Northfield could hardly have been more welcoming. It was front page news when the Northfield News announced on June 18, 1898, that “Miss Baker’s boarding school for nervous and backward children” on Chicago Avenue in Minneapolis was to be “removed to Northfield” to the “fine and commodious Wilcox property” at the head of 3rd Street. On July 16, the News spoke of Laura Baker’s preparations for the Sept. 1 opening of “the only private school of its kind in the Northwest,” concluding, “Miss Baker is to be congratulated in the selection she has made for its location.”

The name “Laura Baker” is still familiar to Northfielders 114 years later through the Laura Baker Services Association, which last month was honored as Business of the Year by the Chamber of Commerce. But just who was Laura Baker? And is it true that her spirit haunts the facility that bears her name?

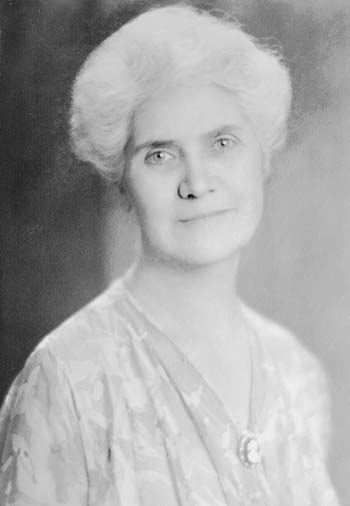

Laura Baker was born in Chariton, Iowa, on April 10, 1859. Maggie Lee wrote in the Northfield News of Jan. 28, 1994, “Miss Baker came from a family of activists, described by some as ‘liberal, open, even kind of wild-minded!’” Baker’s first teaching position was for seven years at the Glenwood Asylum for Feeble Minded Children in Iowa, followed by 12 years as principal at the Faribault State School for the Feeble Minded.

An account in the 1938 issue of Women’s Almanac (“a book of facts for, by and about women of distinction”) said that some parents of children at the state institution came to Baker with their concerns that their children were “too capable to be confined in a home for the feeble-minded, and yet not possessing sufficient ability to compete with average individuals in public schools and to progress in the usual manner.” Baker’s own observations had led her to believe that these children could be educated in a proper nurturing, yet challenging and progressive environment and, aided by parents, she started a boarding school in 1897 in Minneapolis. Searching for space in a more rural area, she moved her school to Northfield the following year to a large house with six acres on the eastern edge of town.

Baker lived with her students at 211 Oak Street during the first 19 years of the school, along with housekeepers, house mothers and teachers. The Northfield News of June 17, 1905, wrote approvingly of the “thorough work” being done there, as seen in an open house given by the private school: “Unbounded admiration and wonder was expressed at the skill and attainments of the pupils.” The article noted that individual training was given by four teachers from kindergarten to 8th grade in reading, spelling, writing, language, geography, arithmetic, physiology and history with special attention given to “articulation and the development of language.” Two evenings each week were said to be devoted to dancing, two to gymnastic activities, two to singing, with chapel on Sundays. The guests saw the children busily engaged in sewing, lace making and basketry (copying Indian and old colonial bead patterns). The students presented a program of dance, song and “winding of the May pole” for the guests. The story concluded, “Northfield is indeed fortunate in having such a school and every citizen takes pride in it.”

“Doing Splendid Work” was the headline of a June 25, 1920, Northfield News story about another program and exhibit of work at the school. “Miss Baker is the soul of the institution” but “modestly gives credit” to her teachers,” said the writer. Baker proudly announced she had been invited to commencement exercises at the University of Minnesota for a young man who had been a pupil for three years.

The Laura Baker School, with 35 students and seven teachers, was incorporated in 1919 in order to provide for its perpetuation. The school then faced a tax battle in 1920. The question was whether the school was entitled to be classified as an institution of learning and thus exempt from property taxes – or were the children merely taken care of in a custodial fashion? On Oct. 1, 1920, the Northfield News gave Judge A.B. Childress’ emphatic decision: “The work done and benefits accomplished by the ‘Baker School’ are of inestimable value to the state. Not alone in the matter of lightening our burdens of taxation, but this school lifts many children from a condition of darkness into light and from a condition little above the animal to that of cheerful, happy, human beings. In my judgment no greater benefit could be conferred upon the state.” The verdict: exempt from taxation.

The school was flourishing. Contributing to its success were activities such as dramatics, glee club, square, tap and ballroom dancing and band. (Baker’s philosophy was that singing, dancing and percussion would open minds to further learning.) In 1927 the Baker School bought a cottage at Roberds Lake that had been leased the year before from St. Mary’s school of Faribault. Each summer the school packed up for six to eight enjoyable weeks of swimming, boating, fishing, games and steak fries which continued into the 1980s.

