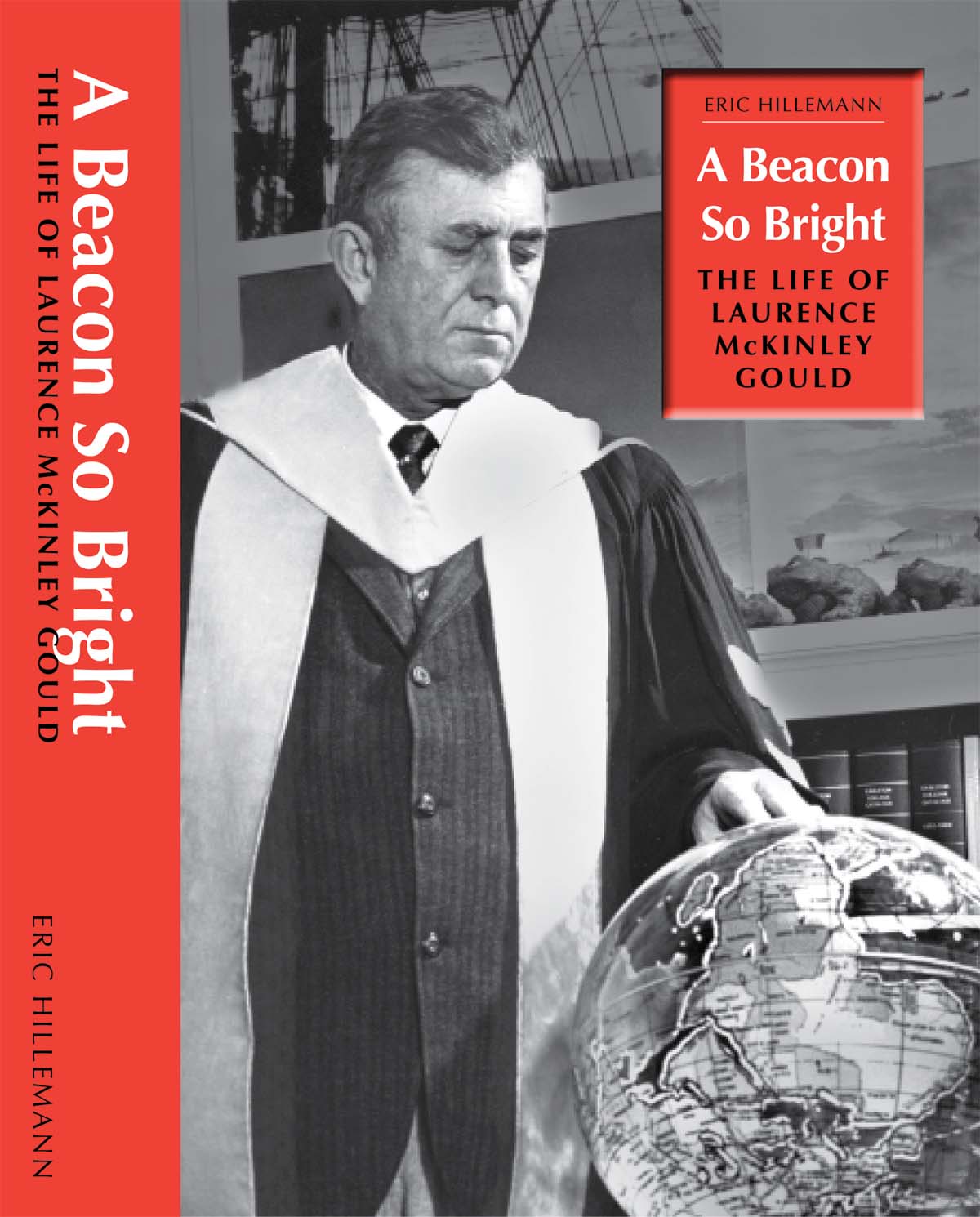

Last month Carleton College published A Beacon So Bright: The Life of Laurence McKinley Gould, a long-awaited biography of Carleton’s fourth president by Carleton archivist Eric Hillemann. In last month’s Entertainment Guide, I wrote of Gould’s life up until he accepted the presidency in 1945, a life already filled with adventure and achievement.

