It’s not too likely that the University of Minnesota will book Carleton as an opponent at its new TCF Bank Stadium. But Carleton’s football team played at home against the University of Minnesota in 1883 and won by a score of 4-2. (There were no safeties involved in that score. Goals were then worth two points and the game, in the process of evolving from soccer and rugby, was much different.) The year before, Carleton had a chance to be involved in the first football game ever played by the University of Minnesota. Teams from the University of Minnesota, Carleton and Hamline were to take part in a “Field Day” at the Col. King State Fairgrounds in South Minneapolis on Sept. 29, 1882. When Carleton failed to show up, Hamline ended up playing football against the larger school, losing 4-0 but gaining the distinction of being the University’s first opponent.

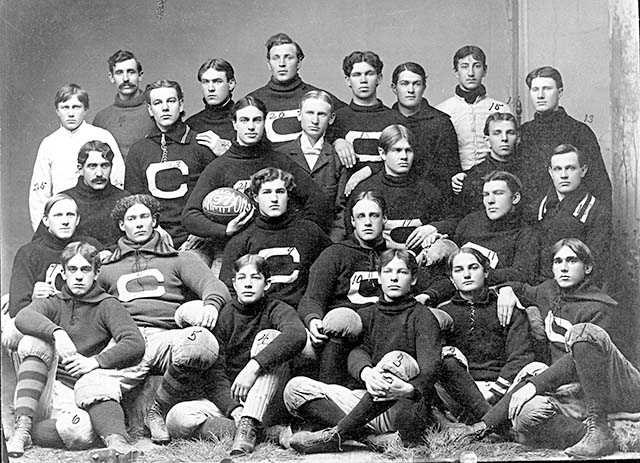

Although an unofficial football program was present at Carleton in 1883, the first officially sanctioned team was established in 1891 when Carleton won two games against Seabury Seminary of Faribault. Among the unofficial games were two tie games against the “St. Olaf Kickers” in October of 1887. According to long-time Carleton coach, Bob Sullivan, in “Knights of the Gridiron: A History of Carleton Football 1883-2005,” Carleton played 37 football games between 1883 and 1897, with a record of 22-14-1. Their 1898-1902 record was 25-13-2, including five losses to the University of Minnesota.

But football did not gain a hold at either college right away. In June of 1880, the editor of Carletonia wrote, “Athletic sports do not flourish at Carleton. At the beginning of this term a football game was organized, but after a brief existence its little candle went out…Leapfrog was for a time all the rage, but as warm weather came it too was voted too exhausting.” In the Manitou Messenger of October, 1891, C.M. Wesing wrote, “A Plea for Foot Ball,” saying that “the goddess of base ball seems to have fascinated all, and her worshipers cling to her with a tenacity which allows them practically no time for foot ball.” When football is attempted, he wrote, “No rules are used to govern it except perhaps the first law of nature – self preservation” and “confusion reigns supreme.” He concluded, “Rouse, ye Seniors! Rouse, ye Sophomores! Let not that noble band of Freshmen, which is trying to introduce the game in its proper form, suffer defeat…Make a desperate attempt to introduce the most scientific, the most attractive, and the greatest of college games, foot ball.” On Oct. 30, 1893, St. Olaf lost to Shattuck Military Academy 14-6 in a game considered St. Olaf’s first “intercollegiate” game, but not many were to follow, then.

