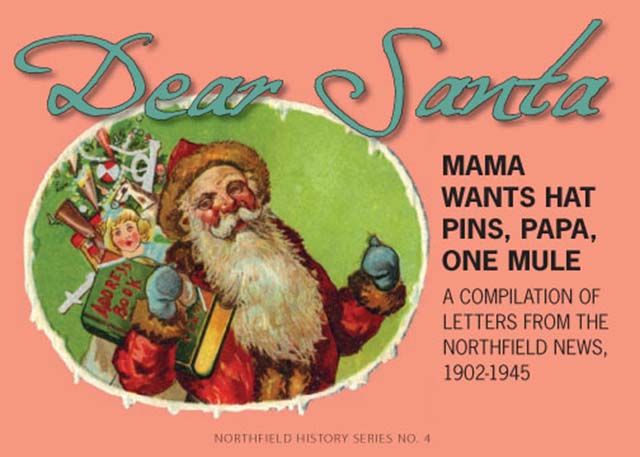

Need a suggestion for a stocking stuffer? Well, here it is: a compilation of kids’ letters to Santa from the Northfield News from 1902 to 1945. Dear Santa: Mama Wants Hat Pins, Papa, One Mule is a 5” x 7″ book published by the Northfield Historical Society Press last year as the fourth in the Northfield History Series. It can be enjoyed by all as a nostalgic, heartwarming, often amusing trip back in time to when youngsters wrote Santa in care of the newspaper with their Christmas wishes for such things as candy, nuts, dolls, overshoes and – oh yes, please don’t forget, Santa – a machine gun.

Jeff M. Sauve, Associate Archivist at St. Olaf College, told me that the inspiration for this book came from reading “Do You Remember?” by the Northfield News columnist Maggie Lee in 2004 about “Dear Santa” letters published in past issues of the News. Sauve clipped out one engaging letter by Harold Herkenratt of Dundas reprinted from 1908. Harold asked for a sled and a pony and reminded Santa of the cork gun he got one year: “I scared the cat with it and made him run behind the stove.” Sauve filed it away, “with no intention of a book,” but the idea came up for consideration years later after Sauve edited the first book in the Northfield History Series, Pioneer Women, Voices of Northfield’s Frontier, 1856-1876. This 2009 book was named best new publication by the Minnesota Alliance of Local History Museums. The series itself is a memorial to Barbara A. Will, who had been a member and president of the Northfield Historical Society board and active in service to her community.

Jeff M. Sauve, Associate Archivist at St. Olaf College, told me that the inspiration for this book came from reading “Do You Remember?” by the Northfield News columnist Maggie Lee in 2004 about “Dear Santa” letters published in past issues of the News. Sauve clipped out one engaging letter by Harold Herkenratt of Dundas reprinted from 1908. Harold asked for a sled and a pony and reminded Santa of the cork gun he got one year: “I scared the cat with it and made him run behind the stove.” Sauve filed it away, “with no intention of a book,” but the idea came up for consideration years later after Sauve edited the first book in the Northfield History Series, Pioneer Women, Voices of Northfield’s Frontier, 1856-1876. This 2009 book was named best new publication by the Minnesota Alliance of Local History Museums. The series itself is a memorial to Barbara A. Will, who had been a member and president of the Northfield Historical Society board and active in service to her community.

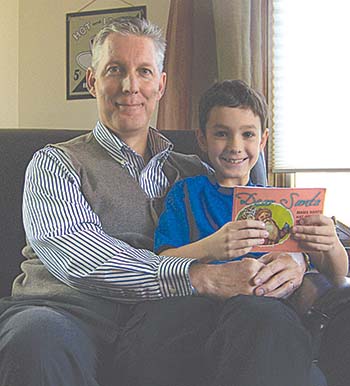

Sauve said that he thought a book of children’s letters to Santa could be “just playful and fun,” capturing “the children’s innocence,” while also looking at “how Christmas has been part of this community.” He also said working on the book, starting in late 2010, had been cathartic and productive for him in the wake of his father’s sudden death. He had access to hard copies of the Northfield News and was able to scan them and go over them at his home with his son Bailey, who was then six years old. Bailey was “very fascinated what children would have asked” and “we went through nearly a thousand petitions to Santa. We would read a dozen or two every night; I’d circle the ones I liked. Bailey was my sounding board. I wanted to get a child’s perspective on what works for them more than anything.”

