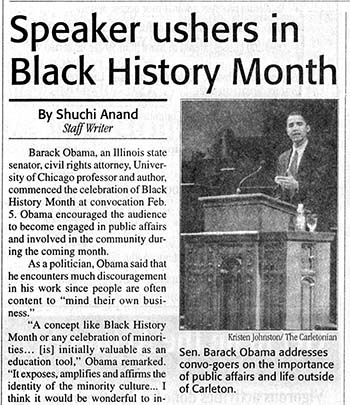

“Speaker Ushers in Black History Month.” So read the headline of The Carletonian of Feb. 12, 1999. A picture with the story shows Barack Obama at the pulpit of Skinner Memorial Chapel during a convocation held Feb. 5. Fortunately, a recording of his talk has been preserved.

“Speaker Ushers in Black History Month.” So read the headline of The Carletonian of Feb. 12, 1999. A picture with the story shows Barack Obama at the pulpit of Skinner Memorial Chapel during a convocation held Feb. 5. Fortunately, a recording of his talk has been preserved.

Obama was introduced as a “civil rights attorney, author, lecturer, community development specialist and the first African-American president of the Harvard Law Review.” Among his accomplishments: a B.A. in political science from Columbia University, community organizer in Harlem and in Chicago, magna cum laude graduate of Harvard Law School, a civil rights professor at the University of Chicago and Illinois state senator.

Obama began his speech by apologizing for “some sniffles that I’ve got.” He explained, “I am blessed with a 7-month-old daughter and those of you who are parents know that as cute as these babies are, they are actually germ-carriers and apparently I’ve got about five to six years of sniffles and colds to look forward to.” The audience laughed.

Obama said he almost cancelled his first-ever trip to Minnesota when the Vikings lost the NFC championship game the month before to Atlanta in overtime: “They broke my heart, but I assume they’ll do better next year.”

Obama announced the topic of his speech as “Politics and Public Life” and noted that when he first ran for public office, the people he talked to typically had two questions for him. The first was, “Where did you get this funny name of yours – Barack Obama?” Obama said that they “did not necessarily say it correctly” and the convocation audience laughed as he gave examples of variations of his name that he would hear: “Yo Mama” or “La Bamba” or “Alabama.” He explained that he got his name from his African father and his accent from his mother from Kansas.

The second question he would be asked was, “You seem like a nice young man. You’re clean-cut. You seem like you’re concerned about people and issues of the day. Why would you want to go into something nasty like politics?” Obama said that when he went into community organizing right after college, people also wanted to know why he would go into a low-paying job where “nobody appreciates you anyway.”

Obama said that “public life of any sort, politics, community activism, organizing, is not held in very high esteem in our culture these days…We assume the worst in our politicians and all too often they give us good reason for assuming the worst.” Politics seems to be “about self-aggrandizement and big business and moneyed interests and narrow concerns” and so people conclude that “we’re better off withdrawing into our own private careers, tending our own private garden.”

Obama told the convocation audience, “The measure of our greatness as a nation is not simply how big our GNP is or how many millionaires we are producing or how well the stock market is doing, but also how well we’re treating the most vulnerable in our society, the aged, or the children, or the infirm.” Citing Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s words, “Injustice anywhere is injustice everywhere,” Obama said, “We’re all connected somehow.” Although “we are in the greatest economic boom in our history,” Obama pointed out that “close to a third of children are living in poverty in big cities in America, an astounding statistic,” and families have to work two jobs. The stock market is going up “at the same time as trust and civility in our society are going down.”

Obama confessed that he did not have all the answers because, “After all, I’ve only been in public life and public office now for two to three years.” He joked, “When you invite me back in five years, maybe I’ll have all the answers then.”

What Obama did have, he said, are some principles to offer some hope and guidance that have given him some sense of direction and bearing. The first principle is taken from the civil rights movement. Dr. King, said Obama, had to “agonize over issues of strategy and issues of tactics” and “dissension and fear and betrayal had to be overcome in every single step in that long march towards freedom…The risks were great and the likelihood of failure was daunting.” Yet they kept going. Even in the midst of confusion and uncertainty, said Obama, it is important “not to be paralyzed by analysis” and to act on “what we think is morally right and morally just.”

The second principle is “the principle of public engagement.” Obama said, “We live in a privatized age” where television and shopping are “our main entertainments as opposed to conversation and community activity.” So we forget that we are social beings who are “significant in relationship to others.” Change takes place in America only through “the participation of ordinary people.” For example, Obama said, “Without Rosa Parks, there is no Dr. King,” and without people walking instead of taking the bus, “there is no Montgomery bus boycott.” Problems such as drugs and violence can be solved when “people are willing to work together at the grass roots level.” And you should get involved not out of guilt but because “you have an obligation to yourself” and “your individual salvation is tied to a collective salvation.”

