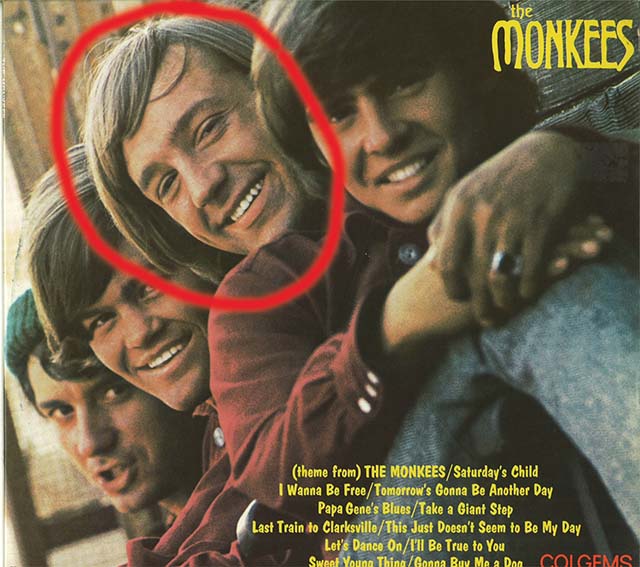

If you filled in the blank with the word “Monkees,” this story will resonate through the soundtrack of your mind for days to come. Or at least until you finish reading this column.

The song starts out, “Hey, hey, we’re the Monkees! /People say we’re monkeying around./ We’re too busy singing/ To put anybody down.” The singing group was designed to be America’s counterpart to the Beatles in the 1960s, frenetic, fun and outspoken. Another Monkees’ line you may recall: “We’re the young generation/And we’ve got something to say.”

Ah, well. Many years have passed now, and the surviving Monkees are part of the older generation. But it appears that they still have something to say. To celebrate their 50th anniversary, the Monkees put out an album this year called Good Times! which, in pure sales of CDs and digital downloads, finished at number eight for the first week on the charts in June, beating out Adele, Prince and Ariana Grande. For one week, the album was number one on amazon.com best sellers.

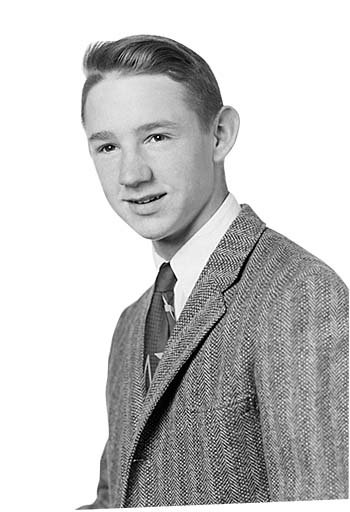

So what’s the connection to local historic happenings? Peter Tork, one of the members of this band, attended Carleton College in Northfield. Peter’s father, H. John Thorkelson (Carleton Class of 1938) had participated in track and was captain of the cross country team his senior year. No doubt this economics professor at the University of Connecticut in Storrs encouraged his son Peter to join Peter’s brother Jeffrey (Class of 1962) at his alma mater. So Peter, who ranked 15 in his high school class of 66 students, left Connecticut for Northfield in the fall of 1959.

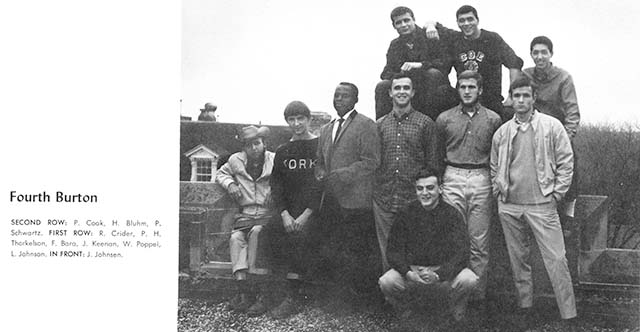

An end-of-year 1963 Algol yearbook photo of fourth floor Burton at Carleton shows Peter wearing a sweatshirt with “Tork” on it, so it seems he adopted this nickname while at college. Alas, Carleton cannot claim him as a graduate, for he flunked out of Carleton twice. He was dropped by the college for low grades in 1960, readmitted in 1961 and then dropped once more after the fall term of 1962, the year he declared an English major.

