Originally Published in the May 2014 Entertainment Guide

“Do you remember your first bike?” This is the question KYMN radio’s Wayne Eddy likes to ask people he is interviewing on his Mon.-Fri. morning show. This year marks Eddy’s 50th year in broadcasting (all but the first four in Northfield) and this Minnesota Broadcasting Hall of Famer knows what questions will evoke immediate responses. Bicycle riding seems to be one of those universal experiences which we can readily share with others, even if the first bike simply marks a passage between our riding tricycles and driving motorized vehicles.

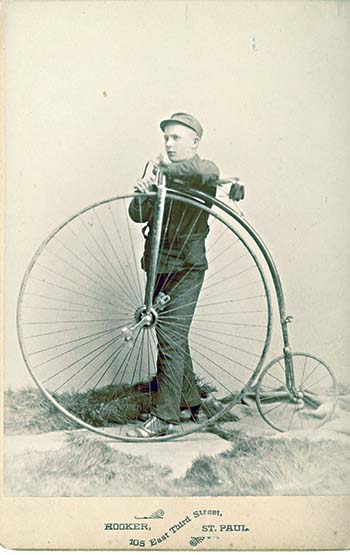

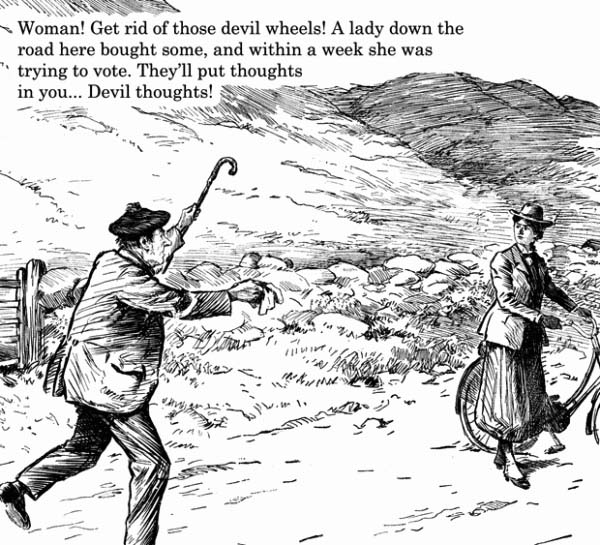

The high wheel bicycle was first built in the U.S. in 1878 and was especially popular with daredevil young men not afraid to take “headers” onto the ground, such as this young man in 1887. Courtesy of Carleton College Archives

I don’t remember my first bicycle, but I do remember my favorite. It was a sleek black three-speed English bicycle with narrow tires, hand brakes and double baskets on the back to carry my tennis racket (in its wooden press) to the South Dakota State courts which “townies” used in the late ’50s and early ’60s for summer recreation. I have many joyful memories of hopping on my bike to visit friends, get to the Brookings swimming pool, fish for crawdads in the creek or ride to the Dairy Queen at the outskirts of town for an ice cream cone.

I even had a name for my bike: Black Shadow. Back in 1895, a woman named Frances Willard, who was president of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, had a name for her bicycle, too. She took up bicycling late in her life at the height of the 1890s bicycling craze and called her bike “Gladys,” for its “gladdening effect” on her health. In her book A Wheel Within a Wheel: How I Learned to Ride the Bicycle, this well-known proponent of temperance and women’s suffrage said that since the age of 16 she had been “enwrapped in the long skirts that impeded every footstep” in walking and, heeding a doctor’s advice to “take congenial exercise,” she got a bicycle. It took her three months of practice but at last, she wrote, “I had made myself master of the most remarkable, ingenious, and inspiring motor ever yet devised upon this planet.” She was not alone in her euphoria. In 1892, Wild West sharpshooter Annie Oakley professed to love her bike as much as her horse.

While researching other topics, I kept running across ads for many models of men’s and women’s bicycles in newspapers in the last part of the 19th century. With winter’s grip finally released around here, I thought a bicycle-themed story would be a breath of fresh (spring) air for May.