Progress continued when plans were announced in August of 1928 to build a two-story brick dormitory (Margaret Graves Hall) on the campus to house between 18 and 20 pupils. Baker designed homelike living rooms with two-room suites sharing a bathroom, conditions unheard of in institutional multi-bed facilities. In September of 1928 the C.M. Buck mansion (to be called “Buckeye Hall”) in Faribault was purchased by Baker in association with Ruby Andregg, who would run the new school for 12 pupils.

By the end of 1937, the Laura Baker School had 50 students, 10 teachers, 8 house mothers and 12 other employees. The headline of the Northfield News of July 1, 1938, said it all: “Vision and Ability Mark Progress of Baker School; Laura Baker, Founder, Proves Educational Ideal With Notable Results.” By then a total of 350 pupils had enjoyed the “homelike atmosphere” and “advanced educational practices,” with the “sympathetic spirit of its founder permeating the entire institution.” (By the time of the 75th anniversary in in 1973, the estimate had doubled to 700 pupils who had been aided by the school.)

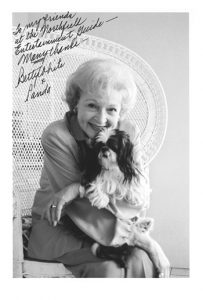

In her Jan. 28, 1994, story, Maggie Lee wrote of Laura Baker: “Miss Baker was a tall woman with regal carriage and, during many of her Northfield years, was crowned with snow-white hair. She was described as firm, desirous of perfection, yet patient and able to lavish love on her charges.” A student once gave her the nickname “Old Hawkeye,” a nod to her Iowa roots but, as Lee said, “also because she kept very close watch over her beloved charges.”

When Ruth Otis, a teacher at the school for 50 years, was starting out, she asked Baker apprehensively, “How will I teach these children?” Baker replied, “Just like you would a normal child. Of course – it will be a slower process, and you won’t always see results.” Otis said, “She was strict. I was sort of afraid of her when I first came. But she had a soft spot for the children – they came first always.”

In 1938, when Baker was 79 years old, Baker’s niece and namesake Laura Baker Millis moved to Northfield and began to take over the educational work at the school, with her husband Henry (Harry) Millis handling business management. Baker’s niece was a graduate of the National Kindergarten College of Evanston, Illinois, and quite prepared to continue her aunt’s work.

Laura Baker lived across the street from the Oak Street school and kept a keen interest in the school as she aged. She also reaped accolades for its long and continuing success. A parent wrote to Baker in 1941, “Since happiness comes from making others happy you should be the happiest person in the world. You stand ahead of anyone I have ever known for example of doing for others.” At the time of the 50th anniversary in 1947, when the school counted 53 residents, 9 teachers, 8 housemothers and 11 other employees, Baker was still active at age 87.

Toward the end, Baker looked back with satisfaction on her life’s work as she expressed her philosophy: “A pupil needs to wonder about a thing in order to learn about it. If one approach doesn’t bring a response, another must be tried to open up an interest. It is necessary to begin where the child is and to go on from there with the very next step.” She spoke of several children who were carried in by their parents and “have learned to run and dance,” others who were “unable to speak intelligibly” and “have learned to read out loud and sing” and still others who went on to be self-supporting. Three had even graduated from college. “I am happy,” said Baker.

Gary Gleason (who served as a director of Laura Baker Services) shared a story from his great-great-aunt Laura Baker’s later years with Ann Sherburne in Northfield Magazine of Winter 1989. Baker, feeling ill one day, called a nearby doctor to come over to her house. He asked questions about her health, then asked, “How old are you?” Baker replied, “Don’t you know how impolite it is to ask a woman her age, especially an older woman?” The doctor said, “If I were to give you any medicine, I would need to know your age to determine the correct dosage.” Baker finally told him she was 70 but swore him to secrecy. A month later the doctor read in the newspaper about festivities at her 90th birthday party.

Laura Baker’s final years were marked by frail health. When she reached her 100th birthday on April 10, 1959, the milestone was celebrated at the hospital with family members. She never married but “Auntie Laura” was beloved by nieces and nephews and their children. She reached her 101st birthday and died on June 7, 1960.

Northfield News columnist Nellie W. Phillips wrote a tribute to her friend on June 16, 1960: “One of the loveliest ladies I have ever known in my lifetime, Miss Laura Baker, passed away Tuesday, June 7, at her home after many years of suffering. I believe she had been in poor health about 15 years… One cannot mourn for one who has suffered so long, altho we will miss her so much. She has been an inspiration to many of us for years and years. She was such a beautiful woman and beautiful in character also. As she told me once, ‘I have never had children of my own but have been mother to many’…and she was in all respects.”