In Introductory Notes to the book, Sauve quoted from a Jan. 3, 1858, letter from Ann Loomis North, wife of Northfield’s founder, John North: “We did not get up a Christmas tree – we cannot get evergreens here. The children hung up their stockings and were quite delighted with the toys and books that old Santa Claus brought.” This explains why one favorite early 20th century request was for Santa to bring Christmas trees, because evergreens are not indigenous to Minnesota.

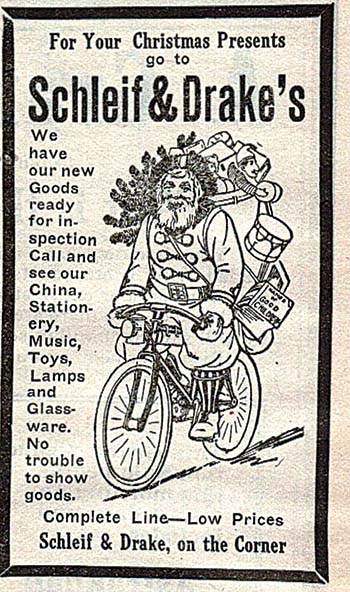

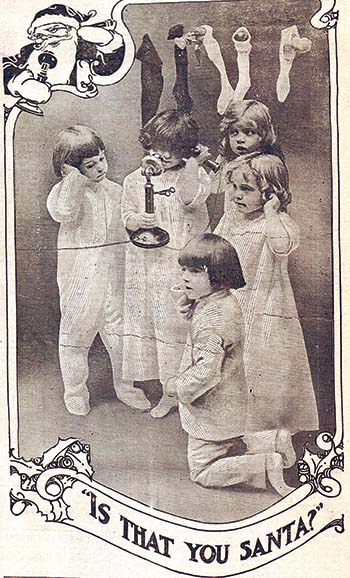

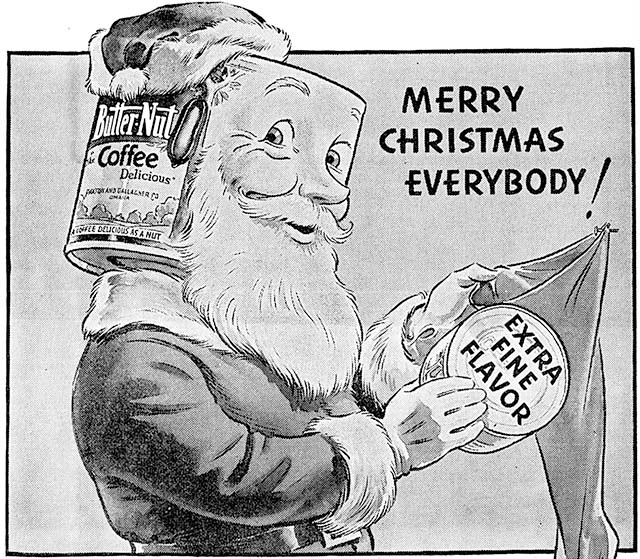

Santa was becoming commercialized by the late 1890s and newspaper illustrations show Santa as adman, including an early ad for Santa Claus Soap out of Chicago, used by “thousands of thoughtful, thrifty women.” A Northfield News ad from Dec. 10, 1898, announced that a “real live Santa Claus will hold receptions at the Bargain Store” which, fortunately for the shoppers, had “Thousands of Toys to delight the children” at prices “unheard of in the history of the Toy business.”

“Letters to Santa Claus” was featured in the Northfield News for the first time on Dec. 20, 1902, with letters from second and third graders. The first one was from Verne C. Gilbert: “I want some games and some toys.” He also inquired, “Do you come down the chimney? I want to know about you.”

Sauve divided Dear Santa into eras, starting with “Golden Age, 1902-1916.” Sauve said, “These divisions between eras were pretty defined really by the social and economic times in the early 20th century.” The arrival of new immigrants could make for different home situations, where children might be staying with grandparents or other family members, with parents off working elsewhere. Some youngsters were at the Odd Fellows Home for children where Three Links is today. All wanted Santa to be able to find them.

Among the letters to Santa from 1902 was one from Jenny Hofstatter, who asked for “a pear of skees,” drum, sled, “sum books and a nice big tree and candy and nuts.” Guy Larson asked for “a twenty-two air riful and two box of bulits,” along with moccasins, a sled, skates and a steamboat. Many children were concerned about the chimney, warning of fires and a slippery roof. One offered to clean the chimney out so Santa would not get dirty on his way down. Although “you are very fat,” Donald Moses assured Santa, “I think you can squeeze through.”

