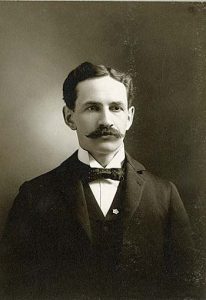

John North

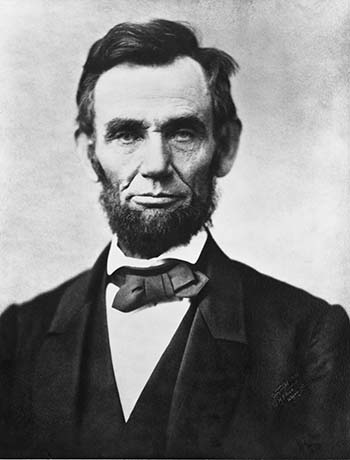

President Abraham Lincoln never set foot in Northfield. Nevertheless, as the nation celebrates the 200th birthday of Lincoln on Feb. 12, Northfield can claim a special tie to one of our most revered presidents through the town’s founder, John North.

North, a native of New York, was an ardent abolitionist. He engaged in anti-slavery debates and attended the first state abolition convention in 1835 at Utica.While attending Wesleyan University in Connecticut, he became an agent of the Connecticut Anti-Slavery Society. In 1849, he moved to St. Anthony in Minnesota with his second wife, Ann Loomis North, and opened a law office there. In 1851, on Jan. 1, he became a member of the territorial legislature and in the very next month introduced a bill founding the University of Minnesota.

In 1855, the Minnesota Republicans organized in the parlor of the North home in St. Anthony, the same year that North developed the town site of Northfield and built two mills on the Cannon River. His family joined him in Northfield in 1856, and the next year he led the Republican wing of the Minnesota constitutional convention, arguing for suffrage for both women and blacks.

So, it was no surprise that, in 1860, North was chairman of the Minnesota delegation to the Republican National Convention. In 1924, John North’s daughter Emma wrote a magazine story, “Memories of a Frontier Childhood.” In it, she portrayed herself as a “little calico-clad, pink sun-bonneted child of eight years,” and she recalled her father’s trip that spring to “some immensely important meeting in a far-away place called Chicago.” North’s “interests extended over a larger field than was circumscribed by his saw-mill and his gristmill on either side of the swift-flowing Cannon River,” and now he was a delegate to the “great Republican Convention,” said Emma. As a child, she was aware that politics of the time had to do with “affairs of the colored people” and Emma wrote that she always “caught somehow the trumpet note of championship” when her father discussed “this oppressed race.” A black minister had been a guest at their home and Emma also remembered rising to the occasion “as a true daughter an abolitionist” when a “little colored girl was brought to our school – offering at once to share my seat with her.”

North’s family in Northfield eagerly awaited the letters from Chicago. They learned that meetings were in an immense wooden building which Emma said “bore a name particularly attuned to my frontier ears – the ‘Wigwam,’ the very name of the Indian tents with which I was familiar.” Emma said that, after some difficulty selecting a candidate (it had come down to Seward and Lincoln, with Minnesota supporting Seward) and amid excitement and enthusiasm, word came that “they had come to agreement on some one called Abraham Lincoln.”

Another letter from North told the family that he had been sent by rail with others to Lincoln’s home in Springfield to “tell him the great news.” When North got back to Northfield, said Emma, he told the family of his visit to the “tall, grave, kindly man and his ‘lady’ in the plain home, and of the celebration through the town.”

North’s biographer, Merlin Stonehouse, in John Wesley North and the Reform Frontier (1965), wrote that the official delegation was received by Lincoln in his back parlor. Lincoln accepted the nomination, “shook each by the hand, and harked to each name, all with an attentive ease and grace that surprised some of them.” After supper, the delegates heard speeches at the state capitol, saw a fireworks display and boarded the train back to Chicago at midnight.

North campaigned in Illinois for Lincoln and after the election joined other office seekers in Springfield, asking to be appointed Superintendent of Indian Affairs. Lincoln was non-committal, but did invite North to join him and his wife on the train to Chicago to meet the vice presidential candidate Hannibal Hamlin and also invited North to the inauguration.

North’s financial situation was precarious, as a result of his costly promotion of a railroad, and North had to sell some railroad bonds just to buy new clothes for the inauguration. Stonehouse reported that the “weather cleared as Lincoln stood on the crude scaffolding to deliver his address, the clouds parted, and a star shone in daytime above his head,” which was given “mystical significance” by the crowd.

Hoping to press his case for an appointment, North wrote, “Things are in a whirl and I must grind out something in a week.” On March 7, North called on the president at the White House but, said Stonehouse, the Minnesota delega-tion was “not about to cut themselves off from lucrative patronage and perhaps graft by allowing the appointment of a man of North’s principles” to the post North desired. They hoped that North could be “made governor of a distant ter-ritory where his criticism and competition for local office would be removed from Minnesota.”

President Lincoln appointed North to be surveyor-general of the new territory of Nevada, which was to be cut off from Utah Territory. Emma, looking back on that time, was frightened to see how far away the area looked on a map, and North wrote the family that he “felt at first he could not think of it,” but after friends talked of the mining opportunities available there, North accepted.

President Lincoln appointed North to be surveyor-general of the new territory of Nevada, which was to be cut off from Utah Territory. Emma, looking back on that time, was frightened to see how far away the area looked on a map, and North wrote the family that he “felt at first he could not think of it,” but after friends talked of the mining opportunities available there, North accepted.

