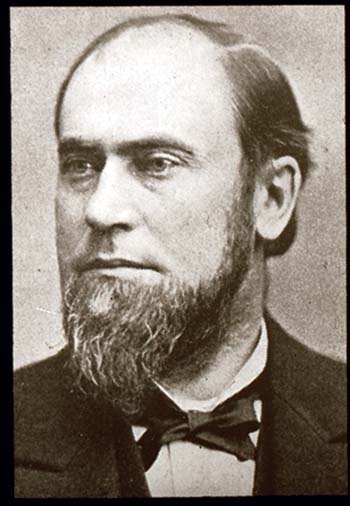

I never thought I would fall in love with a man named Hiram when I moved to Northfield in 2004. But I did. Just my luck, he lived in the 19th century in this town. When you come downtown, you see his name on the Scriver Building at 408 S. Division St., now the home of the Northfield Historical Society and site of the famous 1876 James-Younger bank raid.

I could fill up a whole column just on Hiram Scriver’s accomplishments, but I am going to let you meet the man through his own words, as much as possible. I think you will see why I have become enamored of him.

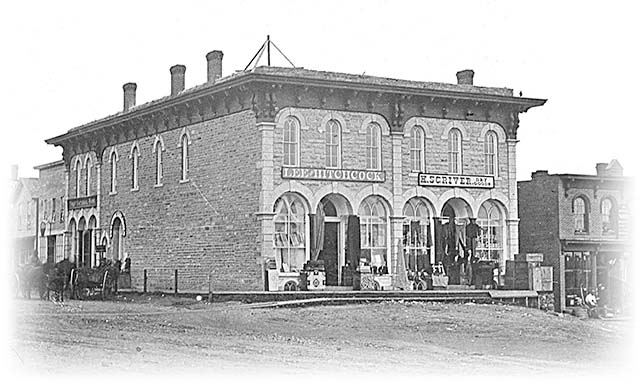

Born in the province of Hemmingford in Quebec in 1830, Scriver spent some time in Potsdam, New York, and arrived in the embryonic town of Northfield in June of 1856 at the age of 26. That month he bought a small wooden building which had been used since March as Northfield’s first store. Northfield’s founder, John W. North, convinced Scriver to move this store south to provide space for a town square. The current distinctive limestone building was built in 1868 to replace Scriver’s frame store. After Northfield College (later renamed Carleton College after a benefactor) was established in 1866, Scriver donated this old building to the college in 1869 to be used as a residence hall. Scriver had a personal interest, in that he was a founding and lifelong trustee of the college. His donation was moved to the west side of Washington Street across from the first building used by the college, the American House, which had been built by John North as a hotel. Scriver’s wooden structure was given the odd name “Pancake Hall” due to the students’ predilection for making sourdough pancakes. The new stone Scriver Building in what was then called Mill Square was occupied by Scriver Dry Goods and Lee & Hitchcock General Store. The First National Bank opened there in 1873 and awaited its historic date with outlaws three years later.

In 1875, Hiram Scriver was elected the first mayor of Northfield under the city charter and, in that capacity, he gave a speech to the Old Settlers’ Association on Jan. 27, 1876, which vividly brings Scriver and early Northfield back to life to us today. Scriver described the scene he saw traveling in a stage from Hastings in June of 1856: “As the prairies spread out before us in their living green, dotted with wild rose and other flowers, was it any wonder that the heart of the traveler from the barren hills of the East or the wilds of Canada should leap for joy within him, and that he should feel that this is indeed a goodly land?”

As the stage drove into Northfield, Scriver beheld the “noble forest” with a “magnificent grove of elms near the mill” and, he told the old settlers, “need you be surprised that I ordered my trunk taken off, and felt at last I had reached my journey’s end…” The old mill sawed up the logs to build the houses of the new town and in the shadow of the grist mill, Scriver and a friend “threw out black bass with a spear as fast as we could handle them.”

Scriver recalled his first one-story, 20-by-30-foot building, set on blocks, whose stock in trade “amounted to the modest sum of $500.” He described himself as “a pale-faced youth who had seen too much indoor work for his health,” invigorated by the breezes that blew between the planks and loose floorboards of this store when he stayed there overnight. Brine would drip through the floor from pork or fish barrels, leading an occasional “venturesome calf,” hungry for salt, to crawl underneath “and then there was no more sleep from the rattling and banging of the floor boards till that calf was dislodged.” For this reason, Scriver said, his new Scriver Building of 1868 “has been sunk to the solid rock.”

Scriver also spoke of the debating club first organized at the schoolhouse on Oct. 1, 1856. (Fortunately, minutes of this Lyceum Society have been preserved. Scriver was the first treasurer, while town founder, John W. North, was the first president.) One of the first debate topics was “female suffrage,” and Scriver said, “Thus early did this great question agitate the minds and hearts of the community. It was difficult to find anybody to take the negative, for the male sex especially felt that the great necessity of the house was for the immigration of the fairer sex. Young men and old bachelors, therefore, were spoiling to have women vote, and every inducement was offered to get them here.” (The Oct. 22, 1856, minutes indicated that the society, “with the assistance of the ladies, decided in the affirmative,” after which everyone sang, “There’s a Good Time Coming.”)

