“We were built and now stand on the shoulders of Giants.” This was the shared sentiment of the St. Olaf College Department of Art in the wake of losses of Reidar Dittmann, Arch Leean and John Maakestad at the time of Maakestad’s passing this year. Dittmann, after whom the building housing the Art Department is named, died Dec. 29, 2010, Arch Leean on April 22, 2011, and Maakestad on April 10, 2012.

The Flaten Art Museum in the Dittmann Center opened an exhibit called “Artists on the Hill” last month featuring works of Leean, Maakestad, faculty emeriti A. Malcolm Gimse and Jan Shoger, along with present members of the department. The show of paintings, drawings, prints, textile, sculpture, ceramics, photography and video plus media combinations will run through Oct. 12. In addition, Leean’s highly praised series of 40 drawings based on The Book of the Revelation of John from 1980 will be featured from Oct. 26 through Dec. 2 at the Virginia and Jennifer C. Groot Gallery within the Dittmann Center. Maakestad’s son, artist Tom Maakestad, is putting together a joint show of their art at the Northfield Arts Guild that will run from Oct. 31 to Nov. 30.

The exhibitions will provide local residents with a unique opportunity to see the art of two of the “giants” of Manitou Heights who will be forever remembered by their students and colleagues. (See box at end for Arch Leean.)

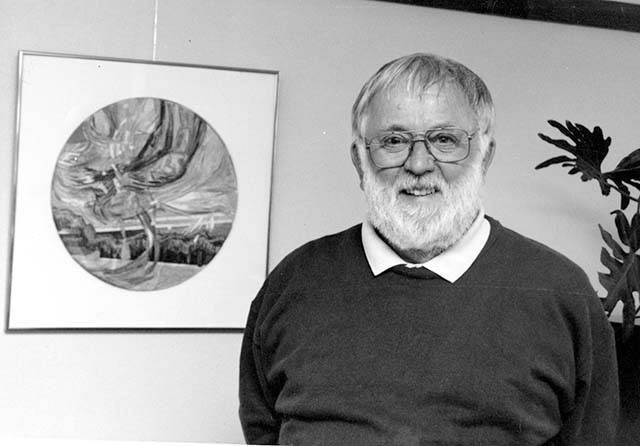

In 1979 John Maakestad was in a reflective mood as he talked to Robert Phelps of the St. Olaf News Bureau about a 30-year retrospective of his works which was opening at the college’s Steensland Gallery. He told Phelps, “Every once in a while, I think about doing something entirely different. But I know I never will. A long time ago, I made a commitment to being a professional artist and that’s what I am. I feel an obligation to keep moving and growing, and I have to believe I’m adding something to the world.”

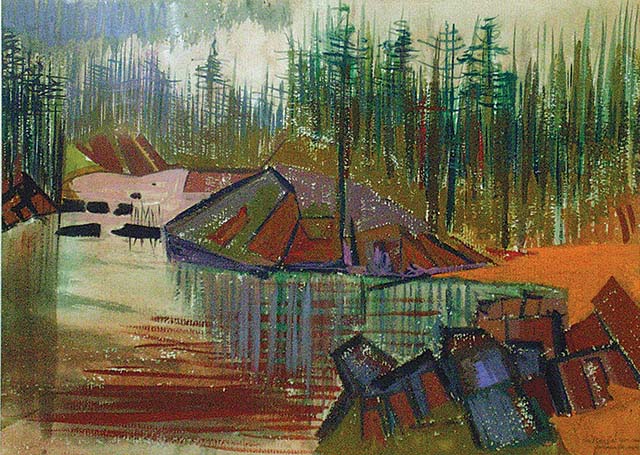

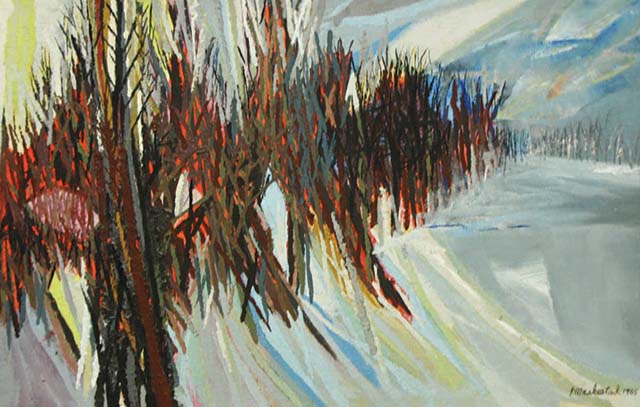

The retrospective included paintings, graphics and sculpture. The paintings, predominantly landscapes, were influenced by the “rolling countryside of southeastern Minnesota” and “the rugged grandeur of Washington’s Cascade mountain country,” places close to his heart.