Among the letters to Santa from 1902 was one from Jenny Hofstatter, who asked for “a pear of skees,” drum, sled, “sum books and a nice big tree and candy and nuts.” Guy Larson asked for “a twenty-two air riful and two box of bulits,” along with moccasins, a sled, skates and a steamboat. Many children were concerned about the chimney, warning of fires and a slippery roof. One offered to clean the chimney out so Santa would not get dirty on his way down. Although “you are very fat,” Donald Moses assured Santa, “I think you can squeeze through.”

In 1905, Harold Cole asked for a “rocky horse” so “I can go to California on it.” He told Santa to “be sure to bring me every thing in the store and I will give you any thing you want.” Laura Partlow’s concern was, “Oh Santa we haven’t any snow in Northfield. I am afraid you will have to come in an auto.” (One wonders if she had seen the fourth – and last – car Lincoln Fey had built in Northfield during 1904 and 1905, before giving up due to lack of financial support.)

Unusually warm weather in 1910 prompted Claire Revier to warn Santa of “poor sleighing,” so “Come in your aviator.” In 1912, Marjorie Revier asked for a new head for her doll from last Christmas, because “its eyes have fallen out,” while Hugh Drentlaw wanted a gun, “so I can hunt rabbits. I seen lots of rabbits.” Pearl Miller had a long request list in 1914, including the one used in the title: “Mama wants hat pins, Papa, one mule.” And in 1916, Mabel DeMann reminded Santa that she has a little sister who has “never seen Christmas yet. Don’t forget her.” George Ebling, who said he was eight years old and “Mamma’s only boy” from “a few miles west of Dundas,” wrote, “Please bring me just pie this Christmas. I love pie and lots of it.”

Sauve noted that in the next era, “The Great War, 1917-1918,” children had become aware of World War I accounts of suffering children in Belgium and France. The Dec. 7, 1917, Northfield News announced that Santa was prepared to “bring joy to the youngsters Christmas Eve,” in spite of the war, but “Let’s not forget to be modest in our requests this year as Santa has some heavy back orders to fill among the boys and girls in Europe whose papas are in the trenches or have answered the last call.”

Sauve noted that in the next era, “The Great War, 1917-1918,” children had become aware of World War I accounts of suffering children in Belgium and France. The Dec. 7, 1917, Northfield News announced that Santa was prepared to “bring joy to the youngsters Christmas Eve,” in spite of the war, but “Let’s not forget to be modest in our requests this year as Santa has some heavy back orders to fill among the boys and girls in Europe whose papas are in the trenches or have answered the last call.”

A week later, Eva Winn wrote Santa, “I am glad you are going along again I thoght you would not because of the war… I thoght the germans would shoot you for an enemy…” She asked him not to forget the girls and boys in countries at war.

On Dec. 21, the News printed a letter to the editor from Santa (“in a hurry” from the North Pole). Santa assured everyone that “Mrs. Santa is working hard for the war children, to make up for the loss of home and papa, brother or uncle, by bringing Christmas happiness. So if anyone of my little folks are disappointed and do not get all their heart’s desires, maybe they can be happy in knowing that their playthings have gone to make Belgian and French children happy.” He added this P.S.: “Guess I’ll use my new aeroplane this year. This thaw makes it bad for my reindeers.”

The Armistice of Nov. 11, 1918, ended World War I, but the Christmas season that followed was far from normal because of fears of a flu epidemic. (Sauve said St. Olaf lost four students to influenza about a week after the Armistice.) The Northfield News tried to reassure its readers on Dec. 6: “Now that the world war is over, Santa Claus is on the job with a bigger stock of toys than ever before…The influenza ban will not prevent the delivery of Santa Claus letters and this year prompt service is assured as aeroplane mail delivery is available.” Then, on Dec. 20, the News commented on what a strange Christmas it was, with “old man influenza” and Santa Claus “running in close competition for the attention of people throughout the country.” Large gatherings were banned, so there were no church services and no Sunday School festivities.

Children wrote their requests to Santa, as usual. Margaret DeWolf, age 7, asked for new shoes, a trunk and a little lamp for her bedroom and said, “but be sure to save lots of things” for “the poor war orphans.” Wayne Palon, age 6, started his letter with “I hope you haven’t got the flu,“ before asking for a ball, sled, candy and nuts and “a game or two.”

