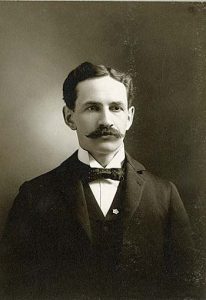

Although individual instruction in art was present from the early years of Carleton (which was founded in 1866), there was no art department until after World War I. In 1920, a Scottish gentleman, Ian B. Stoughton Holbourn, came to Carleton as “Professor of Aesthetics and Civic Art.” A survivor of the sinking of the Lusitania in 1915, Holbourn is described as “picturesque” in Headley and Jarchow’s book, “Carleton: The First Century.”

“On the campus, his flapping blue cape and his free-flowing artist’s tie, his evangelical enthusiasm for all things Hellenic, and his quick disdain for all things American made their impression on provincial Carleton. There were persistent rumors that he was king of a small, uninhabited island realm off Scotland and owner of a castle near Edinburgh.”

“On the campus, his flapping blue cape and his free-flowing artist’s tie, his evangelical enthusiasm for all things Hellenic, and his quick disdain for all things American made their impression on provincial Carleton. There were persistent rumors that he was king of a small, uninhabited island realm off Scotland and owner of a castle near Edinburgh.”

These “persistent rumors” were true, although the island he had bought, Foula, was not uninhabited (there were more than 150 subjects in his time, although only 30 today). The castle he owned and was restoring was called Penkaeth Castle.

From 1920 until his death in 1935, Holbourn ignited a passion for art on campus, although he usually worked but one semester a year due to his lecture commitments. According to one source, “Starting with nothing, Carleton soon became the college with the largest percentage of students taking art courses in any college or university in the world.” This was accomplished with such a limited budget that Carleton’s president Donald J. Cowling said, “All this Professor Holbourn has done not only without straw but without bricks.” The American Board of Education selected Carleton and Swarthmore as two of the best and most progressive colleges in the United States. Students praised him for making them think, because he would tell them, “I do not mind if you contradict me and prove me wrong; what I do not want is my own lecture dished up again.” Quotes from his lectures appeared on postcards, with such sayings as, “Never be satisfied with what can be done – any fool can do that. Strive to do the thing that can’t be done.”

From the beginning, Holbourn was anxious to get the art department “properly on its feet,” offering to give six lectures for his $100 per lecture fee to raise money for the department. Money was often a concern in correspondence found at the Carleton Archives. In January of 1921, he wrote to President Cowling that he was looking forward to his return to Carleton, but he wished university work could be “better paid.” That it was not was “a serious reproach to civilization.” He added, “I very much prefer working at Carleton to making money – of course, I should not otherwise have accepted the position.” By June of this same year, Holbourn was complaining that the number of students he was teaching (163) was “too many for one man.” Yet, he said he was “delighted with Carleton. The atmosphere seems to me the best of any educational institution of college or university standing that I have seen in the country.” In 1924, Holbourn wished to add courses to the art department, but President Cowling (while praising his “splendid results”) said it could not be done, due to “sharp financial limitations,” which became a constant theme over the years.

Holbourn was a native of Yorkshire and a graduate of the Slade School of Art at the University of London and Merton College, Oxford University. He gained renown traveling widely as a staff lecturer for the Oxford and Cambridge extension programs. Described as the “Apostle of Beauty,” he brought to the world his message of the need for Greek inspiration and for the principles of beauty and design in life, aimed at showing the value of the past. His far-ranging topics included archeology, Greek philosophy, poetry, Medieval history, art and architecture, social and ethical problems. By 1928, Holbourn had completed a million miles of travel.

Holbourn had successful lecture tours in the United States during the years 1913-1915, giving about 1,000 lectures from coast to coast. For a return trip home, he booked passage on the Lusitania.

Holbourn knew the Lusitania would be sailing into the war zone, so he talked to the passengers about proper evacuation procedures. Holbourn said he was ordered to “stop talking about such things because he was upsetting the passengers.” When a German torpedo hit the Lusitania on May 7, 1915, Holbourn stuffed manuscripts into his lifebelt and jumped into the sea, becoming entangled in ropes. Freeing himself, he swam for a lifeboat, which was full. An account said, “Fearing that he and his manuscripts would be lost, he threw his manuscripts into the boat so at least his papers would be saved, and then grabbed onto a rope trailing from the stern of the lifeboat.” He was then dragged into another boat. He later wrote that seeing and hearing so many people drowning painted a picture “too ghastly to describe.” (1,198 of the 1,959 passengers perished.) Holbourn retrieved some of his papers, but said he lost years of research, slides and lecture notes.

