“What most typifies spring?” asked a writer in the Carletonian paper on April 6, 1965. “Is it the girls seductively sunning themselves on Myers Hill? Is it the extra help being taken on by the Muni?…The real sign of spring is to be found only on the softball field. The Marvin Rotblatt League is readying itself for its second year of operation.”

Although the league is no more, a marathon 145-inning softball game with the Rotblatt name will be played on May 14 by Carleton students, one inning for every year since the founding of the college in 1866. The expressive moniker has been revered in Carleton lore for many years.

Back in 1964, a winter of discontent was settling in on sophomores Bob Greenberg, Eric Carlson and Rick Chap. The Continental Softball League, which had been organized the previous year and was now dominated by juniors, had spurned their efforts to join. So they met in a Burton dorm room, intent on devising a way to have a league of their own so they too could play organized softball games in the spring. In the weeks that followed, team captains were chosen and players drafted from among sophomores and a few juniors and seniors.

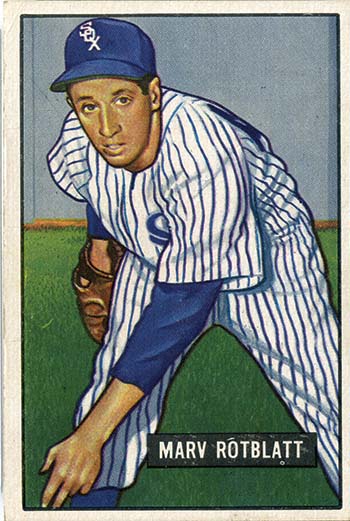

But what to call the new league? Chap came up with a Homeric home run of a name. Chap’s father had grown up on the south side of Chicago and passed along his White Sox fanaticism to his son, who knew names and stats of all players, including a pitcher named Marvin J. Rotblatt. In an e-mail, Chap told me, “I thought the name Rotblatt was unique and somehow descriptive for the kind of league we envisioned.” How so? Well, besides having an unforgettable last name, Rotblatt had achieved the highest earned run average in major league baseball for two of the three seasons in which he pitched: 7.85 ERA in 1948 and 6.23 ERA in 1950. He was also zero for 15 in career at-bats. As Bob Moore (’66), captain of the Rotblatt Maggots team, once said (famously and rather facetiously), “We needed a name to reflect what we were, the worst softball league in history. We were rejects in a small college that didn’t emphasize athletes anyway.”

Franchises were granted to four new teams and announced in the Carletonian of March 4, 1964, as the Marvin Rotblatt Softball League. Carlson was chosen as the league’s first Commissioner and, reflecting on the beginnings in the Carletonian of April 14, 1966, he said the new league had been started “to give all the Carls a chance to play softball in the spring instead of spending all their time in the Arb.” Since the Continental League “didn’t want to let the good guys in,” he said, “we had our own player draft and since then we’ve been the major league on campus.”

Well, not quite that fast. “Sugar Kings Squash Warthogs; Win First Softball Championship” was the headline in the Carletonian of June 3, 1964, reporting on the best of three World Series won by the Continental League champion Havana Sugar Kings over the Rotblatt League champion Warthogs (6-3, 3-4 and 4-1). Greenberg’s ability to balance a baseball bat on his nose did not appear to give enough of an advantage to his Warthogs team.

However, the Continental League expired after the spring of 1966, by which time the conquering Rotblatt League had ten teams in two divisions, with 13 players on each team, playing two or three times a week. There were official scorers and Greenberg told me, “Nearly all Rotblatt players took pride in their statistics.” Hal Hart (’67) recalled calculating stats on teams and team members his senior year on an old IBM 1620 computer. Hart, who became perhaps the first Carleton alum to earn an advanced degree in the new field of computer sciences at Purdue, found the results were eagerly awaited by ’Blatters, then were much discussed and dissected. The Carletonian glorified the league, giving it a lot of coverage as “Rotblatt Blather,” often to the disgruntlement of athletes in other sports. In 1967 PE credit was given for Rotblatt participation, until 1984. By 1970, the league had expanded to 24 teams and 300 players.

Freshmen were excluded, with the idea that they needed a year to settle into college life academically. Brenda Ringwald (’67) recalled the role of women was “to watch, bring snacks, tend to wounded bodies and egos, and listen quietly with the requisite amount of admiration when they would tell their Rotblatt stories.” (A “Wombat” woman’s league was added in 1975.)

A highlight of the early years came at the trophy banquet on May 28, 1966, when Marv Rotblatt himself was the guest speaker. Greenberg had volunteered to try to find Rotblatt in Chicago over the 1965 Christmas break and, he said, “Imagine my delight when I checked in that pre-Google source of information, the telephone book, and found he lived only a little over a mile from my parents.” A phone call and visit to Rotblatt’s home resulted. The former major leaguer was mystified and amused that a softball league was named after him at a small college a decade after he had left the pros to become an insurance salesman. Nevertheless, he agreed to come to Northfield in the spring for an all-star game and banquet in his honor.