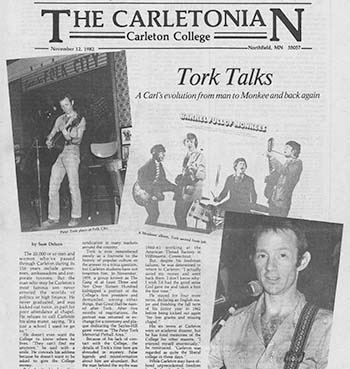

I wrote a June 2008 column about this famous “non-graduate” which was printed in my 2015 book, Historic Happenings at Carleton College. Since then, I have come across some additional information to incorporate, including a rare interview with Tork which appeared in the Carletonian of Nov. 12, 1982, with the title “Tork Talks: A Carl’s Evolution from Man to Monkee and Back Again.” The article was by Sam Delson (Class of 1982) who talked to Tork in the summer of 1982 between shows at Folk City, the legendary Greenwich Village coffeehouse (where Bob Dylan had his first professional gig in 1961). Delson, who is now Deputy Director for External and Legislative Affairs at the California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment in Sacramento, e-mailed me recently that he had been doing a summer internship at The Nation magazine in Manhattan near Folk City. He approached Tork before a show and Tork “graciously agreed to an interview” between sets. Delson told me he remembered Tork “seeming somewhat world weary and displaying a sardonic sense of humor.”

Perhaps still sensitive to his academic failings, Tork called Carleton “just a school I used to go to” and did not want the college to know where he lived for fear of being asked for money. Yet he told Delson that he had some fond memories and kept in touch with a few professors and classmates. He also remembered the college as the place where he acquired social skills.

Tork said that testing out of freshman rhetoric was “one of the great mistakes of my life…I took Shakespeare instead and flunked it.” Tork spent the 1960-61 school year working at the American Thread Factory in Willimantic, Conn. He told Delson, “I actually saved my money and went back there. I don’t know why. I wish I’d had the good sense God gave me and taken a hint the first time.” He stayed on four more terms, through fall term of his junior year in 1962. Tork said he was “kicked out for low grades and missing chapel” (at that time, chapel attendance was required).

Tork told Delson that Carleton was “liberating” for him in that he was introduced to alcohol for the first time (although it was officially forbidden) and he spent much of his time chasing women (even though “they lived on the other side of campus in closed dorms”). Tork said, “I enjoyed myself enormously,” as he recalled having a Friday morning radio show called “Dawn Patrol,” participating in dramatic groups and singing in several folk groups. He performed with Northfield native Peter Basquin (Carleton Class of 1964) who went on to have a career as a respected concert pianist. (Basquin told Delson in a subsequent interview that Tork usually burst into his room at three in the morning to try out new riffs that he’d composed.)

Curious about what Tork had been doing (while avoiding studying), I looked through Carletonian school newspapers to see traces of Tork. Tork, who had played piano since he was nine years old, participated in his first recital at Carleton in December of 1959 when he played Beethoven’s Sonata in F Minor, Opus 2, No. 1. In February of 1960, Peter Tork teamed up with his brother Jeffrey (who played cello in the Carleton Chamber Orchestra) to play seven variations on a theme from Mozart’s Magic Flute. In April of 1960, his piano recital piece was Bach’s Prelude and Fugue in B flat Major. He also took part in student recitals in March and May of 1961.

In November of 1961,Tork began his association with theater, appearing with Peter Basquin in Ulysses in Nighttown. In 1962, the play Mandragola was criticized in the Jan. 24 Carletonian as being “too hammy,” but “the play opened and closed quite charmingly with music written for the occasion by Peter Basquin” and Peter Thorkelson was one of three that played the music. In February, the Players presented Dylan Thomas’ Under Milk Wood, with Tork in the cast and as assistant director. In March, Tork played a Chopin nocturne in recital and in April was a cast member of Apollo of Belloc. He was also in The Plough and the Stars that March and April. In May, Tork played Prelude and Fugue in D Minor by Bach in recital, while also appearing in the cast of The Underground Man.

During Tork’s last term at Carleton in Nov.-Dec. of 1962, he played the roles of Bernardo and the Player King in a production of Hamlet at the Little Nourse Theater. Tork could also be found playing guitar and banjo much of the time at Willis, which was then a student union.

After his second attempt at college failed, Tork wound up in New York City where he lived with his grandmother and entered the music scene by playing banjo in Greenwich Village coffeehouses. There he became acquainted with other musical newcomers, including José Feliciano and Stephen Stills. It was, in fact, Stephen Stills who persuaded Peter to audition for the Monkees in the summer of 1965 in California.

The advertisement in the show biz paper Variety read: “MADNESS!! Auditions. Folk & Roll Musicians-Singers. For acting roles in new TV series. Running parts for 4 insane boys, age 17-21.” The producers liked Stills, one of 437 “insane boys” who tried out for a part, but supposedly his hair was too thin and his teeth were crooked. Stills said he had a friend who resembled him, but with better hair and teeth. Tork decided to give it a try, despite being 23. (Tork told Delson, “My teeth should be better, because I paid enough for them.”) Tork won the part and Stills had to content himself with going on to play in Buffalo Springfield and Crosby, Stills and Nash (and sometimes Young).