The first reference to a bicycle I could find was in the Carletonia of May 1, 1882: “Carleton has a bicycle club of one member. For further information inquire of O. Lockwood.” A modest start. The next year, both Northfield and Faribault had town bicycle clubs and 13 years later the Northfield News of April 4, 1896, wrote, “It is needless for parties living in Northfield to go out of the city to purchase wheels, as nearly every manufacturer has an agent here and prices are by far lower than in the cities.” A list followed of the store locations and names of local riders who endorsed certain models. In 1897, as booming sales produced bicycle prices below $100, more than two million bicycles were sold in the United States, or about one for every 30 persons. By 1898, you could buy a basic model for $30.

How had this happened? One word: Safety. That was the name given to the design change, which led to the bicycle craze at the end of the century. In 1885, the Rover model came out with two wheels the same size, a rear chain drive and direct steering.

Before that, bicyclists rode ordinary bikes. That is to say, bicycles with the large wheel in front and smaller one in the back called “ordinaries,” “high wheels” or “penny farthings,” which been developed in England. These bicycles were shown off at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial exposition, the one where Northfield flour won a medal while the James-Younger Gang was attempting to rob the First National Bank. These high wheelers had replaced the French pedal-driven velocipedes, nicknamed “boneshakers” due to the uncomfortable ride from their stiff construction and iron wheels.

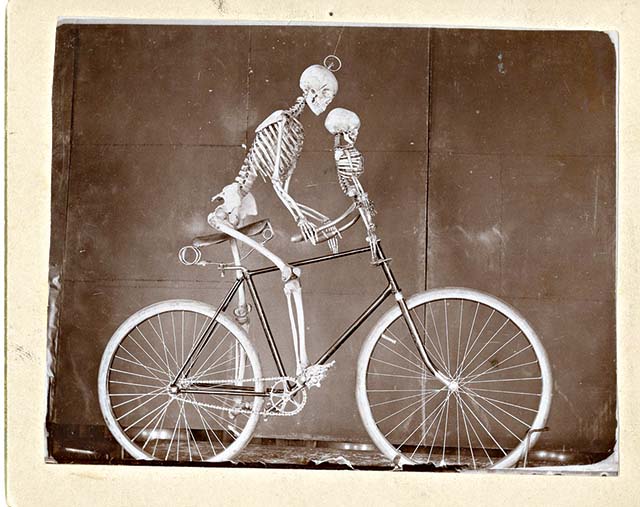

The bigger the wheel, the faster one could go and, in 1878, the first ordinaries were built in the United States and became popular with daredevil young men, in particular. There was an “unsafety” factor to this design, since the rider was so high up that there were dangers of toppling over the front wheel (“taking a header”) when encountering road hazards. There was little braking ability and “breakneck speed” could indeed break a neck. Yet, these bicycles began to catch on and the League of American Wheelmen was formed in 1880 to promote cycling interests, including better roads.

A humorous acknowledgment of the risks of bicycling came in the first Northfield Bicycle Club announcement in the Feb. 22, 1883, Rice County Journal. After listing the officers of the 12-member club (including a bugler), the report noted that “one necessary officer” had not been named “whose services will probably be needed more than that of any other, we mean a surgeon…We would advise the physicians of the city to apply for honorary memberships.”

This club used the Central House hall for practice and ordered new bicycles and uniforms. By April, 16 members were meeting in rooms of the McClaughry block, waiting for the mud to subside so they could ride outdoors. In June, two members “took a run to Cannon Falls on their wheels and claim to be the first exhibitors of the machine in that lively city.” The trip was made in one hour and 40 minutes and was followed by a ride to Dundas that evening. By the end of that month, the members were making extended tours through Rice County.

Meanwhile, minutes of the Faribault Bicycle Club show it was formed in March of 1883, led by William Blodgett (who worked in his family’s lumber business in Faribault). The club resolved that no sidewalks would be used, “except in cases of urgent business and then only when the streets will not permit of their passage.” They also adopted a uniform including shoes, accepted an invitation to visit the Rochester Wheelmen and agreed to levy a 50 cent fine for those missing meetings. Their meeting place was a “stone building opposite the Brunswick” (possibly at 120 Central Ave., the Batchelder’s Block, built in 1868-1869).