The debating society was outgrowing the schoolhouse and John North offered property for a Lyceum building in April of 1857. (This building at 109 East Fourth St. is now Northfield’s oldest structure.) The first meeting at the new site took place on Nov. 4, 1857. Scriver said in his 1876 speech, “The long winter evenings were spent in debate, music, readings, original papers, etc. Of course, we had some astonishing bursts of eloquence, for genius felt in this free air untrammeled.” The Lyceum was also used as a library, reading room, site of occasional church and town meetings and a practice room for a choir.

Scriver told the old settlers, “As we felt the necessity of the civilizing influence of music in our semi-savage state, a band of young men was formed, led by John Mullin. Time hung heavy; money and girls, two prime necessities of life, were scarce.” Consequently, the principle was that even a counterfeit bill should not be refused, because “it helps to make trade lively. Keep it circulating.” As for the lack of females, Scriver said, “If a sleigh ride was gotten up, a sort of lottery was resorted to, and sorry was the poor wight [person] who was not paired off.”

Scriver also talked of “those severe winters which gave our state such a bad reputation” in the East: “Mr. Jenkins had a boarder who froze his toes while asleep in bed with his feet near a window.” Scriver described the boarders at the two hotels in town as a “turbulent, roistering, good-natured and withal complaining, whining crew” whose “sluggish blood” was stirred by “scant fare and tough beef.” These boarders enjoyed teaming up on any “poor traveler who happened along.” At the dinner table, one man would distract the traveler, while another would be swiping “his pie or cake, or any little delicacy.” Overcoat pockets would be rummaged through “and bottles were sure to be confiscated for the public good.”

Scriver then recounted an incident in the spring of 1857, when the river was at flood stage and “a young man ventured to go over the dam,” swamping his boat and nearly drowning. When the man was hauled up onto the bridge, his landlord walked up to the “almost lifeless body” and kicked him, saying, “I’ll teach you to go and drown yourself until you have paid me your board.”

Scriver’s facility with words (and general amiability) served him in good stead during the years when the Lyceum Society was flourishing. Positions were rotated within this society every month and Scriver filled every one of them, but he was at his best as secretary. When the Jan. 14, 1857, debate topic was “Resolved: That dancing is a proper amusement for young persons,” Scriver recorded that the resolution was carried in the affirmative, 20-3, “after its discussion socially and politically, from Adam to our progenitors.” At the next meeting, Jan. 21, he wrote, “Singing was called for, but being like our thermometers subject to great variations. We are now suffering under the minimum of the fever, consequently the music was minus.” The debate topic that night was “Resolved: that territorial extension is the true policy of our government,” and Scriver noted that “Buckham advanced and rebutted his own arguments with equal favor and effect.” At the next meeting, Scriver wrote that when someone suggested that the president of the Society should furnish a song in the absence of the choir, the president was “excused upon the plea that his feelings would not admit of his inflicting unnecessary pain upon his fellow creatures.”

In early February of 1858, the ladies of the Lyceum inaugurated a newspaper called the “Portfolio,” written by members and read by the female editors at the meetings. The Northfield Public Library has a few of these submissions saved in a scrapbook on “Old Northfield” put together years ago by Mrs. Charles A. Bierman. One of these articles is labeled “Northfield Lyceum Paper 1858, H. Scriver, Contributor.” In his offering, Scriver wrote a notice, “To all whom it may concern.” He said: “At a meeting of bachelors convened for the purpose of looking after their own interests (as no one will do it for them),” it was resolved “that our purses are reduced from a beautiful curve to a geometrical straight line,” due to “enormous expenditure for board and washing.” Scriver said that a joke is a joke, but “charging 17 cents for washing a pair of socks is no joke” and “If no move is made towards relieving our afflictions, we will be driven to the desperate remedy of marrying – and may mercy be extended to our souls.”

Scriver did get married to Clara E. Olin in 1860, and I would like to tell you that he lived happily ever after. But he endured several blows in his personal life. Their only child, a son, died in 1863 at the age of two and his wife perished following a run-away horse accident in which she was thrown from a buggy in 1884. Scriver married again in 1886 to Delia M. Vanderbilt. His obituary in the Northfield News after his death on June 1, 1890, said that her devotion to him “during the last years of his life did much toward alleviating his sufferings.” He had been in ill health for his last 20 years “but always lived in hope that his condition would improve and bore his sufferings with patience and Christian fortitude.” He did not retire from business until the month before he died.

Tributes to Scriver poured in, lauding his contributions to the town, including service in the legislature, on the school board, with his Congregational Church and Carleton College and as a director of First National Bank. The “History of Rice and Steele Counties” in 1910 said that Scriver’s “life and character were largely influential in determining the high standard maintained in Northfield from the beginning to the present time.”

After Delia Scriver’s death in 1927, the Scriver Building was owned by heirs of Hiram’s brother, Albert, until it was sold in 1929. Delia Scriver had left a memorial fund in her husband’s honor for the Northfield Public Library which is still used today. That is very fitting, since a bequest from Hiram Scriver had instigated a tax-supported library in 1898 in the YMCA building at 304 Division St. (now the Northfield Arts Guild).

This year, as the Northfield Public Library marks its 100th year in the subsequent library building financed by Andrew Carnegie, Hiram Scriver will be recalled as the “father of the library.” And Scriver’s memory is perpetuated by the building cared for by the Northfield Historical Society which still bears his name in the heart of Northfield.

I do wish I could have known Hiram!

Thanks to the Northfield Historical Society and the Northfield Public Library for material used in this story. And to the inimitable Maggie Lee for retrieval of Hiram Scriver’s 1890 obituary.