Carleton College archivist Eric Hillemann has a colorful poster from the 1930s on his office wall which announces a lecture: “James B. Pond presents Admiral Byrd’s Second-in-Command Larry Gould (Dr. Laurence M. Gould) who will tell the thrilling story of the Byrd Expedition,” including motion pictures and “glorious color slides.”

It was just such a lecture (given more than 60 times in 17 states between October of 1930 and May of 1931) which brought Gould to Northfield for the first time to Skinner Memorial Chapel on Oct. 14, 1930. A spell-binding speaker and noted geologist, Gould had just returned that summer from a 1928-1930 expedition to Antarctica with famed explorer Admiral Richard E. Byrd. Two years later this genuine “rock star” of his era was hired to be head (and only member) of the new Geology and Geography Department at Carleton College. Gould went on to become a legendary president of the college from 1945 to 1962, building its reputation as one of the top liberal arts schools in the nation.

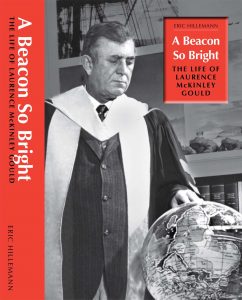

At the time of Gould’s death in 1995, Hillemann put together an exhibit on Gould at the library (where the Carleton Archives are housed). Stephen R. Lewis Jr., who was president of the college from 1987 to 2002, suggested that Hillemann should write a biography of Gould. Hillemann started researching the book in 1998 and worked on it off and on for 14 years. In mid-December, Hillemann’s book will at long last be published by Carleton College with the title, A Beacon So Bright: The Life of Laurence McKinley Gould.

Current Carleton College president, Steven G. Poskanzer, writes in the introduction that stories about Carleton’s fourth president “remain legion” and “Therefore, it is most fortunate that Eric Hillemann has taken on the very considerable task of capturing Gould’s family background, personal history, scientific achievements, and academic leadership in this detailed and thoughtful book.”

Gould (born on Aug. 22, 1896) grew up on a farm near the village of Lacota, Michigan. He showed academic promise and speaking prowess from the start as salutatorian of his South Haven High School class of 41 students in 1914. He gave a commencement speech in which he said the world demands educated men and women, “filled with enthusiasm.” Ambition, which he called “the mainspring of life,” must be “combined with industry, as we cannot dawdle through life.”

Gould followed his own advice, teaching grades 1-8 in a one-room schoolhouse in Boca Raton, Florida, to be able to afford entrance into the Univ. of Michigan at Ann Arbor, a goal he achieved in the fall of 1916. He had aspirations to become a lawyer like his personal hero, Abraham Lincoln. Gould roomed at the home of Professor William H. Hobbs, head of geology.

After a stint in Europe with the Army Ambulance Service during World War I, Gould returned in the fall of 1919 as a 23-year-old sophomore. Inspired by an introductory geology course from his former landlord, Gould went on to earn bachelor’s, master’s and doctor of science degrees in the field at the Univ. of Michigan and to teach there. He also met his future wife, Peg Rice, when she took a class from the popular young geology teacher.

In the summer of 1926, Gould accompanied his mentor Hobbs on a Univ. of Michigan glacial studies sailing expedition to Greenland as second-in-command. As Hillemann writes, this summer “marked only the beginning of a lifetime’s fascination with the ends of the Earth.” In the course of this first expedition, Hobbs named a lake for Gould. The next summer, Gould took part as assistant director and geographer in a Baffin Island Expedition in the Canadian Arctic to map uncharted territory, sponsored by the American Geographic Society.

Richard E. Byrd, an explorer already famed for his flight over the North Pole in 1926, was in the process of planning an expedition to the South Pole, backed in part by the New York Times, a trip combining science and aviation. Gould made his interest known and was selected as geographer and geologist. Hillemann writes: “In the end, when it was ready to leave the United States, the Byrd Antarctic Expedition consisted of 82 men, and more than 500 tons of supplies and material, including four airplanes, ready to be shipped to New Zealand aboard four ships.” He notes that the New York Times sent along a reporter, made photographic studio portraits of each member and, “with less fanfare,” also prepared prewritten obituaries.

On Dec. 26, 1928, Byrd wrote, “Gould I have made Second in Command. A splendid fellow, competent, a brilliant geologist, and popular with men.” A permanent base with barracks and workrooms called Little America was established on Antarctica’s Ross Ice Shelf with only radio contact with the outside world.

In March of 1929, the news radioed back to the States from the New York Times reporter was ominous. Gould, aviator Brent Balchen and radio operator/backup pilot Harold June had flown 135 miles east of the base to examine exposed bare rock in a mountain range named for one of the trip’s backers, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., and there had been no communication with them for three days. A fierce gust of wind in a blizzard had wrecked their plane, necessitating a dramatic airplane rescue operation from the base. Gould would later protest that his initials, LMG, did not stand for “Lost in Mountains Gould.” Gould said, “We knew where we were.”

From April 19 to late August, the expedition spent a long, sunless, “groundhog-type” winter at Little America before resuming research. Then, on Nov. 4, 1929, Gould and five other men set out with sledges pulled by 46 dogs to provide ground support for Byrd’s projected flight over the South Pole (the historic flight took place on Nov. 28-29). They were also to conduct a scientific investigation of the Queen Maud Mountains named by Norwegian explorer Raold Amundsen in 1912 during his party’s trek to the South Pole. Gould, the first geologist in Antarctica, would make assessments of the interior during a trip which would take two and a half months (until Jan. 19, 1930) and cover more than 1500 miles of icy, crevasse-filled terrain.