Bicycle racing had begun with the advent of the high wheel and was featured in Northfield’s Independence Day festivities of 1883. The July 5 Rice County Journal described a grand procession from the city hall to city park, including 31 men on bicycles and the fire department apparatus “tastefully decorated with wreathes, flowers and bunting.” Afterwards, 2500 celebrants gathered at the county fairgrounds (then located in Northfield) to see a bicycle tournament of several heats with two bicyclists from Faribault, 13 from Minneapolis, three from St. Paul and 13 from Northfield. Those from Northfield “made a grand and interesting display,” with only a couple “headers.” That August, several Northfield club members rode on sandy roads to St. Paul, 57 miles in seven hours, claiming it to be the “longest run on record in Minnesota.”

At the end of August, the Northfield club sent 21 members (said to be the largest number from outside of the Twin Cities) to cycling competition at the Minnesota State Fair, with $100 prizes at stake for one and two-mile dashes. Shortly thereafter in September, Minneapolis hosted an international “championship of the world” and the Rice County Journal of Sept. 6 reported that Northfield and Faribault “bore off a goodly share of the honors from the late bicycle meet in Minneapolis.” Hart Johnson, “a Northfield boy,” was awarded a gold watch and chain for winning the two mile race for the “championship of Minnesota, thus giving Northfield the glory of being the home of a hero of the sporting world.” Johnson “made better time for a mile than the champion of the world had done in Minneapolis in his three-mile race.” Northfield’s captain Nye G. Young was elected treasurer of the newly formed state league of wheelmen and William Blodgett of Faribault was elected vice president, “making Faribault proud.”

As 1883 drew to a close, the Faribault Bicycle Club seemed to be more interested in dancing than bicycling (which perhaps makes sense in the winter). A Committee on Dance arranged for printed programs and invitations at a cost of $20 and rented the hall for $25. A Faribault band beat out a Winona band to furnish music for the $2-per-ticket event which was held on Jan. 30, 1884. The club then agreed to rent the back of the bicycling club room for use as a dancing hall for one year and the second “club ball” was held on April 16.

For unknown reasons, the members tendered their resignations at the April 26 meeting and the club was reorganized with new member names on July 7. The minutes which survive end with a quorum not being present on July 26, the second meeting of the new club.

There was at least one “issue” with bicyclists: The Rice County Journal of Sept. 27, 1883, “commended” an article from the Wheelman magazine about use of the bicycle on Sundays, the traditional day of rest. As long as the bicycle was “a means of exercise and enjoyment,” it should not be used on the Sabbath, “even for church-going.” The article shot down the idea that one might spend Sundays studying God through nature on a bicycle, saying, “Greater than nature’s book and nature’s law is the Book of books and its law: ‘Remember the Sabbath day and keep it holy.’ Here, knights of the wheel, is an opportunity for self-sacrifice and the cause of principle.”