Principle number three is an “insistence on empathy, a politics that is based on the belief that we share some common ground.” On campuses, said Obama, black students, Latino students and whites seem to emphasize their differences so that the “notion of common hopes, common dreams seems naïve.” While it is easier to stay in our own neighborhoods, “without empathy, without the willingness to step in somebody else’s shoes and see how it feels, it strikes me that we can never unleash not only the potential of this country but our individual potential.” If people sit down to talk and learn from each other, Obama said, then “diversity is the engine of excellence.”

Obama referenced both Dr. King’s speech at the Lincoln Memorial where Dr. King said it was not just a black thing but a human thing, so everyone can understand, and the founding fathers who said that all men are created equal with common values. These values, said Obama, include “honesty, kindness, hard work, discipline” and are not “African-American values or white values or Korean values, those are human values.” We must “take the initial leap of faith to say we do share come common hopes, some common dreams, some common values.”

The last principle, which Obama said was perhaps the most important, is the principle of hope. Hope is needed to “get out of your own private life and to engage publicly.” The most important legacy of every movement is “the belief that there are better days ahead,” but it should not be blind optimism, sticking one’s head in the sand like an ostrich, ignoring problems such as race and poverty. Obama said, to him, hope means “the hope of slaves sitting around a fire singing freedom songs, or the hope of immigrants landing in Ellis Island, not sure of what the future will bring…,” and hope in the midst of the difficulty and uncertainty of everyday life.

“You know, there’s something audacious about hope,” Obama concluded. “And in the end, I think that’s what I take away from Dr. King’s life, that’s what I take away from the other genuine, moral leaders of our country in the past. Their faith strengthens my faith. Their prayers and fears and doubts give me the courage to believe that, despite my weaknesses, I can be a better person. That despite all our differences, we can live together as one people. That despite the sordid history of this nation, we can unite as one nation. That we can feed the hungry, we can clothe the naked, and house the homeless and teach our children and employ the jobless and reclaim our streets from despair and violence. I believe those things. I believe we have a righteous wind at our back, that God is calling us to action, that our individual salvation is tied up with our collective salvation and that if we do what we must do, that if we reengage ourselves and recommit ourselves to public life, if we insist on shared values, if we insist on the things that bind us together, that our hope will be rewarded and our prayers will be answered and out of the darkness, a brighter day will come.”

Thanks to Eric Hillemann of the Carleton Archives for the story idea and the Carletonian account and CD of Obama’s 1999 speech at Carleton. And my gratitude to Josh Startup for his recollections of the speech and commentary on Obama, then and now.

Carleton Grad Recalls Obama Visit

Josh Startup (a 1999 Carleton graduate from Oberlin, Ohio) was a resident assistant and member of the department of residential life diversity committee at the time of Obama’s speech. Startup wrote in an email, “Having been impressed by his speech I snagged a seat next to him for lunch. I was a senior and headed out to DC to try and get involved in politics myself, and so we chatted about politics and oddly enough how to effect change. He emphasized it was up to young people like us to become involved, etc.” Josh said he remembered thinking to himself, “Why the heck is this guy wasting his time in the Illinois State Senate when he could be a U.S. senator?” and afterwards he told several people that Obama would be president one day (“though I didn’t realize it would/could be so soon”).

Obama gave Startup his card and told him to look him up if he ever wanted to work for him in Illinois. In the summer of 2007, Startup, now an attorney in Washington, D.C., ran into Obama while working out at a gym near the Capitol. They spoke briefly about his Carleton visit. Said Startup: “It was probably the low point in his campaign when Sen. [Hillary] Clinton seemed to have it already locked up.”

After refreshing his memory of the 1999 speech, Startup wrote in an email: “I think at the time of the speech the thing that connected with me most was when he spoke of being part of something bigger than yourself. That’s something that I’ve to a greater or lesser extent carried with me since Carleton. I can’t say he’s the first person I heard it from (I think my mother also used that phrase), but I recall being able to relate to that when he spoke of it, under his Principle of Public Engagement. I think I also agreed with him regarding the notion of common values, when he noted that certain values weren’t African American or white or Korean values but human values.”

Startup concluded: “What strikes me reading his speech now is how consistent his themes have been over the nearly ten years since he gave that speech. He touched on some similar ones in ‘Dreams for my Father,’ which was written before this talk, but was still five years before even his 2004 Democratic National Convention speech. It is clear from the talk that ‘Hope’ and ‘Change’ were not just invented for the Presidential run.”