After his ascent of Mt. Nansen, Gould sent an eloquent radiogram to Commander Byrd back at the base: “No symphony I have ever heard, no work of art before which I have stood in awe ever gave me quite the thrill that I had when I reached out after that strenuous climb and picked up a piece of rock to find it sandstone. It was just the rock I had come all the way to the Antarctic to find.” In his 1931 book Cold: The Record of an Antarctic Sledge Journey, Gould wrote that finding sandstone “repaid me for the whole trip,” by showing that these mountains were part of “the most stupendous fault block mountain system in all the world.” The discovery of low grade coal was also an evidence that Antarctica once had a more temperate climate.

Another dramatic discovery was of a cairn of rocks left by the Amundsen party. A tin can was found with a note in Norwegian dated Jan. 6-7, 1912, confirming the party had reached the South Pole in December of 1911. (Gould kept the note and presented it to the Norwegian Geographical Society in January of 1949. King Haakon of Norway bestowed on him the Cross of St. Olaf, making him a Knight of the Royal Order of St. Olaf. Gould later noted that with this medal his “standing among Norwegians here in Minnesota has risen very greatly.” On display at the Carleton library is the Quaker Oats can itself, along with a cairn of glacial boulders from Carleton’s property made by sculptor Ray Jacobson in Gould’s honor in 2002. Among the items Gould left behind was a rock hammer which was found in 1962 by glaciologist Charles Swithinbank’s expedition and returned to Gould with a note which read, “Here is the hammer you left at Mount Betty some time ago. I hope that its absence has not caused any great inconvenience during the intervening years.”)

Gould’s party then continued east, passing the 150th Meridian, claiming this new hitherto unseen territory for the United States. Hillemann marveled to me about their experience: “In all of human history, these mountains have never been beheld by human beings before. The exquisiteness of that feeling must be such compensation for the hardships that you go through to get there.” And while they did go through a lot, the Byrd expedition returned without losing a man (unlike that of English explorer Robert Scott, whose party reached the South Pole five weeks after Amundsen on Jan. 17, 1912, and perished in March on the return trip). Byrd called Gould’s sledge trip “the outstanding personal achievement of the expedition.”

Hillemann told me that the Byrd Antarctic adventure was “like the moon landing of its day” and, thanks to newspaper accounts and banner headlines throughout the expedition, “Gould came back a national celebrity.” A ticker tape parade awaited the returning heroes on June 19, 1930, in New York, with a City Hall ceremony before 50,000 people. They were also welcomed by President Hoover in Washington, D.C. Then, back in Michigan on Aug. 2, Gould married his fiancée Peg Rice. The newlyweds lived in NYC for two years as Gould worked on post-Antarctic projects and lectured throughout the country.

Hillemann writes that Donald J. Cowling (who had been president since 1909) had “established for Carleton the opportunity for greatness” and, with the hiring of Gould in 1932, the college attained greatness by capitalizing on Gould’s “rich gifts of personality, leadership and character.” From the start, the college was enthralled by this celebrity in their midst. The students, then numbering around 800, filled Skinner Memorial Chapel to listen raptly to a talk by Gould that fall. As for Gould, he wrote to a friend that one of his first impressions was of “the superior quality of the student body compared with what I had known at Michigan.” (Hillemann also notes that, at the time of Gould’s arrival, 44 people or one out of every 94 Northfield residents were listed in Who’s Who, when the nationwide ratio was one in every 3,910.)

Hillemann gives abundant testimony from Carleton students of the 1930s and early 1940s about the “exceptional quality” of Gould’s teaching, his extraordinary qualities of humor, wit, eloquence and “ability to make his subject mesmerizing.” Gould was also noted for the sartorial splendor of his neckwear. In November of 1933, the first of many successive “Wild Tie Days” was held at Carleton in Gould’s honor, with the predominant color being Gould’s favorite – red.

In the spring of 1934, Gould gave a chapel talk to seniors which included the words, “You will always be members of this college and will always be expected to have a deep appreciation of the necessity of schools and colleges such as this – for these are the very agencies which civilization has created to conserve and perpetuate the ideals of freedom which seem so precious.” During speeches later throughout his presidency, Gould would use some variation of “You are forever a part of Carleton and Carleton is forever a part of you,” a thought that has been echoed by subsequent presidents of the college.

During World War II, Gould headed up the Arctic, Desert and Tropic Information Center of the Air Force in Minneapolis and then in Manhattan, which necessitated a leave of absence of three semesters. He returned in the fall of 1944 and on May 12, 1945, was offered the presidency of the college, producing great elation on campus. The victory bell was rung at Willis Hall and the next day the student body dressed in bright red.

Hillemann told me that one of the surprising things he learned from Carleton archive records was about that presidential search: “In our institutional memory now of Carleton College, Larry Gould is the legendary iconic figure….I was on the edge of my seat – are they going to hire him or not? Even though I know how it comes out. They were so reluctant to hire someone from the faculty. It’s generally not a good idea except under exceptional circumstances. In hindsight: These are exceptional circumstances! Hire him! It’s going to be wonderful!”

And it was wonderful.

In part two of this story in the Entertainment Guide of January 2013, Gould’s presidency from 1945 to 1962 brings unprecedented prestige and publicity to Carleton College. Gould goes on to have a long, productive life in sunny Arizona and, by the time of his death at the age of 98 in 1995, has made a total of seven trips to the icy Antarctic. And he makes a very memorable last trip back to Northfield.

Thanks to Eric Hillemann for his customary cooperation with my stories. A native of Madison, Wisconsin, Hillemann has been archivist at Carleton College since 1990. He earned an undergraduate degree from Brown University and has master’s degrees in American history and in library and information science from the Univ. of Wisconsin. A Beacon So Bright will be available at Carleton’s bookstore Dec. 15 and can be ordered before and after that date at carleton.bncollege.com.