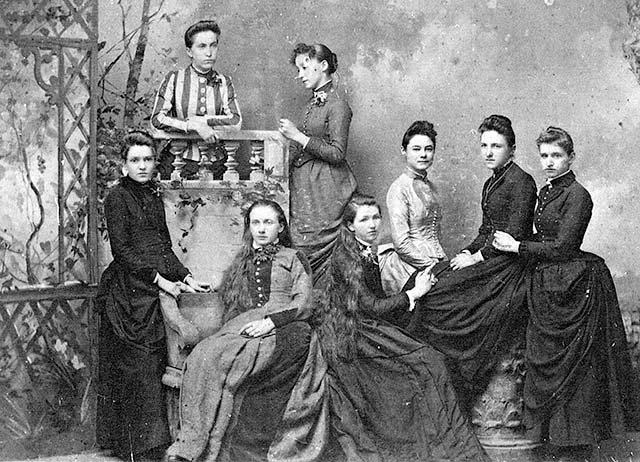

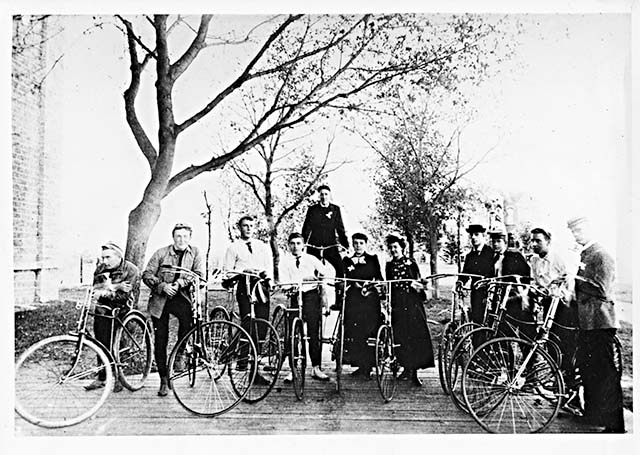

The advent of the “safety” bicycle in 1885 brought wheels to knights and ladies alike. Pneumatic tires patented in 1888 added to riding comfort. Ten years after Carleton had a one-man bicycle club, the Algol yearbook for 1891-1892 named 15 club members, including two females. W.W. Dean is listed as “Lieutenant” and, fortunately, the Carleton College Archives has a memoir of William Warren Dean written in 1938 in which he recounted his bicycling experiences. Dean moved to Northfield as a child and attended Carleton Academy and Carleton College, graduating in 1896.

Dean wrote, “We had long had what was known as high bicycles. I had several myself. We thot they were the last word until the new safety came in…We felt like a bird soaring in the wind. Roads and streets were soon full of your hellions known as ‘scorchers’ who rode all hunched up like an inverted letter ‘U.’ Then came models with a dropped frame for the ladies.” Dean said the bicycle was a boon for ladies because about the only exercise a college girl had was crocheting or playing the piano.

The prospect of women on bicycles was not universally welcomed, however. Dean said the “spinsters” were “highly alarmed, horrified and shocked…When anything involved the morals of our sisters and daughters, they believed in lashing out. The head lady at the college Miss X. denounced the new bikes as being shockingly indecent and immoral and announced that no C.C. [Carleton College] girl would be allowed to ride one or only over her dead body.”

When Carleton’s Bicycle Club was organized, there were two girls attending college who had bikes. Dean wrote, “I can remember how we begged and pled with those two girls to join the club and come out and have their pictures taken with the young men. They were two shy mouse like, hesitant little girls, about 17.” When the two agreed to be photographed, Dean said, “We were terribly scared about it, and ashamed too, because we fully expected both of them would be expelled for their brazenness and shamelessness.” Dean praised their “real courage” and said, “There had to be pioneers and they were the first. Soon almost as many girls rode as men.”

Then, Dean wrote, “The great anti-bike furor had barely died down when it flared up worse than ever.” What happened? “Some girls had dared to ride down the streets attired in the new ‘bloomers.’”

Bloomers were not actually new. The loose trousers gathered at the ankle worn under shortened skirts were named after Amelia Bloomer, who promoted (but did not originate) this style in the 1850s in her newspaper The Lily in Seneca Falls, N.Y. (the site of a woman’s rights convention in 1848). A push for less restrictive clothing was accelerated when women wished to take advantage of this new bicycling activity. Just picture Scarlett O’Hara being cinched into her corset in Gone With the Wind and imagine someone trying to ride a bicycle thus attired. Fashion dictated layers of petticoats under long skirts and dresses. No wonder the “rational dress” movement of England in 1881 called for underwear weighing no more than seven pounds.

Dean wrote that seeing girls riding bicycles in bloomers was “the last straw for Miss X. Such girls were denounced as hussies and worse. In spite of all she could do, and she ruled her girls with an iron hand so they scarcely had a right or privilege in the world, bikes and bloomers came in.” (The Northfield News of June 8, 1895, commented that the “bloomer bicycle costume” which “gives free play to the limbs and minimizes the danger from accidents is no longer a pronounced novelty, but is often seen on thoroughfares much frequented by fair cyclists. In fact, bloomers are so common that many variations of the original style are observed.”)