While a student at Oxford in 1899, Holbourn was on an expedition to Iceland when his ship passed Foula, 50 miles off the northern coast of Scotland among the Shetland Islands. He became entranced by this island, filled with cliffs and peaks (the tallest of which, at 1,220 feet, is the second highest in Great Britain). He returned in 1900 to buy this five-mile square island, despite family disapproval of this “harebrained investment.” When not in their Edinburgh castle, the Holbourn family spent summers here, among the fishermen and farmers. Half a million birds called Foula home and brought some fame to the isolated island. (A year after Holbourn’s death, more fame came when “The Edge of the World” was filmed on Foula in 1936.)

Foula had been acquired by Scotland from Norway. According to a story in The Carletonian, “It was given as a pledge for the dowry of the Norwegian Princess Margaret who married King James III of Scotland. The dowry was never paid. Courts had found the island to be odal property; that is, the British government had no jurisdiction over it. For all intents and purposes Holbourn was king of the island.” In a 1933 St. Paul Daily News Magazine story about Carleton’s “king,” Holbourn said, “It’s the loneliest island you can imagine, yet I enjoy it because no other spot can give me at sense of the power and force of nature as can Foula. You ought to be there when the hurricanes rage – your cyclones and tornadoes are lulling breezes in comparison.”

In the summer of 1935, Holbourn was making plans to return to Carleton from Scotland. In one of his last letters to President Cowling, Holbourn noted salary reductions and wrote, “I suppose we are all, Carleton included, like the eels – getting used to getting skinned.” He was still hoping for more staff and equipment for the art department, but (in a letter not sent in the wake of his death), President Cowling said there was no hope of expansion.

In Holbourn’s last letter, dated Aug. 26, 1935, Holbourn spoke of being in a “sort of dizzy stupor” due to “over-strain” and “some kind of poison in the system.” He wrote of a “horrible operation” to come and added, “Apologies for this awful letter” at the top.

Holbourn died in Edinburgh on Sept. 14, 1935, at the age of 62, just a couple weeks after surgery. The day before he left for the hospital, he had told his wife, Marion, that he had made an “epoch-making discovery” in his philosophy and hoped to write about it.

A faculty statement on Oct. 2 noted that Carleton had lost “a loyal and devoted friend” who was loved and admired by his students for his “stimulating personality in the classroom, his varied enthusiasms and the kindly but subtle humor of his criticisms of student life.”

Holbourn’s influence on Carleton lived on decades after his death because, in 1923, Holbourn had recruited Alfred J. Hyslop from Scotland for Carleton. (“A capable sort of fellow,” wrote Holbourn at the time.) Hyslop succeeded him as department chairman and eventually was able to expand the department. Hyslop taught at Carleton until 1963, presiding over the construction of the Boliou Memorial Art Building in 1949.

Among Holbourn’s publications were books and articles on art and architecture, a novel and poetry. His wife compiled “The Isle of Foula” from his manuscripts and published it in 1938. But Holbourn had much unpublished writing. In 1970, one of Holbourn’s sons wrote to Carleton to say that his father had left behind between 200 and 300 pounds of unpublished lecture notes, on many topics. Carleton’s archivist, Eric Hillemann, estimates that maybe five pounds can be found filed in the Carleton Archives today.

Shortly after Holbourn’s death, his wife, Marion, wrote to President Cowling, “His great regret (and almost his last words) was that his life work was unfinished. Of course it was unfinished and would always be so, because his vision and aim was Infinity. It is indeed only now really beginning.”

Thanks to Eric Hilleman of the Carleton Archives.

Professor Holbourn Speaks on the Neglect of Art and Beauty:

If we take the average of society we can divide it into two classes. The one class can be described as inclining to ignorance; the other as inclining toward indifference. And it is in the direction of ignorance and indifference that we are to seek for the source of our trouble. We say there is a hunger for beauty. But is there really?…We go into a shop to purchase for instance a coal-scuttle, a candlestick or whatever it may be and the shopman produces an article stamped with a vulgar machine-made design. We know it is bad but we shrug our shoulders and say to ourselves “Oh, I suppose it will do.” But that is not the way we should do. We ought to turn to the shopman and say, “How dare you show me anything like that. Take that abomination away and never venture to show either myself or any other customer anything so horrible.” You would find it would produce quite an impression on the local tradesmen if everyone of you in the future talked to them like that…Personally I have been going without things for many years on this principle.