In the next era, “Roaring Times: 1919-1928,” Sauve noted that with radio and mass marketing of silent movies, children started to ask for things having to do with aviator Charles Lindbergh or with silent film stars like Charlie Chaplin. Among other requests from the 1920s: Milton Donald Blesener sensibly asked for “a real watch not one that says 8:30 all the time,” Helen McCallum (who told Santa her “doggie” Buster died last week) wanted another dog “that looks just like he did,” and Maxine Godberson wondered if the reason she did not get a sleeping doll last year was because “I was a naughty girl for biting my finger nails,” a habit she told Santa she has conquered.

In 1926, Arnold Pleschourt, age 8, wrote to Santa, “Some of the children try to tell me there is no Santa Claus, but I know better and I believe in him: I wish he could come down here and see me. I would like to see the reindeer and the Eskimos.” He asked for a sled, train and jackknife.

“Hard Times, 1929-1940” of the Depression followed. Still, the Northfield News of Dec. 20, 1929, reported that “Santa was in fine fettle when he stepped out of his airplane on Bridge Square Tuesday afternoon” and he was followed in and out of stores “by a crowd of happy youngsters.” Although children of this era asked for many of the usual toys, Sauve told me that, “especially in the ’30s when sound films come about,” the children were “fascinated by radio and movie stars,” such as space character Buck Rogers, singing cowboy Roy Rogers and child actress Shirley Temple, who were “celebrities that appeal to children.”

Sometimes children couldn’t help writing to Santa about the behavior of their siblings. In 1937, Mary Ann Kruegel told Santa that her brother George “hasn’t been any better than last year so don’t bring him too much.” In 1939, Charles Stroebel III requested “a desk of my own too that will lock up so Florence Ann can’t take things from it.”

Sometimes children couldn’t help writing to Santa about the behavior of their siblings. In 1937, Mary Ann Kruegel told Santa that her brother George “hasn’t been any better than last year so don’t bring him too much.” In 1939, Charles Stroebel III requested “a desk of my own too that will lock up so Florence Ann can’t take things from it.”

The final era covered in the book was “World War II, 1941-1945.” Sauve said that while during World War I youngsters were telling Santa not to forget the children affected by war abroad, “Now these children are writing because they have a family member who is serving, whether it’s the Pacific theater or European theater.” Some examples: “…don’t forget our brother Eldred in Iceland and all the other soldiers and sailors;” “Don’t forget my Uncle Lester who is on a ship on the ocean someplace;” “Please don’t forget my daddy in the South Pacific;” “Please take my brother, Don, something. He is near Manila. Hope you find him.” But the children abroad are not forgotten. As one child wrote, “Please give some toys and food and clothes to the boys and girls in the countries where the war is.” Of course, “especially for the boys,” Sauve said, the World War II years created an interest in asking for “rat-a-tat machine guns.”

As always, the children came up with some uncommon requests. In 1942, Kathryn R. Hanson asked for “a real live puppy who will stay little. Do you think you could find one for me?” She gave her phone number and had hopes that anyone who knew of such a puppy would tell Santa. Gifts for pets were also desired: “Can you bring my kitty a new tail?” asked one, and another said, “My kitty would like some liver.” Also in 1942, Donny Peterson wanted a “zoot suit” which could be made to fit him (“I’m kind of small”). One aspiring musician asked for “a four piece swing band.”

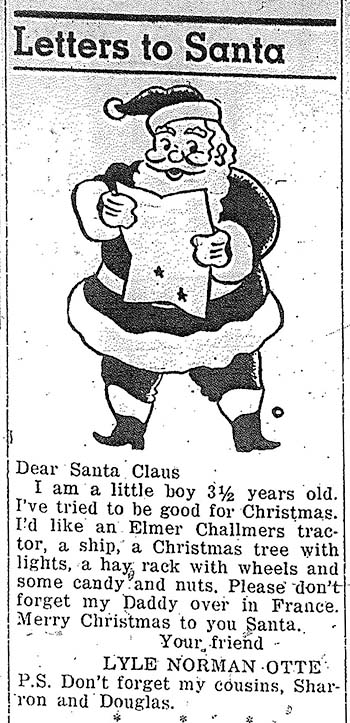

On Dec. 6, 1945, with the war over, the Northfield News wrote about memorial services for Gold Star servicemen of St. Olaf. The story reported that 49 students had “made the supreme sacrifice since Dec. 7, 1941.” While mindful of all who had perished, Northfield prepared for a peacetime Christmas. On Dec. 20, the News published more letters to Santa, including one from a boy whose father had not yet returned from the war. The fulfillment of Lyle Norman Otte’s request of Santa came about in a most unusual manner (see accompanying story on the next page).