Dean called it “the beginning of the bicycle era, one of the greatest manias the cockeyed old U.S. has ever had. People were getting bicycle crazy.” Dean certainly was. He decided to “show off” and ride to the Chicago World’s Fair during the summer of 1893 on his “heavy and clumsy” bicycle that “would have been a joke today.” He wrote, “Every day was heart-breaking brutal exertion. It took every iota of physical and mental power, but I fancied I was a great hero…” It took Dean 6 ½ days to travel 500 miles. But he made it and described the fair as the “greatest manmade spectacle the world has every known.” (Although there were bicycles on display, the main attraction was a different kind of wheel: the world’s first Ferris Wheel, seen by the 28 million visitors over six months.)

Dean also wrote of other bicycle adventures, including meeting horses on the road that “would invariably begin to prance stand on their hind legs, panic stricken.” He learned to get off his bike, “lay my bicycle down in the weeds and wait till they passed… It was exasperating.” One time in Decorah, Iowa, Dean encountered a team of mules, which “bolted the instant they saw me.” They were carrying tanks of “splendid rich pure cream,” which fell and “smeared the whole landscape.” Dean panicked and “rode until I was near dead from fatigue” to get away.

The bicycle mania involved “individuals, small groups and large parties” who “took long trips, ranged over the countryside and ‘desecrated’ the Sabbath,” wrote Edgar Bruce Wesley in a 1938 book about Owatonna. A “young wheelmen” club was formed in town for the promotion of fellowship in 1894. The ride from Owatonna to Faribault, with a steep climb just beyond Medford, was said to be the test of cycling ability.

In February of 1895, Bush’s Bicycle Rink opened inside a large hall in Northfield’s Central block. The rink had a run of 20 laps to the mile for only $1 for the season. In August, an announcement of a new bicycling club gave an estimate that Northfield had more than 100 gentlemen and a dozen lady riders. At the Minnesota State Fair, an entire day was devoted to a “bicycle program,” including a mammoth parade with a bicycle band from St. Cloud, trick bicycle riding and racing.

In 1896, leading women’s rights advocate Susan B. Anthony said she thought bicycling “has done more to emancipate women than anything in the world. I stand and rejoice every time I see a woman ride by on a wheel…Off she goes, the picture of free, untrammeled womanhood.” Sans chaperone.

In 1895, Anthony had asked a reporter, “Why, pray tell me, hasn’t a woman as much right to dress to suit herself as a man?” There were those who fearfully watched long-established gender rules of behavior and dress being broken down as women gained more independence and freedom. (The expression “Who wears the pants in the family?” is a vestige of this attitude.) The backlash against this “new woman” who was asking for equality was illustrated in 1897 when it was proposed that women should be admitted as full members of Cambridge University in England. Male students strung up an effigy in the main town square. It was a woman on a bicycle. Bicycling historian Sheila Hanlon wrote that when the resolution failed, “the triumphant mob tore down the effigy” and then “savagely attacked the mannequin, decapitating and tearing it to pieces in a frenzy.” Full degrees were not granted until 1921.

The bicycle craze waned as the automobile craze took over after 1900, profiting from the paved roads promoted by the bicyclists. One might say bicycles also “paved the way” for other transportation. The first U.S. production of motorcycles came in 1898. Also in the 1890s, a teenager in Northfield, Lincoln Fey, adapted bicycle parts as he experimented with auto invention at local bicycle shops. And bicycle mechanics Orville and Wilbur Wright worked on airplane creation in Dayton, Ohio, using bicycle technology.

One last personal note: This is the second time I have written about bicycling. The first time was when I was a columnist for our local newspaper in New York and my daughter Laurel, at age 7, was learning to ride a bike. So, of course, I wrote about it.