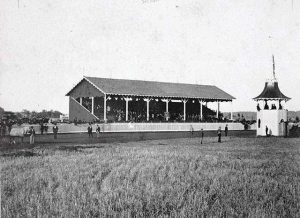

Emma wrote: “My mother, always courageous, faced the situation with the indomitable spirit which was continually an inspiration as well as a comfort and source of strength to my father.” Emma wrote touchingly of familiar spots in Northfield “growing dearer with the thought of leaving them,” such as the “substantial house of wood with its long piazza where we could play, and where the ever interesting stage-coach passed and re-passed daily.” She wrote of their pet fawn Jennie and giving away “our fine red and yellow sleds,” named Gypsy, Pony and Young American, “on which we had gaily dashed down the slow-clad hill-side all the winter past.”

In the midst of dismantling their household came word that Fort Sumter had been fired upon and President Lincoln called for first volunteer soldiers for the Civil War. Emma watched wagons pass by the door, filled with men who were friends and neighbors, all carrying flags.

Household goods were shipped around Cape Horn and John North and an aunt went ahead, arriving in Nevada on June 22, 1861. The rest of the family stayed for a year on a family farm in New York, North’s home state, then traveled by ship via Panama, California and by stage across the Sierra Nevada to Nevada territory.

North was the first federal officer on the scene and was admitted to practice at the Nevada bar but, he wrote his family, “we shall have to wait for law practice until after the legislature meets and gives us some laws.” Ever industrious, he planned the development of Washoe City, a sawmill and Minnesota Mill. Emma said social conditions were chaotic and the first legislature made corrective laws which quite commonly could not be enforced, with gambling, highway robbery and murder continuing to be rampant.

Emma wrote, “I think an engraved portrait of President Lincoln was the only picture on our walls, for, like my mother’s piano, the old engravings remained behind, in Minnesota.” In July of 1862, North’s federal surveyor position ended with consolidation of Nevada and California offices. Lincoln then named North to be an associate justice of the Supreme Court and judge of the District Court of Nevada Territory, based seven miles away in Virginia City. The stakes were high. “In response to judicial decisions,” wrote Emma, “stocks in San Francisco jumped or dropped. Men who had invested heavily grew wildly jubilant – or shot themselves.” In 1863, North was president of the constitutional convention in Nevada to prepare for statehood, just as he had been for Minnesota earlier.

It took a second convention and a push from Lincoln to bring about statehood. Lincoln was counting on Nevada’s vote as a state to support the 13th amendment abolishing slavery. Lincoln was quoted as saying, “It is easier to admit Nevada than to raise another million of soldiers” for his armies and “to fight no one knows how long.” The state of Nevada voted for the amendment.

An interesting side note is that John North knew the brothers Orion and Samuel Clemens during this time. Orion Clemens was secretary of the territory and lived in Carson City. Sam (“Mark Twain”) was city editor of “Territorial Enterprise” in Virginia City. Sam Clemens had accepted a challenge to a duel and North warned him that he would impose a two-year sentence on him if he did not get out of town. “He wouldn’t pardon us out to please anybody,” wrote Mark Twain in his book “Roughing It.”

One of their guests was the Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the State of Minnesota, who held the post North had hoped to get. Emma wrote that this was “an interesting meeting between this man who had had to face the subsequent Indian troubles of Minnesota [1862] and the man who had escaped them.” In 1864, while North served on the Nevada Territorial Supreme Court, a powerful attorney named William Stewart accused North of taking a bribe in a mining case. North pled his case to Lincoln, but resigned on Aug. 22, 1864, and in December instituted a defamation suit against Stewart and a newspaper that had backed Stewart’s claims. The Supreme Court referred the action to three referees in September of 1865 and North was found blameless. By this time, North’s position as a federal judge had ended with Nevada state-hood, he had sold his property and was preparing to move to Tennessee as a carpetbagger (he would later return to the west to found the towns of Riverside and Oleander, California, in 1870 and 1881 respectively).

In the spring of 1865, when the North family was living temporarily in Santa Clara, California, word came of an unimaginable tragedy. Emma recalled that, “In the midst of national rejoicing that the Rebellion was at last put down, I came in from school one day to find my mother lying upon a couch and sobbing. When she could speak, she told me that President Lincoln had been assassinated. The whole world seemed suddenly to turn dark.” Emma found a letter that Ann North had written to her parents, describing the reaction in this town, “since the dreadfulness of the assassination came,” where “Every house of loyal citizens is draped in mourning…all business has stood still…Strong men weep…Many so overcome with grief as to be obliged to take to their beds.”

Emma concluded her recollections with the words, “A band of crepe about my arm, grave and reverent, I walked in the sad little procession to the village church, no more the small sun-bonneted child who had perched on the zigzag fence five years before, but one who had come to see and feel and a little, perhaps, to understand something of that larger, broader world which had begun to be her own.”

John North returned to Minnesota in 1883, visiting Northfield and the University of Minnesota campus. He also made a last speech at a reunion of abolitionists in his native New York. John North died on Washington’s birthday on Feb. 22, 1890, and is buried in Riverside, California.

Thanks to Jeff Sauve of the St. Olaf Archives for finding the 1924 magazine article by John North’s daughter Emma North Messer and for providing links to the Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. A version of this story is also featured in the Northfield Historical Society’s Winter 2009 newsletter, “The Scriver Scribbler,” which is edited by Sauve, and is available at NHS and online at www.northfieldhistory.org. Photo of John North courtesy of NHS.