To recap: Gould, a native of Michigan, had earned advanced degrees in geology at the University of Michigan and, after a couple Arctic explorations, was selected to be second-in-command of Admiral Richard E. Byrd’s 1928-1930 historic expedition to the Antarctic. This expedition was highlighted by Byrd’s flight across the South Pole and a two-and-a-half-month dog sledge journey led by Gould over dangerous and icy terrain to previously unexplored land. As Hillemann told me, “Gould came back a national celebrity” and, with other expedition members, was honored with a ticker tape parade in New York City and a welcome by President Hoover in Washington, D.C. Gould embarked on a nationwide lecture tour which brought him to Carleton for the first time on Oct. 14, 1930. Gould was hired to be head (and only member) of Carleton’s newly formed geology department two years later and quickly established himself as one of the college’s most popular professors. The students took note of his colorful neckwear and held “Wild Tie Days” in his honor, with the predominant color being Gould’s favorite – red.

After spending three semesters heading up the Arctic, Desert and Tropic Information Center of the Air Force during World War II, Gould returned in the fall of 1944 and on May 12,1945, Gould was selected by the trustees to succeed Donald J. Cowling as president of Carleton. The victory bell was rung at Willis Hall and students celebrated by wearing bright red clothing the next day.

Despite Gould’s popularity, his selection did not come easily, as Hillemann documents in his book. Hillemann told me that Gould’s educational philosophy was not apparent since Gould’s writings had been about scientific topics and he had “no significant fund-raising or college administrative” experience.

From the start, Gould felt there were “too many courses, too many departments, too many majors” and proceeded to make changes. The war was over, the GI Bill brought an influx of veterans to campus and new buildings were needed, including library and fine arts buildings. Continuing to be a speaker in demand, Gould gave more than 70 speeches in his first year in office, including nine commencement addresses, on diverse topics.

Gould focused on bringing in quality faculty and Hillemann notes in the book that at the end of only 13 months in office, Gould had “personally hired fully 46 percent of his present faculty.” (This would increase to 90 percent by 1960.) Hillemann told me he felt that Gould’s most remarkable accomplishment was his “judgment about people” in the hiring that he did. “He brought some very successful people to Carleton, young people with potential…The spirit at Carleton during his years was just consistently high, the college was getting better and better. They loved their leader.” An inspiring speaker, Gould “could capture people’s imagination. He set his sights high, both personally and for Carleton,” so striving for excellence was “just always to the fore.” Even by 1950, the Dean of Yale College was listing Carleton among the “distinguished small colleges” which constituted a “lively crop of rivals.”

Gould’s popularity continued unabated. There were annual campus-wide celebrations of the date Gould was named president, with the city of Northfield contributing a red fire truck to carry Gould and red-attired students to the festivities. At the end of the day, Larry and Peg Gould were serenaded at their home, with songs such as “Red Red Robin.”

On Sept. 16, 1952, seven weeks before the U.S. presidential election, Gould gave the official welcome to candidate Dwight David Eisenhower before more than 10,000 packed into Laird Stadium for a campaign rally meant for students. “Ike” had words of praise for small colleges for preserving “the values that have made our country great and which in turn we must apply if we are going to lead the world toward peace, security and prosperity.” (Hillemann told me that Gould was a Republican up to the 1964 presidential election, as was the campus, according to poles. By 1964, both the college and Gould favored Democrats. Said Hillemann, “He was always in sync with Carleton.”) In the fall of 1953, Eisenhower appointed Gould to the National Science Board of the National Science Foundation. Gould also became a trustee of the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching and of the Ford Foundation and from 1958 to 1961 served as president of the United Chapters of Phi Beta Kappa.

