“Robbery & Murder!” screamed the headline of the Rice County Journal of Sept. 7, 1876. “Desperate Attempt to Rob the Bank! J.L. Heywood Shot Dead at His Post – Would not open the Safe.” The time of this “extra” edition was given as 4 p.m., a scant two hours after the James-Younger Gang’s brazen attack on the First National Bank which propelled Northfield, Minnesota, into national and international fame as the Waterloo of the outlaws.

“Robbery & Murder!” screamed the headline of the Rice County Journal of Sept. 7, 1876. “Desperate Attempt to Rob the Bank! J.L. Heywood Shot Dead at His Post – Would not open the Safe.” The time of this “extra” edition was given as 4 p.m., a scant two hours after the James-Younger Gang’s brazen attack on the First National Bank which propelled Northfield, Minnesota, into national and international fame as the Waterloo of the outlaws.

In the story, editor Charles A. Wheaton wrote that he was at work getting the paper off when his attention was “arrested by the discharge of firearms across the street at the corner, and all around the Scriver Block and covering the First National Bank.” Eight or ten horsemen, “armed to the teeth with heavy revolvers,” were “discharging them in rapid succession” with the citizens “flying in all directions.” Inside the bank, the robbers shot acting cashier Joseph Lee Heywood dead and wounded teller A.E. Bunker in the shoulder while outside “our citizens began to rally, and to return their fire,” killing two of the robbers and one horse. This “reception” was so hot that the raiders “turned and fled south, dashing through Dundas towards Millersburg with some of our good men in pursuit.”

The story continued in the Extra datelined Sept. 8: “Our usually quiet little city was uncommonly wakeful through the night of Thursday, the 7th, after the tragic events of the preceding afternoon. Our streets are filled with anxious faces and open ears to catch every rumor from the flying robbers and their determined pursuers.” The article detailed the actions of a coroner from Faribault and the content of telegrams arriving in the wake of the robbery, including a request from the Chicago Times for “1500 words over the wires” to “represent the facts of the raid.”

Presaging the future renown that would come to the town, Wheaton wrote: “Right here we remark that this is the first instance we think of in any similar raid, that any of the robber gang were killed, and Northfield is entitled to the credit of putting two of the raiders hors du combat, and seriously wounding two more, besides killing a splendid and innocent horse, which was made subservient to their villainy. Let us put the horse in his own peaceful heaven. He looked like a thorough bred.”

A description of the dead robbers and their wounds was given. The photographers “have made good pictures of these desperadoes for the use of the rogues gallery, or for sale to those who have no such gallery,” Wheaton said. (These pictures are still for sale today as postcards. It has been estimated that after the raid Minnesota photographers Ira Sumner, Elias Everett and William Jacoby sold nearly 50,000 souvenir sets of pictures of the deceased raiders.) This story also took note of the condition of Nicolaus Gustavson, a Swede struck by “reckless shooting of the desperadoes,” whose symptoms were “quite serious if not dangerous.” Indeed, Gustavson became the fourth casualty of the raid.

Wheaton wrote that “in their hurry, as it was getting hot for them outside,” the robbers had fled the bank leaving a grain sack of nickels and scrip and a linen duster behind. He commented parenthetically, “Probably the Bank would send these by Express, if they can get their address.”

On Sept. 14, a full account of what was called “The Northfield Tragedy of Sept. 7” appeared in the Rice County Journal with a drawing based on Sumner’s death photos of two robbers, though they were misidentified. What follows in this Historic Happenings column is based on Wheaton’s articles and first-hand remembrances of the participants from the Northfield News of July 10, 1897, and from Carleton professor George Huntington’s book Robber and Hero, first published in 1895.

At about 2 p.m., three of the outlaws went into the bank. Hardware store owner J.S. Allen, whose suspicions had been aroused, attempted to follow and Clell Miller, on guard at the door, grabbed Allen by the collar, drew his revolver and told Allen not to holler or “I’ll blow your damned head off.” Allen jerked himself free and ran toward the corner crying, “Get your guns, boys, they’re robbing the bank!”

Inside the bank, clerk Frank Wilcox said he was “more than startled” by three men with pistols in their hands (later identified as Bob Younger, Charlie Pitts and Frank James), one of whom shouted, “Throw up your hands! We are going to rob the bank.” They claimed they had 40 men outside so resistance was useless. Wilcox said, “It was very evident that they had been drinking as the smell of liquor was very strong.” On the day of the raid, Wheaton wrote, four of the robbers had wine or whiskey at local establishments.

The outlaws asked for the cashier and demanded the safe inside the vault be opened. Heywood, a bookkeeper substituting as cashier that day, told them, “There is a time lock and it can’t be opened now.” (In reality, the combination dial was not turned.) Pitts stepped into the vault and Wilcox said that Heywood, “probably with the thought of protecting the contents sprang to the vault door and partly closed it but was at once seized and dragged away.”