“How far away from home can you get on a tricycle?” I asked. “Ah, but a bicycle! Those two wheels can get you away from Mother’s eyes much farther and faster than three. So the romance with the bicycle begins…” Laurel’s inspiration was a neighbor boy named Dennis who had graduated from tricycle to bicycle (with training wheels). Her bicycle was pink with the name Sweet Thunder emblazoned on it and her prayers at night now included, “Help me to be a good girl, help me to ride my big bike up hills and down. Amen.” And although she was excited when she finally mastered the elusive balance, her enthusiasm was tempered by finding out that pedaling could involve work, especially on hills.

“It’s not fair!” she said. “It’s supposed to be fun.”

Laurel still rides a bicycle in San Francisco. I think it is mostly fun for her. And she has learned the lesson I ended my column with so many years ago in New York: “You cannot expect to coast through life. Sometimes you must also pedal.”

Thanks to Carleton College archivist Eric Hillemann, Rice County Historical Society executive director Sue Garwood, Ariel Butler of the Northfield Historical Society and Steele County Historical Society archives director Daniel Moeckly for their help with this story.

Bike Sites Beyond the Northfield Area

This list was published May 2014

-Faribault Flyers Bike Club, all levels

-Owatonna Bicycling Club, all levels, owatonnabikeclub.com

-Owatonna Mountain Bike Club, facebook.com/owatonnatrailsassociation

-Erik’s Riders Club, Burnsville, all levels, eriksbikeshop.com

-Silver Cycling, Lakeville, an official USCF Cycling Team, silvercycling.org

‘Tis the Month for Biking (May 2014)

Although more than half of the U.S. population lives within five miles of their workplace, lack of knowledge and incentive has deterred many from commuting by bike.

Sponsored by the League of American Bicyclists, Bike Month also features Bike to Work Week, May 12-16; Bike to Work Day, May 16; and Bike to School Day, May 7.

Non-Rules of the Gravel Road

By Nathan Nelson

Welch, Jeff Stremcha and Joe Pahr. Photo by Bruce Anderson.

They came into the Contented Cow one night bruised, battered, and in bike shorts. “Who are those guys?” I thought to myself. Wait, I know some of them. I’m used to seeing them clad in colorful lycra, climbing off expensive carbon fiber bikes fitted with the finest components money can buy. Usually, there’s a serious air as the ride is analyzed and dissected. There are a few laughs but mostly a lot of theories about the weight of bike parts and the effectiveness of the latest training methods.

Well, it’s the same guys but on this night but they look and act differently. They are full of dust, sweat and one guy is bloodied. They are not wearing the expensive bike clothes and they are riding beatup older bikes. They’ve also got headlamps on their bike helmets. Everything is dirt and dust. The effect of the dust and sunburns makes their teeth look unusually white. Yes, they look like miners but they act more like cowboys. They are doing a lot of laughing and even standing up as they tell their tall tales and drink their beers. They are gravel road bike riders.

I’ve done some of the group bike rides in Northfield on paved roads. There’s a lot of protocol, which is necessary for everyone to have a good time and not get in an accident. The goal is to ride in a tight pack to reduce wind resistance. You have to pay attention and it can be hard to keep up with the pack. Rides start on Bridge Square. Before the ride everyone is milling around and happy to share their bike knowledge. Don’t be fooled by the congeniality, though. Once you’re on the bike they would love nothing better then to push you into zones of pain that even Donald Rumsfeld would find cruel and unusual. It’s sneaky how it works. You’re keeping up with the group early and feeling good about yourself. Everyone is joking around and you feel part of the gang. After some miles you start hitting the hills by Cannon City or perhaps you enter Sogn Valley and if you’re not careful, you’ll get dropped like third period French.

When you’re dropped you have to battle the wind by yourself. You start talking to yourself and the words aren’t pretty. Forget it; if you are alone without the benefit of a drafting off someone, there is no way you can catch up to the group. It’s a lonely battle out there filled with regret, envy and a sore butt. When you see the guys and gals at the coffee shop later in the morning, they have been there awhile. Surprisingly, instead of gloating, they are happy to see you and full of encouragement. Road bikers admire anyone who is trying to get better.