One reason football had a slow start was the growing national debate over the perceived “violent” and “brutal” nature of the game. In a lengthy Nov. 9, 1895, Northfield News article, Northfield citizens spoke out about “Foot ball As It is Played.” The newspaper’s opinion was that the game should be “rightly played” for amusement and exercise, “rather than going into it with fear and trembling and coming out scarred and stiff.” The rules should be modified to prevent “brute force” from reigning or “the game should be prohibited.” President J.W. Strong of Carleton praised the game for requiring “brain as well as muscle, quick thought as well as quick movement,” but condemned it when it turns into a “slugging match,” with the goal of “brute victory at any cost.” President Thorbjørn Mohn of St. Olaf said, “I have had enough of it. You can put me down for that…I am a thorough believer in outdoor sports and the game, if modified, would be excellent.. It seems awful to permit a game to be played at our colleges that endangers life and limb of students that are sent there to be educated and trained.” Margaret J. Evans of Carleton also suggested rule modification, while commending “many good features of the game” in developing “steadfastness, good soldiery, manhood, etc.” She admitted, “The greatest interest I take in the game is the learning of the news that Carleton is victorious.” Dr. H.L. Cruttenden said, “I think it is a genteel slugging match. I do not approve of the game as it is at present played, but as long as I am not the one to receive the aches and bruises, I will not complain.”

Max J. Exner, who taught physical education from 1892-98 at Carleton, is credited with instituting an athletic training program which improved the football program. In 1892, Exner wrote, “The man who wishes to play on the college team must live temperate and pure,” which means, “good nourishing food, good hard exercise, early hours and no stimulants.”

Training paid off, and in October of 1896, Carleton’s team basked in attention from the Minneapolis Times. The Times wrote: “The big Minnesota players were humiliated yesterday by the plucky little team from Carleton College by the score of 16-6.” It must be noted that this was a game Carleton lost in Minneapolis. In the next season of 1897, Carleton returned to play the University of Minnesota again and lost 48-6, but it was considered a moral victory to even score against the larger school. Carleton rooters, decked in “yards and yards of corn-colored ribbon” were reported to have “danced themselves dizzy” at the game after the lone score. A writer in Carletonia said, “Six in this case is a very big six.” In November, this team traveled to Grand Forks and defeated the University of North Dakota 20-0. The trustees provided money to hire coaches for 1898 and 1899, which also gave a boost to the program.

In 1894, the Carleton varsity had lost 12-6 to a Northfield High School team which had been formed just two years earlier. But Carleton usually prevailed against NHS, including a 53-0 win in 1903. The 1905 Carleton record of 6-0 included wins over NHS, Minneapolis East and Shattuck Academy. Games against high schools and prep schools ended in 1913. Football games had been sporadic at Carleton until 1897, when Carleton started playing between five and ten football games each fall except for war years.

The Carleton football team, which started playing on Laird Field in 1902, won the Minnesota Athletic Conference championship in 1905 and began an amazing winning streak. According to Carleton archivist, Eric Hillemann, the team’s record between 1905-1917 was 66 wins, 17 losses and 2 ties. In the years 1910-17, Carleton outscored opponents 1,520 points to 79. The team was undefeated from 1913-1916, under new coach C.J. Hunt. The team was not scored upon at all in the 1914 and 1915 season and the team of 1916 upset legendary coach Amos Alonzo Stagg’s University of Chicago team in Chicago by a score of 7-0. Hunt left Carleton in 1931 with a record of 75 wins, 22 losses and four ties. Laird Stadium, with seating for 10,000, was constructed in 1927, during his tenure.

Across the Cannon River, a gym in the newly constructed Ytterboe Hall had stirred up interest in athletics at St. Olaf and an Athletic Union was formed in the fall of 1900. But football was strictly an interclass affair and annual petitions for intercollegiate football were denied. In 1904, a cartoon in the Viking yearbook showed a football player, petition in hand, being rejected once again. The game was still considered to be dangerous and, indeed, 18 players were reported to have died in 1905, with 159 seriously injured. As described in “The Greatest Game: Football at St. Olaf College 1893-2003” by Tom Porter and Bob Phelps, President Theodore Roosevelt spurred meetings of representatives of universities in December of 1905 to “form sound requirements for intercollegiate athletics, particularly football,” which led to the NCAA. The resulting rules helped make football safer and more respectable, but it would be another 13 years before St. Olaf joined the intercollegiate football fray in 1918. But they found themselves playing with, not against, their cross-town rival, Carleton.