Gould had presided over a decade of progress by the spring of 1955. College assets had risen from $5.68 million to more than $11 million, with a marked increase in endowments and alumni support. The next year on May 22, a thousand volunteers transferred the contents of the old Scoville Library to the brand new one, a major achievement of his fund-raising activities. Gould had chosen the wood-carved quotation above the lobby (now located in the reference room) from Norwegian explorer Fridtjof Nansen: “The history of the human race is a continual struggle from darkness toward light. It is therefore to no purpose to discuss the use of knowledge. Man wants to know, and when he ceases to do so he is no longer man.” The official dedication was held on Sept. 22,1956, with poet and Librarian of Congress Archibald MacLeish as speaker. MacLeish declared: “One more bulwark has been raised against ignorance and bigotry and fear: a tower which will not yield.”

Gould returned to visit Antarctica late in 1956 and in March of 1957 was awarded an Explorer’s Medal in New York, an honor his idols Amundsen, Nansen and Byrd had also received. Gould was director of the U.S. Antarctic program for the International Geophysical Year of 1957-1958. Hillemann told me Gould considered Antarctica his “spiritual home” and was dedicated to seeing that the continent should be “devoted to peaceful purposes and international cooperation.” In February of 1958, the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR) was created with Gould as the U.S. delegate and an Antarctic Treaty which set aside Antarctica as a scientific preserve was ratified on June 23, 1961. Gould wrote that it was the cooperative efforts in Antarctica, “coldest of all the continents, that witnessed the first thawing of the cold war.” (Gould went on to serve as president of SCAR from 1963-1970.)

Hillemann told me that Gould passed up many opportunities to leave Carleton, some quite lucrative. In July of 1958, while Gould was at his vacation home in Wyoming, President Eisenhower offered him “the opportunity to be the first director of a new government agency that would be established, which shortly thereafter got the name of NASA” (the National Aeronautics and Space Agency). Gould was in the process of a multi-million dollar fund drive for Carleton and turned it down.

The fundraising was greatly aided by the Olin Foundation giving $1,500,000 for the Olin Hall of Science, the largest single gift in Carleton’s history, announced on Feb. 6, 1959. (The building, one of several on campus designed by Minoru Yamasaki, was dedicated Oct. 14, 1961. Yamasaki became the architect of the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center in New York City which were destroyed on Sept. 11, 2001.)

As Gould’s presidency was nearing its last year, a feature article in the Chicago Tribune of Feb. 25, 1961, called Carleton “a little Harvard,” highly exclusive and “dedicated to an aristocracy of intelligence and character.” Credit was given to Gould for having in 15 years “assembled a teaching staff of extraordinary distinction,” increasing the average faculty salary by 248 percent.

Gould announced that he would be retiring in 1962 and the trustees elected John W. Nason (Carleton Class of 1926) to be Gould’s successor. Nason had been president of Swarthmore College 1940-1953 and was president of the Foreign Policy Association in New York. On April 12, Larry Gould Day was declared in Northfield with a “red tie” banquet at the St. Olaf Center attended by 500 friends and neighbors, the “largest testimonial dinner in town history,” despite a spring snowstorm that night. In perhaps the ultimate compliment, St. Olaf announced that Gould would be made an honorary Ole at commencement. In June Carleton students presented the Goulds with round-trip tickets to Athens and the faculty gave them a red jeep for use on their Wyoming property.

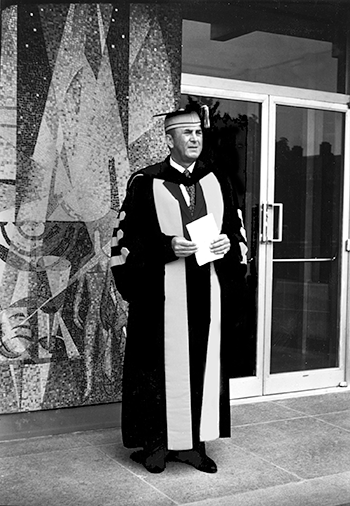

At the 17th and last commencement of Gould’s presidency, Gould was the speaker, at the invitation of Carleton’s Class of 1962. Completion of a $12 million four-year development drive was announced and Gould was surprised to be made an “official alumnus by conferring upon him the Degree of Doctor of Humane Letters.”