Thus it was that musicians Mike Nesmith and Peter Tork, with actors Micky Dolenz and Davy Jones, came together as the Monkees. Their first single, Last Train to Clarksville, was released on Aug. 16, 1966, just weeks before the television show had its premiere on Sept. 12. The song shot up the charts to number one by Nov. 5. Their second single, I’m a Believer, hit number one in eight countries. Six of their singles made it into the top 10 and four of the six albums recorded before Tork left made it to number one. The magazine Rolling Stone reported in a May 11, 2012, story called “Top 25 Teen Idol Breakout Moments” that “In 1967 the Monkees sold more records than the Beatles and the Rolling Stones combined.” (By the way, Tork played Paul McCartney’s five-string banjo on George Harrison’s 1968 debut solo album, Wonderwall Music.)

The television show lasted two seasons and won the group an Emmy Award for outstanding comedy series for 1966-67. Among the hits from their albums were (I’m Not Your) Steppin’ Stone, When Love Comes Knocking (written by Neil Sedaka), I’m a Believer (written by Neil Diamond), Pleasant Valley Sunday (written by Carole King and Gerry Goffin), Daydream Believer, Shades of Gray, and, of course, Hey, Hey, We’re the Monkees. Tork told People Magazine in 1985: “The 60’s were a very schizoid period. We had, on the one hand, a lot of hope and good cheer and gentility going on, and on the other, a lot of pretty brutal stuff. I think in some ways the Monkees were the distillate of the cheery side. They were the epitome: ultrasharp, ultragood cheer, ultraharmless.”

Early on, instrumentation was provided by studio musicians, including Glen Campbell and Leon Russell. But all of the Monkees could play and did, starting with their third album. Tork had studied classical piano and could play five-string banjo, drums, guitar and bass, among other instruments. The unfair perception that they were somehow a “fake” band may be why they are not in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland.

During his 1982 interview with Tork, Sam Delson asked him about the 1967 tour of the Monkees which gave guitarist Jimi Hendrix his first concert tour exposure as the opening act. Delson told me, “I’d heard that the Monkees’ young fans booed Hendrix off the stage. He confirmed that it had happened, and said it was unfortunate that Hendrix had been placed in that position, but understandable that the Monkees’ young fans might not have appreciated Hendrix’s greatness.” Hendrix left the tour early.

The last Monkees television show was March 25, 1968. Actor/screenwriter Jack Nicholson and director Robert Rafelson put out an unsuccessful psychedelic movie starring the Monkees called Head in October of 1968 (which has gained a cult following). After a Far East tour, Tork bought out his last four years with the Monkees in December of 1968 and was the first to leave the group. Tork told Delson, “I wanted my own musical identity separate from those guys. But, unfortunately, that never came to pass.” Delson told me that when he asked Tork if his first solo project had gone far, Tork replied, “Sepulveda,“ meaning only as far as Sepulveda Boulevard on the west side of Los Angeles.

Tork went on to play in several musical groups, performing in folk festivals and small clubs. He also tried teaching in California, went through three marriages and faced up to substance abuse problems in the 1980s. In March of 2009, he battled a rare cancer of the head and neck and underwent radiation treatments.

Delson wrote in his 1982 story that Tork’s Folk City shows revealed him to be a “talented and versatile musician,” who “displayed his skills on the piano, banjo and guitar with equal aplomb. His stage presence was warm and charismatic, and his song selection was eclectic.” Tork played original compositions, one obligatory Monkees song and other pieces ranging from bluegrass standards to Bach piano sonatas and from Chuck Berry to the Grateful Dead. Tork’s “thin, reedy tenor” had limited range, “but the spirit was there.” Tork gave Delson his “stock answer” about a Monkees reunion: “If I thought there was any chance of there being anything new in it as well as a decent piece of change, I would go for it. But without both artistic/authentic and pecuniary considerations, forget it.”

In 1986, a Monkees TV show rerun marathon was broadcast on MTV, followed by reruns on Nickelodeon, sparking renewed interest in the group. A 20th anniversary tour by Dolenz, Jones and Tork followed, with Nesmith joining occasionally. Nesmith did not need the money, as he inherited $25 million when his mother, Bette Nesmith Smith, died in 1980. She had made a fortune by inventing Liquid Paper.

In the 1990s, Tork discovered an affinity for the blues and started a touring band called Shoe Suede Blues. But, of course, the big bucks came with the Monkees and all four Monkees participated in an 11th album, Justus, in 1996, their first recording all together since 1968. There were sporadic reunion shows after that, with sometimes acrimonious results, until the unexpected death by heart attack of Davy Jones on Feb. 29, 2012. Nesmith, Dolenz and Tork went on a cross-country U.S. tour in November and December of that year, using recordings and video in tribute to Jones. Subsequent tours followed.