Summers spent teaching art at the Lutheran retreat center of Washington’s Holden Village, wrote Phelps, “have promoted a love affair with that terrain which provides a contrast with his natural habitat.” Maakestad’s work became more abstract in the 1960s and Maakestad told Phelps that his most recent work was an attempt to make the invisible visible.

“I suppose that is what artists always try to do,” said Maakestad. “I’ve had this image of art as a rainbow between now and eternity – a way of making the things we feel concrete, to somehow make the feelings of the spirit tangible.” He described his style as starting with a “chaotic scribble,” and “then I try to impose an order on that with vivid colors.” His technique lately had been to “put strips of masking tape over the scribble and paint in color between the strips.” And when painting becomes tedious, “I change the medium – to drawing or sculpture.”

While this interview from 1979 focuses on his art, mention is made of his running, cross country skiing, riding his bicycle from his farm home near the edge of Nerstrand woods to campus – the types of pursuits which define Maakestad as much as his artistic life. In fact, he had just taken up bicycle racing and had won the 100-mile Defeat of Jesse James race that September which he had co-organized.

Maakestad came to St. Olaf College from Rochester, where his father was a Lutheran pastor. He graduated with a major in art and English in 1950. At St. Olaf, Maakestad was influenced by Arnold Flaten who had established the Art Department in 1932. Maakestad met his wife, Bobbie Shefveland, on campus and they were married in 1951. After serving in the U.S. Army, he earned a Master of Fine Arts degree in 1955 from the University of Iowa with an emphasis in studio art and art history.

Maakestad joined the St. Olaf art faculty in 1956, teaching painting, drawing, design, printmaking, sculpture and art history, coordinating college exhibitions and collections and designing sets for the St. Olaf Christmas festival for 20 years through 1977. Mac Gimse, now professor emeritus of the St. Olaf Art Department, recalled the designs which sparkled with “the oddest details, like cardboard wrapped in aluminum foil, which moved in the slightest air and reflected the tiniest light. His double dodecahedron stars, ingeniously hot-glued together and hung in Skoglund gym, out-dazzled the greatest ballroom.” Maakestad once said he considered his festival work, which he kept and stored in his barn for many years, as some of his best art, seen by almost 100,000 people.

In 1968, Maakestad began the first of eight years as chair of the Art Department and, in 1969, he started summers of teaching at Holden Village in Chelan, Washington, and began mountain climbing. Near Nerstrand, he became heavily involved in the Society for the Preservation of the Valley Grove Church Building. Saved from being razed, the church had a celebration of its 150th anniversary last month.

On Oct. 4,1983, the St. Paul Dispatch took note of a “Maakestad Family Show and Tell” exhibit at the Northfield Arts Guild Gallery where six Maakestads, led by “Papa John” with his landscapes, displayed 71 pieces of art in a variety of mediums and styles. John’s wife, Bobbie, wove poetry into quilts and tapestries. The oldest son, Erik, then teaching sculpture at the University of Illinois, exhibited sculpture in clay and steel and mixed media in the show, while his wife, Susan, showed her oil paintings. Jon, then on the staff at the Walker in Minneapolis and at galleries in Washington, D.C., showed some of his cherry wood and walnut carvings influenced by Flaten. Tom, a free-lance graphic designer who had studied at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design, showed water colors. John Maakestad said that their youngest son Rolf, a junior at Luther College, was the only “maverick” not represented.

Maakestad told the reporter, “I always tell people, jokingly, that I stood behind each one with a baseball bat and said, ‘Paint or sculpt, darn you.’” What really happened, he said, was, “We gave them crayons, paper, paints and clay and let them ruin the house and clutter it up with all the messy stuff they could.”

One of Maakestad’s sabbaticals was the topic of the Manitou Messenger of Oct. 31, 1986. He had researched modern, Renaissance and baroque art, “looking for women artists and the presentation of women in Western European art,” having noticed that only a few women artists were mentioned in major art textbooks. Maakestad felt the need “to give more recognition to women and their contributions,” Jan Shoger told me. He began teaching a “Women in Visual Arts” seminar in 1986. Shoger (who was chair of the Art Department from 1991 to 1994, taught at St. Olaf for 20 years and is now professor emeritus) said that “people responded so well that we eventually added it to the curriculum.”