I love gravel roads. I grew up in Forest Lake but we also had an 80-acre rundown farm 25 miles north by Harris. In the spring the frost would go out of the roads and with a little rain they became full of mud. We would get stuck in our ’68 Mercury Montego at the same bend in the road every year. In late summer, it would get sandy and washboardy. We would have to roll up the windows to keep the dust out but it would still come in through the back speakers and get on our clothes. My brothers and I did a lot of running, hiking, getting lost and looking for lost animals on the roads around the farm. We never rode bikes, though, because somebody told us that the gravel would ruin the gears.

So, what’s the deal with these gravel road riders? Are they working out deep psychological problems or do they simply like to play in the dirt? It was time to find out, so I contacted fellow Hamline alum Joe Pahr to see if he would let me ride with the gravel gang. He immediately thought it was a good idea, at which point I figured I was getting set up for pain or humiliation or both. I’ve heard the term “gravel gods” bandied about by bike riders but now I was thinking that it wasn’t just a joke and I was in for some serious rites of passage. What were they going to make me do to get initiated…steal chicken feed and try to jump a barbed wired fence?

The Ride

As usual we met at Bridge Square. Our group of nine had every type of bike there was. There were bikes specifically made for gravel, skinny road bikes fitted with knobby tires, mountain bikes, and a bike with tires so huge you could put them on a tractor. This particular April evening was the warmest day in six months and consequently everyone’s mood was way up. The chattiness was almost nonstop. Bruce Anderson came up with a great route for us. With a huge wind on our backs, we set off northeast out of Northfield. After riding on pavement for a few miles we hit the gravel and crossed Highway 19. We immediately spread out in a random fashion as we came into the valley of the Cannon River. The dirt on the road was hard and fast and there were some edges that you had to look out for. We went back and forth across several streams. We noticed the last few snowdrifts petering out in the ditches. There was quite a bit of talk about spring being the best time of the year to see things. In the winter the snow covers everything up and in summer there is so much foliage that you can’t see very far. But on an evening like this, far-off water towers, wind turbines, and college dorms glow in the setting sun.

Small groves of gnarly hardwood trees popped up everywhere. They encircled abandoned old farm buildings like they were slowly choking them out of existence. Each farmstead told a different story. There were beautifully manicured farms where everything looked coordinated and in synch and there were farms with no continuity at all, which had buildings and machinery from just about every decade.

About halfway through the ride, we stopped in a beautiful little cemetery on a slight height of land. We looked around and wondered what the original settlers might think of us riding long distances just to do it. Back on the bikes, we next came to an area that had black soil almost ready for planting and some intermittent pines. It was time to head back towards town. On the return we were somewhat protected from the headwinds by the valley of Cannon River. There was only one stretch of tough riding. We had to go uphill into the wind to get out of the valley. The two women riders in our group slipped through the wind with ease and got quite far ahead. Back on 19, it was just a few miles past Carleton and into town and the ride was over.

The good vibes continued after the ride on the deck of the Cow as Joe, Bruce, Mike, Jesse and I swapped stories. Joe said, “There aren’t a lot of rules on gravel and each ride is different. One time it might be a quick pace and everyone’s together and then the next time people are getting off the bikes to hike around and explore.” Mike told the story of a gravel race in Wisconsin where the riders had to carry their bikes through deep water across a flooded road. Joe and Bruce have done some 100 mile gravel races and plan to do more. At a gravel race there are few rules, just a start time and a map. Joe fondly recalled the teamwork involved in a cold and wet race called “The Heck of the North.” He and a friend had to work together to get through it.

I can think of no better way to experience the rural landscape than on a bike on a remote dirt road. It’s great as a solitary activity or with a bunch of friends. So is there anything wrong, you know, mentally with gravel riders? As it turned out, I was left with few clues as to their psychological make-up. They might be fairly normal. In fact, I think I’ll join them for some more rides, although I won’t be too shocked if things get a little weird.

Northfield: Bike Town, USA?