Greenberg and Carlson picked Rotblatt up at the Minneapolis train station. Rotblatt looked like someone out of Central Casting, wearing a sport shirt and sunglasses, carrying a White Sox traveling bag, baseball glove and a trademark big cigar. They took him to a room at the Stuart Hotel (now the Archer House). On campus, a trombone player saluted him by playing “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” and Rotblatt’s arrival in the Goodhue dining hall for lunch was greeted with a standing ovation. That afternoon he pitched for the Rotblatt All Stars against a faculty team. Marvelous Marv entertained the large crowd with some behind-the-back throwing and (even though he never got a hit with the White Sox) by switch-hitting home runs, including a home run at his first at-bat. A WCCO film crew was there to cover the event. It was said that Rotblatt enjoyed joking and mingling with the students, especially the co-eds. He also put in a few plugs for Carls to remember his insurance business when they “reap the riches of the world.” The All Stars won 17-11.

At the Great Hall banquet, “Marv regaled the audience with tales of exploits from the University of Illinois to his days with the Sox,” said Greenberg, including striking out the great Ted Williams the first time he faced him. Rotblatt also told off-color stories which left the college men in stitches and Carleton President Nason turning different shades of red. Rotblatt was given a trophy, inscribed to “Marvin Rotblatt, Founder and Hero, Carleton College Rotblatt League, 1966.” All in all, said Greenberg, “It was one of the funniest and most enjoyable evenings I’ve ever experienced.” Rotblatt returned for the 1967 banquet and several times thereafter.

Carleton was celebrating its centennial in the 1966-67 school year and Rotblatters were involved in two of the commemorative events. Ted Lutz ’67 (who was plucked from Rotblatt to play varsity baseball) took part with Rotblatt players and others in a stunt to bat a baseball from Northfield to Metropolitan Stadium in Bloomington (current site of Mall of America) for a Twins game on May 22. Lutz e-mailed me about the implausible but true scenario of nine guys, with two station wagons being driven along rural Minnesota roads, with the men hitting balls in fungo fashion over and over for 10 or 11 hours.

“We had guys retrieving the ball from cow pens, farm machinery, etc.,” Lutz said, and they arrived at the Met during rush hour. After a buffet in the Stadium Club, he remembered “fungoing the ball from the outfield fence to home plate about 15 minutes before the start of the game.” The players, Carleton President John Nason (and perpetual icon Schiller) presented a Carleton rocking chair to Twins’ owner Cal Griffith, who had invited 1200 students and faculty to be his guests in honor of the college’s centennial.

Lutz was official scorekeeper for another memorable centennial event that spring, a 100-inning Rotblatt softball game held on May 16. There were 10 seniors per team, each playing 10 innings at 10 fielding positions. The game started at 6 a.m. and lasted nine hours with the teams battling to a fitting centenary final score of Sots 100, Dirty Old Men 81.

A Minneapolis Tribune story about the Rotblatt League on May 27, 1980, said there were now 580 players on 36 teams and an all-school picnic had replaced the Rotblatt banquet. The importance of keeping statistics was lessening and the game was played mostly for fun. There were reports of a team which would run bases in reverse order to confuse their opponents. Slingshots came into some prominence. One team pelted other teams with water balloons shot from slingshots, while the April 15, 1977, Carleton Daily announced that the first pitch of the season opener “will be a fast ball – fired from atop the library by a high-powered slingshot.”

According to Carleton archivist Eric Hillemann, Rotblatt as a league peaked in the 1970s into the 1980s. The character of the game changed and “transformed into an increasingly sudsy form of beer ball” and “eventually, true Rotblatt disappeared from the Carleton scene entirely (apart from reunions), with the exception of the single marathon game each spring.”

A few early Rotblatters commented on what has happened to the game they loved. Carlson, who said his extended family with wife Mimi contains 23 Carleton alumni, noted that the transition to “beer ball/longest keg party” was not “in the original plan.” But the idea was for Rotblatt to be “for the participants, so I guess the change reflects what they want.” Greenberg said, “I am happy that the Rotblatt tradition goes on in memory and that current Carls have a good time with it.” Nevertheless, “students cannot imagine how seriously we took Rotblatt Ball. It is like a religious event that has evolved over the years into a carnival.”

Hart also was glad that Rotblatt softball lives on but is disappointed that it has “devolved so far from the original simultaneously fun-but-serious, stats-conscious, competitive spirit of the Rotblatt League.” Yet, even though the one-day-a-year game “doesn’t do justice to the legacy for me,” he admitted he donated some money years ago for T-shirts and “probably would again if asked.”

Greenberg added that he understands how such changes happen. Echoing the writer in the Carletonian who asked “What most typifies spring?” he summed up his feelings: “Rotblatt was our rite of springtime and, after the long winters of Northfield, it was a fantastic experience.”

My thanks to Eric Hillemann and Carol Thunem of the Carleton Archives and all those who responded to my e-mails asking for help in writing about the Rotblatt experience. Particularly useful in the Archives has been Don Rawitsch’s “Definitive History of the Marvin J. Rotblatt Memorial Softball League” (Rawitsch, ’72, was among the developers of a well-known computer game called “Oregon Trail”).