The Goulds then made their home in Tucson, Arizona, for 32 years. Gould taught at the University of Arizona (creating and directing the College of Earth Sciences in 1967) and helped start Prescott College. He also served as President of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Gould was a popular presence at Carleton alumni events and continued to give speeches throughout the country. In one address in 1967, Gould commented on the campus unrest of that era: “The courage of dissent is part of the responsibility of the intellectual but it carries with it the reciprocal responsibility of listening.” He began to speak on environmental threats posed by overpopulation and pollution and wrote that man is “fouling his own nest” and “for the first time in history the chief danger to our survival comes from ourselves instead of the forces of nature.” Hillemann told me Gould was “worried about our stewardship of the globe” and surely would be weighing in on the topic today, “now that chunks of the Antarctic ice cover have just broken off and are gone.”

Gould once said that his “recipe for retirement” was “Winter in Tucson, summer at Jackson Hole, with an occasional visit to Antarctica.” Hillemann writes in his book that the year 1979 brought “multiple lasts” – Gould taught his last class, spent a last summer in Wyoming and in November, at the age of 83, went to Antarctica for the seventh and last time for the 50th anniversary of Byrd’s flight over the South Pole. In May of 1982, the University of Arizona gave him his 26th and last honorary degree. In 1987, Gould made his last trip to Northfield to a reunion of the Class of 1962 – their commencement was the last he had presided over. (This class made news in 2012 by giving a record $30 million gift to Carleton at its 50th reunion.)

Gould’s wife, Peg, died in July of 1988 and her ashes were scattered on Carleton’s Lilac Hill by friends. Gould died June 21, 1995, two months shy of his 99th birthday. Hillemann notes in his book that “June 21 is the first day of winter in Antarctica, the darkest day of the year.”

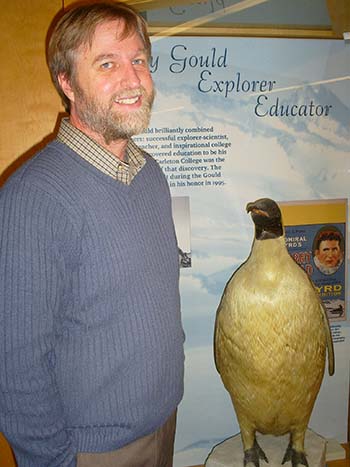

Carleton held a convocation on Oct. 13, 1995, in Skinner Memorial Chapel, where Gould had been inaugurated as president 50 years before. On stage was a 70-pound stuffed emperor penguin called Oscar which Gould had brought back from his first trip to Antarctica. This bird had remained “a fixture of successive Gould homes throughout his life.” The penguin was wearing a bright red tie.

President Lewis announced that the Carleton library would henceforth be called the Laurence McKinley Gould Library. (Oscar is now in permanent residence in a special case in the library.) Hillemann told me, “I thought it was absolutely dead-on perfect for the library to be named for him” since Gould himself had called the library the heart of the college.

After the convocation, a small group went out to spread Gould’s ashes where his wife’s ashes had been scattered seven years before. In his eulogy, Professor Tony Obaid said, “Every spring you both will return to life with leaves and flowers of this sacred lilac hill.”

Gould’s name can be found on a geosciences building at the University of Arizona, in addition to Carleton’s library. A National Science Foundation polar research vessel and several polar geographical features bear his name. Hillemann hopes his biography will keep Gould remembered as well.

“He’s worth knowing about,” Hillemann said to me. “If there is any theme to my book, it’s that however you are going to define greatness, Larry Gould had it.” Hillemann concluded, “His relevance to today is summed up in the title, A Beacon So Bright: The Life of Laurence McKinley Gould. I think that his life is a shining example of what a human life can be, an extraordinary life – a model of how a good life can be led. He is worthy of emulation as a hero.”

Thanks to Eric Hillemann for his customary cooperation with my stories.