By Bruce Anderson

Northfield is well on its way to becoming what I would consider a bike town. Evidence that Northfield is developing into a great cycling community can be seen in the growing number of people bike commuting year-around, droves of people biking around town in nicer weather, large groups of spandex-clad riders heading out of town on road rides on Saturday mornings, regular gravel rides departing from Bridge Square in the evenings and the increasing number of bike races and events spring through fall. We’re by no means on a par with Amsterdam (or even Minneapolis, Portland, Davis or Boulder – yet), but Northfield is fast becoming a great place to ride a bike.

Northfield is well on its way to becoming what I would consider a bike town. Evidence that Northfield is developing into a great cycling community can be seen in the growing number of people bike commuting year-around, droves of people biking around town in nicer weather, large groups of spandex-clad riders heading out of town on road rides on Saturday mornings, regular gravel rides departing from Bridge Square in the evenings and the increasing number of bike races and events spring through fall. We’re by no means on a par with Amsterdam (or even Minneapolis, Portland, Davis or Boulder – yet), but Northfield is fast becoming a great place to ride a bike.

It hasn’t always been so. When my family moved to town in 1967, my Schwinn Sting-Ray was my freedom machine. I’d ride around town to school, baseball games, the pool, and to play with friends (even riding all the way out to Dennison once, a HUGE solo adventure for a 10-year-old). However, most of the bikes I would see around town as a kid in the late ’60s through late ’70s were ridden by other kids, with just the occasional adult being seen, such as the eccentric (because he was riding a bike?) elderly chap who rode his balloon tired bike around town slowly and lived in the Central Hotel (above today’s Rare Pair). When I did some road racing in the early ’80s, I would rarely, if ever, see other people when I was out on training rides, and no one else from Northfield, to my knowledge, was racing at that time.

Things changed, slowly, over time. When I moved back to Northfield in 1993 after living out of town for about a decade, I began seeing other road riders, and adults riding their bikes for transportation were a somewhat more common sight. In about 1995, I joined a few friends who had started doing regular Saturday morning road rides. Soon, the loose and informal Northfield Bike Club was born. Things really started picking up about 10 years later, as more and more people joined us, and more and more people were out riding their bikes in general. Bikes seemed not to be “just for kids” anymore, and bike commuters and other utilitarian riders were in evidence in increasing numbers, as well as an increased number of recreational (and racing) cyclists.

In about 2011, a new, somewhat more official local bike club, the Cannon Valley Velo Club, sprang up and began filling a need for regular, organized recreational rides both for those looking for long, vigorous rides and for those looking for something a little more relaxed. By the spring of 2014, two new bike advocacy groups had come into existence (BikeNorthfield and CROCT – Cannon River Offroad Cycling and Trails). BikeNorthfield’s mission is to work with community and regional partners to promote safe and convenient bicycling for transportation, recreation and tourism in and around Northfield. The mission of CROCT is to advocate, build, maintain and enjoy sustainable trails for offroad cycling and other recreational use. Other bike-related groups are active as well, including Mill Town Trails, working assiduously for many years to connect the Cannon Valley Trail (Cannon Falls to Red Wing) to the Sakatah Trail (Faribault to Mankato), and the Northfield Pedalers, a group of senior recreational cyclists.

Things aren’t perfect, as there remains a great need for improved cycling infrastructure in and around Northfield, but things have come a long way since I first tooled around town on my Sting-Ray. The townships surrounding Northfield are blessed with great gravel and asphalt roads for riding, and Northfield is the kind of compact community that lends itself well to getting around by bike. I’m hopeful that as a critical mass of cyclists of all persuasions grows in the community, Northfield will become a true bike town in the foreseeable future.

Resources:

-BikeNorthfield – facebook.com/BikeNorthfield

-Cannon Valley Velo Club – sites.google.com/site/cannonvalleyveloclub

-CROCT (Cannon Valley Offroad Cycling and Trails) – croct.org & facebook.com/Cannonriveroffroadcyclingtrails

-Tour de Save – facebook.com/pages/Tour-de-SAVE/188765119864

-Jesse James Bike Tour – jessejamesbiketour.org

Minnesota Gravel Championships – facebook.com/minnesotastategravelchamps

Bruce Anderson is an avid lifelong cyclist, the chair of BikeNorthfield and a member of the Cannon Valley Velo Club.