In December’s “Historic Happenings” column: St. Olaf and Carleton join football forces in 1918, then get each other’s goat; A St. Olaf face mask gains (Hall of) fame. Thanks to Eric Hillemann of the Carleton Archives, Jeff Sauve of the St. Olaf Archives, and athletic coaches Tom Porter, Bob Sullivan and Jim Dimick for assistance with this story.

Local Football Goatrophy Related to Slab of Bacon Trophy

A little-known connection exists between the trophy of a goat, which is fought over by Carleton and St. Olaf in football, and a trophy of long-time rivals (since 1890), the University of Minnesota and the University of Wisconsin. A goat resembling a saw-horse had been awarded for basketball superiority between Carleton and St. Olaf since 1913. A short article entitled “Local Colleges Seek Custody of New Goat” in the Oct. 16, 1931, Northfield News announced that a “relative of the famous basketball goat” would rest in a trophy case for the winner of the Oct. 17th football game. The story said: “The new goat, which is carved from a wood plaque, has been stamped ‘official’ by the athletic departments of both colleges. It is the work of a Minneapolis man who designed the ‘bacon’ Minnesota and Wisconsin universities fight for on the gridiron each fall. The newcomer is getting a final coat of varnish to preserve its sad expression and its football pants. It will be displayed before the game at The Toggery, which is furnishing the pig-skin case in which to keep the trophy.” The Toggery was a men’s clothing store which may have paid for the trophy. St. Olaf won the first football “Goatrophy,” as it was called, by a score of 25-6 and the St. Olaf team captain accepted it at a student body meeting on Oct. 23.

A little-known connection exists between the trophy of a goat, which is fought over by Carleton and St. Olaf in football, and a trophy of long-time rivals (since 1890), the University of Minnesota and the University of Wisconsin. A goat resembling a saw-horse had been awarded for basketball superiority between Carleton and St. Olaf since 1913. A short article entitled “Local Colleges Seek Custody of New Goat” in the Oct. 16, 1931, Northfield News announced that a “relative of the famous basketball goat” would rest in a trophy case for the winner of the Oct. 17th football game. The story said: “The new goat, which is carved from a wood plaque, has been stamped ‘official’ by the athletic departments of both colleges. It is the work of a Minneapolis man who designed the ‘bacon’ Minnesota and Wisconsin universities fight for on the gridiron each fall. The newcomer is getting a final coat of varnish to preserve its sad expression and its football pants. It will be displayed before the game at The Toggery, which is furnishing the pig-skin case in which to keep the trophy.” The Toggery was a men’s clothing store which may have paid for the trophy. St. Olaf won the first football “Goatrophy,” as it was called, by a score of 25-6 and the St. Olaf team captain accepted it at a student body meeting on Oct. 23.

Although it has been rumored without substantiation over the years that a “St. Olaf carpenter” designed the football Goatrophy, I believe, based on the Northfield News story cited above, that this Goatrophy was created by Dr. R.B. Fouch of Minneapolis, whose name is given on several websites (including both universities) as the creator of the Slab of Bacon trophy in 1930.

The Slab of Bacon trophy was made of black walnut, with a football carved into it showing the letter W or M, depending on the viewing angle. Scores of the games were inked into the back of the trophy. The winner of the Badger-Golden Gopher contests between 1930-1943 “brought home the bacon.”

The bacon trophy disappeared sometime after a Minnesota victory in 1943 and was replaced by Paul Bunyan’s axe in 1948. In 1994, the missing trophy was discovered in a storage room at the Wisconsin Athletic Department during a renovation of the stadium. Strangely, someone had put the scores of games through 1970 on the back of the trophy. When the Slab of Bacon trophy was found, then-coach Barry Alvarez joked, “We took home the bacon, and kept it.” The trophy now resides in the University of Wisconsin football office at Camp Randall Stadium.

It is not known why or by whom Dr. R.B. Fouch of Minneapolis was approached to design the Goatrophy, a year after he designed the Slab of Bacon. The St. Olaf and Carleton archivists can find no connection of Dr. Fouch to either college.