Phillips commended the care given Baker by her niece Laura Baker Millis and husband Harry and grandniece Laura Virginia (Millis) Gleason and husband Charles Read Gleason. A service was held at All Saints Episcopal Church, ending with a favorite hymn, “Now the Day is Over.” Phillips concluded, “Northfield can never be quite the same without our beloved Miss Baker.”

When the Laura Baker School reached its 75th anniversary, the Northfield News headline of Oct. 11, 1973, was “Laura Baker School Used Current Educational Practice 75 Years Ago.” The article noted, “In very recent years, interest and concern for the mentally retarded have grown greatly throughout the nation. But 70 years before this development, Miss Baker was carrying on a vigorous, forward-looking program, stressing health, education and training for retarded students in the school that bears her name.”

In 1975 the Education for All Handicapped Children Act provided for free, appropriate public education for all disabled children. When Gov. Rudy Perpich presided over the 1978 dedication of LBSA campus as a National Historic Place, he credited Laura Baker with helping to plant the idea that the developmentally disabled are “entitled to privacy, to dignity, and respect.”

Today the Laura Baker Services Association, which became a non-profit organization in 1979, has a myriad of services for people with developmental disabilities and their families. The school, which gives instruction for ages 5-22, is open to residents and non-residents alike. Supportive services are available for clients of all ages who reside not only at the Oak Street location but in five group homes and private homes as well. Epic Enterprise, a developmental achievement center in Dundas which opened in 1976, assists clients to attain independent living skills and provides daytime activities.

Laura Baker, who started her school in Northfield with just two other teachers assisting her, would be amazed that LBSA now has 146 full-time employees, with a $2.9 million payroll annually. In addition, LBSA has had a $10.44 million economic impact on the community, with a 19 percent growth rate over the last five years.

And what of the ghost that is said to haunt the Laura Baker site? The original house was razed in 1989 and replaced by a new administration building in 1990 but Delcie St. Hilaire, who has worked at LBSA since 1973, is certain she has heard Laura Baker’s footsteps in both locations. St. Hilaire says, “She used to wander from room to room in the original Laura Baker facility. I would hear doors opening and closing.” A video at the LBSA website even purports to show a ghostly figure on the staircase (which was preserved from the original house and installed in the lobby of the administration building). It’s even been said that furniture has been moved when the buildings are deserted. St. Hilaire says, “I just think she is still here checking up on how things are going.”

Fifty-two years after her death, Laura Baker’s spirit lives on in Northfield, perhaps as an apparition, but most definitely as a benevolent inspiration for the Laura Baker Services Organization.

Thanks to Laura Baker’s great-great-niece Laura Kay Allen and LBSA assistance from Jane Fenton, director of community relations; Sandi Gerdes, executive director; and Delcie St. Hilaire, human resources and payroll manager. To see the spirit on the staircase and for further information about the organization, go to laurabaker.org. A comprehensive history can be found here by an LBSA intern, Elizabeth Gray, written for her major at Carleton in 2008. Photos courtesy of Laura Baker Services Association.

Baker Promoted Respect for People with Developmental Disabilities

The dictionary says “moron is the highest classification of mental deficiency, above ‘imbecile’ and ‘idiot.’ Loosely, a very foolish or stupid person.”

No doubt you have heard those terms thrown around today and even used them yourself (“Oh, you’re such an idiot!”). The original name of the Laura Baker School at 211 Oak Street was “Miss Baker’s School for Nervous and Backward Children,” which may strike us today as insensitive. But other terms in common use at that time would sound worse: feebleminded, morons, idiots. In fact, when the Baker School tax case was heard in district court in 1920, a doctor testified that the children at the school “were found to be evenly divided in the classes known as morons and imbeciles.” Other words that have been applied include mentally deficient and retarded. Sandi Gerdes, executive director of the Laura Baker Services Association (LBSA), says, “We use people-first language: people with developmental disabilities. Once we have established the population that we support, we refer to the people or the person.”

Laura Baker’s choice to teach her pupils in a homelike environment, starting in 1897, was counter to the practice of warehousing of the developmentally disabled in state-run asylums where they were often subject to abuse and neglect and considered uneducable. In the early 1900s eugenic sterilization laws were effected by many states for “confirmed idiots, imbeciles and rapists.” But Baker had “respect for the dignity of human beings, whether they were old or young, wealthy or needy, male or female, regardless of their ability level,” Gary Gleason said of his great-great-aunt Laura in 1989. The mission statement of LBSA is “to respect the values, life choices and dreams of people with developmental disabilities and help them reach their goals.” As Gerdes said in a speech to the AAUW, “This humanistic and personal look at the individual has pervaded the LBSA culture over the years and made us unique…Everything starts with understanding this is a person.”