The Northfield News continued to publish letters to Santa through 2005. Sauve summed it up: “As one might expect, children of the late 1950s and 1960s clamored for space age toys while those of the later 20th century desired toys based on popular television, movie and video game characters.”

Sauve told me he received an e-mail from a St. Olaf student who was volunteering with others at a local care center. The student said that Dear Santa was being used as part of cognitive memory programs. Students would read some of the letters to Santa aloud and ask senior citizens, “Now what do you remember about Christmases past?” Sauve finds this use of his book very rewarding.

At the end of the book is an alphabetical index of letter writers, from Harold Anderson to George Zanmiller, so that readers might “recognize family names or individuals who later made their mark in the community,” as Sauve wrote. Sauve also wrote that he hoped that “this little volume will provide a joyous reflection of Christmases past as well as a richer understanding of the child’s spirit that resides within each of us.”

Dear Santa is available at the Northfield Historical Society Museum Store, 408 Division St., for $9.95. The other books are Pioneer Women by Jeff Sauve, The Lyceum by Susan Hvistendahl and Electric Theater by Carol Donelan. All are available for online purchase at northfieldhistory.org.

Historic illustrations courtesy Northfield Historical Society and the Northfield News.

“Who Says There Isn’t a Santa Claus?”

This “Letter to Santa” appeared in the Dec. 20, 1945, Northfield News. On Dec. 27, the newspaper reported on what happened next, with the headline, “Who Says There Isn‘t a Santa Claus?”:

This “Letter to Santa” appeared in the Dec. 20, 1945, Northfield News. On Dec. 27, the newspaper reported on what happened next, with the headline, “Who Says There Isn‘t a Santa Claus?”:

“While entertaining some doubts as to the ability of a 3½-year-old to drive an ‘Elmer Challmers tractor,’ the editor of The News forwarded Lyle’s request to the Allis-Chalmers Manufacturing Company, Milwaukee, Wis., largest establishment in its field in the world.” A reply came in the mail from Walter Geist, President, who said he was giving the editor “the pleasure of acting as Santa Claus” by sending a scale model tractor. “All during the war we were stopped from making these models, but his plea was so genuine that I am sending him my own office model, and I hope that you get as much pleasure in acting as the go-between for this boy’s Santa Claus as I am in making this possible.”

I located Lyle Otte, a retired high school social studies teacher, in Decorah, Iowa. He is a graduate of Northfield High School (1960) and St. Olaf (1965). Otte told me that in 1945 he was living with his mother and grandparents on a rented farm near Nerstrand while his father Gerald was away with the U.S. Army postal service in France. After his father returned in 1946, the family moved to Northfield and his father commuted to work for the air mail service at Wold-Chamberlain airport in Minneapolis.

I located Lyle Otte, a retired high school social studies teacher, in Decorah, Iowa. He is a graduate of Northfield High School (1960) and St. Olaf (1965). Otte told me that in 1945 he was living with his mother and grandparents on a rented farm near Nerstrand while his father Gerald was away with the U.S. Army postal service in France. After his father returned in 1946, the family moved to Northfield and his father commuted to work for the air mail service at Wold-Chamberlain airport in Minneapolis.

While Otte has no memory of writing the 1945 letter to Santa (he suspects his mother helped him write it), he has heard how “flabbergasted” his mother was when she heard about the gift. He does remember stopping off at a Federated Store to buy a new pair of blue overalls for a picture taken on Jan. 5, 1946, with Northfield News editor Herman Roe when the tractor arrived. And he has a “partial memory” from about the same age when his “special attachment” to his grandfather Norman Gregerson’s Allis-Chalmers tractor almost ended in tragedy. He said, “I climbed up on the tractor, parked on a hill.” Somehow he released the brake, causing the tractor to start to roll down the hill. “Grandpa came running and jumped on the tractor, pulled the brake lever and managed to stop it.”

Perhaps Santa Claus was looking out for him.