In this, their 50th anniversary year, the Monkees were back in the news with their 12th album, Good Times! Two sample headlines: Rolling Stone, May 24, 2016, “How the Monkees Got their 1960s Groove Back,” The New York Times, May 25, “Hey, Hey, the Monkees are Busy Singing Again.” The Times critic Jon Pareles described Tork’s song Little Girl as a “wandering, eccentric waltz that would have been home in the late 1960s” and concluded, “Fifty years later, the Monkees are still endearing.” Rolling Stone’s Rob Sheffield said, “Monkees freaks have waited far too long for this album. But it was worth the wait.”

Good Times! is a Rhino studio album with contributions from songwriters known to be Monkees fans (Ben Gibbard of Death Cab for Cutie, Andy Partridge of XTC, Rivers Cuomo of Weezer, Paul Weller of the Jam and Noel Gallagher of Oasis) with Fountains of Wayne front man Adam Schlesinger as producer, as well as tunes from the ’60s vault. It includes an unreleased 1967 recording of Davy Jones singing a Neil Diamond song, Love to Love, a new vocal by Tork to the Carole King-Gerry Goffin tune Wasn’t Born to Follow and the title song, Good Times!, which had been written by Harry Nilsson for his friend Dolenz in 1968. The album was recorded in February and March, largely at Lucy’s Meat Market studio in Los Angeles with other musicians in addition to the three Monkees. However, Dolenz said, “There was no reason for us to be all there at the same time. The days of all standing around the mono microphone singing harmonies are long gone.”

Dolenz and Tork embarked on a 50th anniversary tour, starting on May 18 in Ft. Myers, Florida, with Nesmith joining them at a sold-out Pantages Theater show in Los Angeles on Sept. 16. Minnesotans with Monkee mania have been passed up, as remaining tour dates in November are in Waukegan, Illlinois, Saint Charles, Missouri, Lincoln, Rhode Island and Englewood, New Jersey, and then Dolenz and Tork will embark in December on an Australian tour.

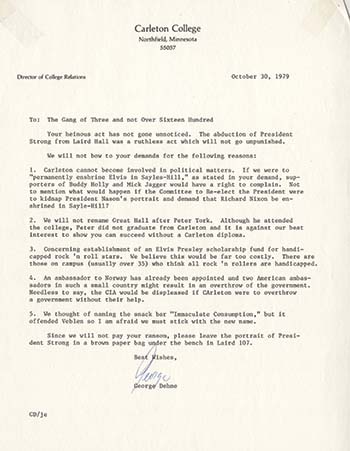

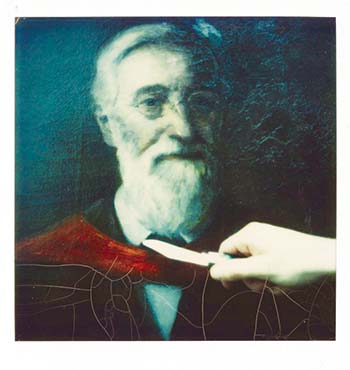

So, the question arises, has Peter Tork’s time in Northfield been forgotten? It hadn’t been in 1980. That year, Peter Tork was memorialized at Carleton at the dedication of the Tork Pinball Area after the Sayles-Hill Gymnasium was remodeled into the Campus Center. In October, 1979, a portrait of Carleton’s first president, James W. Strong, was stolen from Laird Hall near the president’s office and replaced overnight by a day-glo velvet portrait of Elvis Presley. A ransom note from a group calling itself “The Gang of at Least Three and Not Over Sixteen Hundred” had several demands, including renaming Great Hall after Peter Tork. In his response, the Director of College Relations, George Dehne, refused to rename Great Hall because Peter Tork did not graduate from Carleton and “it is against our best interest to show you can succeed without a Carleton diploma.” The gang’s threats escalated, as the kidnappers sent a snapshot of the Strong portrait with a knife held at Strong’s throat, followed by a photo of Strong’s ear (“an anatomical sample of the President”).

Finally, the Gang of at Least Three and Not Over Sixteen Hundred asked only that the Sayles-Hill pinball room be named after Peter Tork. Dehne replied, “The college refuses to negotiate with kidnappers. But, it just so happens that we were planning to name the pinball area after Peter Tork, anyway…Remember that we are doing this because it is an appropriate gesture to a fine non-graduate, not because we have been coerced by your illegal act.” On March 5, 1980, the Tork Pinball Area was formally dedicated at Sayles-Hill with a sign and a champagne reception. (The sign has since disappeared.)

In an interview in the Baltimore Sun of May 26, 2016, Peter Tork commented on the question of whether the Monkees belonged in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. He said that, although he would vote for inclusion, “if there was a hall of fame for television casts who became pop groups in their own right, we would be the only candidate. There’s a great deal to feel good about.”

Local fans can also feel good that Peter Tork spent some time “monkeying around” Northfield.