Shoger provided me with an example of Maakestad’s teaching style. When he would teach a 20th century art history course, the room was darkened in order to show slides of the works.

“We called art history courses Art in the Dark,” said Shoger. “Especially if the class was after lunch, he would find students falling asleep, dozing off. Often if he saw two or three falling asleep, he would say, ‘Now this next oil painting is done by Mickey Mouse’ and he would go on and talk about the art method and the rest of the class would laugh. So that would wake up the student who was sleeping. He could go back and say ‘Oh, I think I misspoke. It wasn’t Mickey Mouse after all.’ He tried humorous things to get the kids to stay with him in Art in the Dark.”

Artist Jill Ewald, director of the Flaten Art Museum for the past decade, came to study at St. Olaf as an adult in 1985 and “just wanted to make art,” not study art history. At his memorial, she said, “Then I took art history from John, who made it come alive. Every artist/art period/architecture he talked about was in a greater context that connected cultures, worlds, times. He opened my mind and eyes. He taught me to love art history as part of art making. And to embrace life. Gentle, funny, thoughtful man.”

The summer of 1987 was highlighted by an adventure which took place after the annual stay at Holden Village. A headline in the Northfield News of Aug. 20, 1987, read, “Maakestad Bikes 2,000 Miles on Cross-Country Trip,” from Washington to Nerstrand. Bobbie Maakestad told me at the opening of the current art exhibit at St. Olaf that her husband had talked of doing this so often that “I called his bluff and insisted he do it.” He had told the reporter, “When Bobbie left for home, she left me standing by the side of the road. I watched her drive away – and I cried!” She drove home in three days; he biked it in 21 days, riding over mountain ranges and using back roads as much as possible. Shoger recalled hearing that if he stopped beside the road for tire repairs, passersby would offer to help and end up inviting him for a meal and to stay overnight. The News story said that at Whitefish, Montana, a host “barbecued a moose roast in his honor.” He rode with three other bikers through Montana and North Dakota, encountering 104 degrees and a headwind at Williston, N.D. Bobbie Maakestad told me that the “most fun” he had was “being able to say he had done it.”

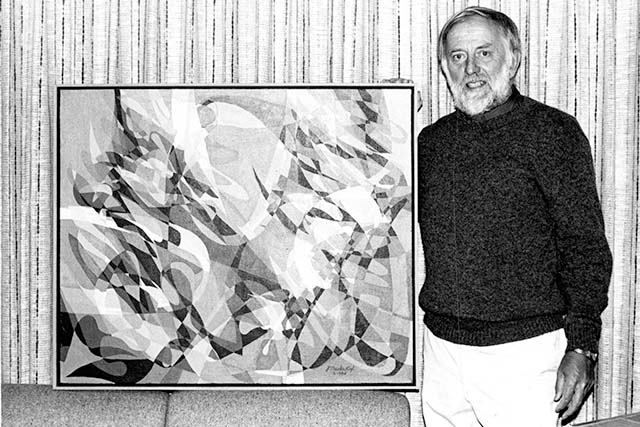

A retrospective of Maakestad’s art opened at St. Olaf’s Steensland Gallery on Jan. 15, 1994, in anticipation of his coming retirement after 37 years of teaching. Pieces included oil on canvas, oil pastel on paper, mixed media, acrylic on canvas and ink on paper. Shoger told me that Maakestad chose the title of this exhibit: “A Pilgrimage: I’ll Tell You Where I’m Going When I Get There.” She explained, “John was a really curious and inventive person who was so comfortable with changing media. His hiking in the Cascades were his own pilgrimages. He felt deeply, spiritually, that life was a journey to carry out some new ideas, that he never knew exactly where it was going to take him next. He was always open to something new that was coming up.”

The booklet for the exhibit provided the opportunity for Mac Gimse (who had been hired by Maakestad in 1970) to write about his colleague.

“John Maakestad has the largest brain of anyone I have ever known. Yes, his head takes an unusually large hat, but I am referring to his brain power. He has enormous storage capacity that updates itself by going from the old file folders to microchip memory….John has the rare synaptic power to bring back images and ideas in combinations that dazzle a lesser mind.”