“Murder!” Heywood shouted. One of the intruders struck him to the floor with a heavy blow from the butt of a pistol. At that point, Pitts pulled out a knife, drew Heywood’s head back and said, “Let’s cut his throat.” Heywood’s throat was scratched by the blade and then, said Wilcox, “to further intimidate him a shot was fired over his head.” The demand to open the safe was repeated but, despite the rough treatment, Heywood “would rather sacrifice his life than betray his trust,” in the words of Wilcox.

Bunker made a break for the door, pursued by Pitts, who fired two shots at him. The second shot struck Bunker in the shoulder as he fled to safety. Increasingly frustrated, the robbers grabbed only a handful of cash and coins, missing the cashier’s drawer which had $3,000 in it.

Wheaton wrote that meanwhile, outside the bank, the firing on the street by the horsemen (Jesse James, Bill Chadwell, Clell Miller and Cole and Jim Younger) was meant to “scare our people so that they would get out of the way and let them accomplish their hellish deed.” But rather than just running for cover, many of the citizens ran to arm themselves. Henry Wheeler, a University of Michigan medical student home on vacation, had been sitting in front of his father’s drugstore across the street from the bank. When the shooting started, he grabbed an old army carbine he remembered seeing at the nearby Dampier House and positioned himself at an upstairs window of the hotel. He fired a shot which struck Clell Miller in the “region of the heart,” wrote Wheaton, “making him bite the dust” as he fell from his horse.

Three times Cole Younger exhorted the robbers to leave the bank, crying, “For God’s sake, come out; they are shooting us all to pieces!” Pitts and Bob Younger exited first. Frank James hesitated for an instant and then he turned “like a flash, and with the expression of a very devil in his face put his pistol almost at Heywood’s head and fired the fatal shot,” recalled Wilcox. Wheaton wrote, “They shot him and ran like base cowards.” Wheeler then aided A.R. Manning in a fight with Bob Younger who was exchanging fire with Manning while dodging back and forth under the Scriver Building staircase. (Bob was on foot since Manning had killed his horse. Manning later said that he supposed the robbers came to “sack the town” before they left and were using their horses as “breastworks,” or barriers to shoot from behind.) Manning, who was equipped with a 45/70 Rolling Block Remington taken from the window of his hardware store, said, “While we were thus playing hide and seek Wheeler struck him [Bob Younger] in the elbow.” Manning had shot Bill Chadwell dead from off his horse and also wounded Cole Younger in the hip. Storekeeper H.B. Gress later said Manning seemed to be the leader in the gunfight and “displayed more real nerve than all the robbers put together.” Gress added that all the shootings “produced such a concussion that frame buildings shook like trees would on a windy day.”

“For God’s sake, don’t leave me, boys, I’m shot,” Bob Younger called out. Cole pulled his brother Bob up behind him on his horse and the remaining gang members then galloped out of town, leaving more than $15,000 in the bank and two of their accomplices dead.

The Rice County Journal of Sept. 14, 1876, reported, “The Governor has issued a new proclamation offering $1,000 each for the bandits, dead or alive, and the Bank at Northfield offers $500 for each. If these offers do not increase the excitement, they do not diminish it.” After the largest manhunt in the U.S., four of the outlaws – the three Younger brothers and Charlie Pitts – were cornered on Sept. 21 in Hanska Slough near Madelia and in the resulting battle Pitts was killed. Frank and Jesse James had split from the others and made their way back to Missouri but the James-Younger Gang’s long reign of robberies had ended on Division Street in Northfield.

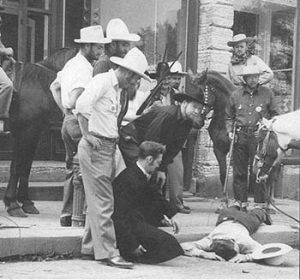

Northfield held the first reenactment of the bank raid on Sept. 11, 1948, as part of a fall festival. The Defeat of Jesse James Days are now held on the weekend after Labor Day, attracting up to 250,000 visitors over the five-day period. It is the largest all-volunteer event in Minnesota.

Rather than glorifying the bank raiders, the event seeks to emphasize the heroism of a town which rose up against the outlaws. On Sept. 7, 1876, indignant Northfield residents even threw rocks at the James-Younger Gang members as they fled in ignominious disarray.

The Northfield Historical Society offers tours of the restored site of the First National Bank raid at 408 Division St. For further information, see northfieldhistory.org.

Thanks to current James-Younger Gang leader Chip DeMann for assistance with this column. This story was originally published in the Entertainment Guide of September 2011.