Gimse also wrote of how Maakestad was imbued with “outside air.” Nature envelops him, but “it is a spiritual nature as he conceives it. The world is alive with a glow even in the dead of winter.” Landscapes “unfold in sketches as he walks through them,” and “prairie vistas almost roll onto paper as he rides his bicycle across Nebraska. Mountains and glaciers cascade from his pen.” Gimse concluded, “When we join him at his artist’s table, he serves us his love of nature as the bread of human existence. His cup gives off the aroma of spiritual insight that baffles us in its execution, but inspires us by its energy and other-worldly origins. Thank you, John, for being our host at this latest feast!”

A feast of another kind took place at the retirement party for Maakestad. Shoger told me that they had a party catered at the Minnesota Zoo after its closing hours. Invitations went out to colleagues and art majors, past and present, with instructions to come in animal costumes.

“Ed Sovik and his wife came as toucan birds with great big beaks, Mac Gimse came as a gorilla,” said Shoger. There were perhaps 250 people at the dinner. There also was an opportunity to hold iguanas, rabbits and so on in the “feel and touch room” and they had a “This is Your Life, John” showing of more than 100 slides put together with the help of his wife, Bobbie. Shoger said, “It was one of the best parties we had for the Art Department and John really enjoyed it.”

In the first autumn of Maakestad’s retirement, he made a series of pen and ink drawings of the Nerstrand Big Woods which he showed in a Northfield Arts Guild exhibit with his daughter-in-law Susan. In a Northfield News story of Feb. 9, 1996, he described how he drew trees, after photographing them: “Trees are added and subtracted at will. They bend to converse with each other and some old maples are hard of hearing. Some younger trees get restless and start rocking a bit.”

Maakestad was in the Northfield News again on May 30, 1997, as a result of a horrific van explosion in Apple Valley. The interior of the van burst into flames when a “gas can sitting in the rear passenger area tipped over and ignited. Maakestad was burned so quickly and seriously he could not escape from the vehicle. A passing driver pulled him out and saved his life. Within seconds, the empty vehicle coasted to a curb where it exploded.” His burns covered over 20 percent of his body and grafts for third-degree burns were necessary.

Shoger told me his recovery was “long and difficult,” but he developed a “real camaraderie” with other patients in the burn unit and during rehabilitation after skin grafts. “He really felt he had been given a second life, he felt completely renewed and energized” and threw himself into his art work with renewed vigor. He continued to have many art shows, including through his last year.

On April 10, 2012, Maakestad completed his life’s pilgrimage, dying of pneumonia at the age of 83 while visiting in Arkansas with his wife Bobbie. Bobbie Maakestad told the Star Tribune of April 14, 2012, that hearing from his former students “gave him the most joy, knowing that something he did enriched their lives.”

I asked L.K. Hanson, St. Olaf Class of 1966, to say a few words about his mentor. Hanson, long-time artist of the Star Tribune who still has a regular Monday Opinion Exchange feature called “You Don’t Say,” responded: “John was my faculty adviser when I started at St. Olaf in 1962. I was 19, literally straight off the farm. Never had an art class. Never met a real artist. More than anything else, I will forever remember John as a warm guiding presence in my artistic and creative development. We were, in some ineffable way, kindred spirits; brothers in artistic sensibility, in outlook and in sly mischief-making. He encouraged me when I started doing ‘The Uglies’ cartoon strip in the Mess, and was ever the enduring fan.”

When Hanson encountered difficulties his sophomore year, Maakestad “urged me to continue at St. Olaf, telling me that I could be the artist I wanted to be if I was willing to do the work. Over the years, we stayed in touch. Throughout his later life, John was unfailing in his interest in my creative efforts, always encouraging, always ready with a Maakestadian observation. He holds a special place in my heart – and always will – as a testimony to the power of art and of enduring friendship.”

At the funeral service at St. John’s Lutheran Church in Northfield on April 21, Wendell Arneson (who joined the St. Olaf art faculty in 1978 as a sabbatical replacement for Maakestad) quoted Dr. Seuss: “Don’t cry because it’s over, smile because it happened.” Arneson said of Maakestad, “Always a kind word, wisdom, and twinkle when sharing advice…Many of our lives here today have changed in subtle, endearing, and sensitive ways because of the life journey of John Maakestad…He has always filled my heart with immeasurable love, respect and admiration. Thank you, John. We, I, will smile because you happened.”

Thanks for assistance with this story to Jeff Sauve, Jill Ewald, Jan Shoger, Wendell Arneson, L.K. Hanson and Tom Maakestad.

Arch Leean: From Flintstones to Fusions

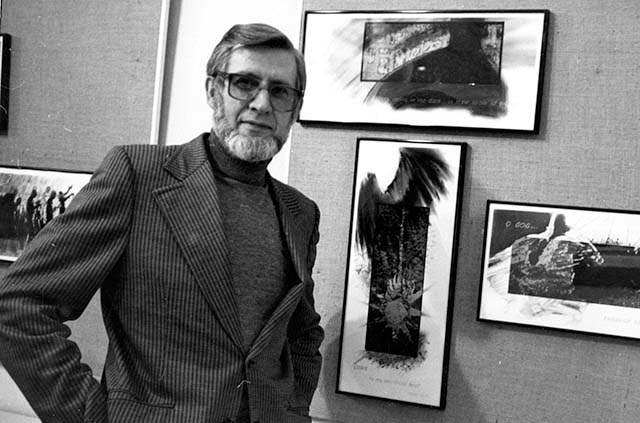

“Yabba Dabba Doo!“ People of a certain age remember the catch phrase of the “The Flintstones,” a stone-age family from Bedrock. Arch Leean, a Wisconsin native, worked as a film animator from 1957 to 1964 for California studios such as Hanna Barbera of “Flintstones” fame, Walt Disney and Jay Ward (“Fractured Fairytales”) before coming to St. Olaf to teach art from 1964-1993.

The exhibit booklet from “Artists on the Hill” (at the Flaten Museum through Oct. 12) lists Leean’s artistic activity of “documentary, animation and live action films, drawings, paintings, computer enhanced drawings and prints and sculpture.” Two works from his 1980 Revelation Series at this exhibit will be followed by the complete series of 40 drawings in the Groot Gallery Oct. 26-Dec. 2.

Leean said that The Book of the Revelation of John has to be “one of the most visually fascinating accounts ever written. It begs for interpretation, yet it rewards one who only reads or listens to the story…I hope the process of combining visuals and words can also provide assistance to the reader or listener who wants to become more familiar with the book without pretending to understand all that it contains.”

At a faculty reception upon his retirement in May of 1993, Art Department chair Jan Shoger praised him as “a person who has kept alive the tradition of Arne Flaten, who founded the St. Olaf Art Department; an enormously inventive, creative man; a man who with his gentle manner has reached and inspired many, many students.” Among his many accomplishments: establishing the first color graphics computer lab. Shoger told me that because of Leean’s knowledge, St. Olaf had computer courses in the studio art department ahead of other colleges and universities, with “eager students that wanted to find out about this new equipment.” Among his independent films was “Fusions,” a computer film with dance and electronic music which was presented from 1982-86 in Minneapolis, Northridge and Los Angeles, Kansas City and Portland, Oregon. Leean was chair of the Art Department from 1978-83.

Leean and his wife Mary, who became assistant director of foreign student services, led international studies terms in the Far and Near East in 1974 and 1983. He had met his wife when she was a secretary for St. Olaf’s Dean of Women, Gertrude Hilleboe. He was then working for the Ed Sovik-Arnold Flaten architectural firm and taught art classes with them at St. Olaf from 1953-54 after graduation from the Univ. of Wisconsin and two years as an Air Force pilot. The Leeans were married in 1955 in London, where he was studying at the Slade School of Art. Leean made films for teaching purposes at a Lutheran retreat center for Iron Curtain refugees in England which sparked an interest in this medium and led to a master’s at Columbia University in film and then at the Univ. of S. California in animation. After seven years working in animation, he returned to academia at St. Olaf in 1964.

After retirement in 1993, the Leeans moved to Reed Springs, Missouri, near Branson, where they had built a “dream house.” After a three-year struggle with a rare degenerative brain disorder, Leean passed away on April 22, 2011.

Among the memories shared at Leean’s memorial service in Missouri was one from a former St. Olaf art student: “Arch’s figure drawing classes showed me to see and draw critically and intelligently. My recent ‘Arch moment,’ however, was when my 10-year-old son asked me to teach him how to animate a Calvin and Hobbes comic. My son and I spent a weekend working out the story, drawing, photographing and compiling all the images…because I had the honor of knowing a great man who taught me magic.”