Two years after the Nineteenth Amendment granted women the right to vote, Minnesotans had the chance to vote for the first woman ever to be endorsed by a major political party for the office of the U.S. Senate in the election of 1922. Anna Dickie Olesen, whose name was once known from coast-to-coast in political circles and praised nationwide by the press, spent a good part of her life in Northfield. She counted among her friends some of the most well-known Democratic politicians of her time, from renowned orator and three-time candidate for president William Jennings Bryan to four-time elected president Franklin Delano Roosevelt. She was even considered a candidate for the vice presidency.

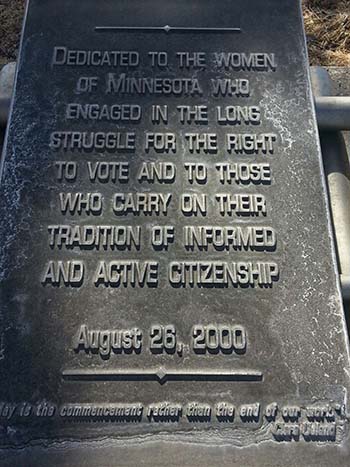

But today her name has been largely forgotten except by those who have encountered her name at the Minnesota Woman Suffrage Memorial Garden at the St. Paul Capitol dedicated in 2000 and by readers of Richard Jay Hutto’s truth-is-stranger-than-fiction book about her second husband, Chester Burge, called A Peculiar Tribe of People: Murder and Madness in the Heart of Georgia (Lyons Press, 2011). More on that later below.

Anna Dickie was born to Peter and Margaret Jones Dickie on July 3, 1885, on a farm near Waterville, Minnesota. According to Dolores De Bower Johnson’s essay about Anna in Women of Minnesota (Minnesota Historical Society Press, revised 1998), Anna’s drive may have come from her ancestry, “which included some unusually strong-minded and independent women” like Margaret Hughes Davis who had been part of an Ohio colony of Welsh immigrants before moving to southern Minnesota. Anna grew up in a home where books and education were valued. Precocious and talkative, Anna was coached in public speaking when she was only 12 by a family friend. After attending country school, Anna walked or took a horse three miles to attend Waterville High School.

After graduation, Anna taught briefly before marrying Peter Olesen. Olesen had come through the area selling books to help finance his education at Hamline University and was one of many travelers her father had offered hospitality to at their home. Olesen, a native of Denmark who had come to the U.S. at the age of 15, served in the Spanish-American War in 1898. The couple married on June 8, 1905, the day after his graduation. Olesen went on to earn a master’s degree at Hamline in 1908. He became superintendent of schools in Pine City in 1906 (where their daughter Mary was born in 1907) and they moved to Cloquet in northern Minnesota where Olesen was superintendent of schools for 14 years.

Johnson described Cloquet as a “lumbering town populated by a work force of immigrants of various nationalities, along with mill owners and managers.” Anna became “painfully conscious that she did not have an impressive house and that her clothes were not as elegant as those of the wives of the businessmen who would determine her husband’s success.”

Anna began an involvement with the Women’s Club, teaching English to immigrants and joining in on the fight for women’s voting rights, her first step into politics. According to Johnson, woman’s suffrage was “representative of the causes she was to espouse throughout her political career: Prohibition, child and social welfare programs, opposition to large corporations and special interests, and, later, support for the Social Security Act and other New Deal legislation.”

In her run for the U.S. Senate, Anna was driven across Minnesota in a Ford sedan donated by her supporters. Giving as many as six speeches a day, she attacked the Republican incumbent and said, “I ask no consideration because I am a woman. I also ask that no one close his mind against me because I am a woman.” Her campaign drew national attention after she defeated two male opponents in the primary of June 19, 1922. Courtesy of the Carleton College Archives.

By 1913, Anna had been elected president of the Federation of Women’s Clubs in Minnesota’s Eighth Congressional District. In 1914, she was appointed a delegate to the International Child Welfare Congress in Washington, D.C., and in 1916 was elected state vice president of the Women’s Clubs, a position she held for two years. After an “electrifying” speech on suffrage at the state convention of the Minnesota Democratic party in 1916, she was appointed the Minnesota member of the women’s advisory committee of the Democratic National Committee in 1917, serving until 1924.

Renowned orator and former Democratic presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan accompanied Anna during her campaign, including stops before overflow crowds in Northfield on Oct. 17, 1922, at the Community Club and at Carleton’s Skinner Memorial Chapel. Anna’s message: “Eventually a woman member of congress from Minnesota, why not now?” Carletonian courtesy of the Carleton College Archives.

Anna had convinced her husband that they should hire a maid and pay a dressmaker for her “public clothes” and, to help pay for these amenities, Anna and her daughter Mary went to Libertyville, Illinois, in the summer of 1918 so Anna could try out for the Chautauqua. This was a touring adult education movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries which brought entertainment and culture to communities, often featuring speeches in tents on such topics as temperance, women’s suffrage and child labor laws. It turned out that Anna Dickie Olesen, with her oratorical flair and passion for such subjects, was uniquely qualified and she began an association which would last more than ten years and bring her a friendship with the most popular Chautauqua lecturer, William Jennings Bryan.

On Oct. 12, 1918, an unimaginable forest fire destroyed practically every home and five of the six public schools in Cloquet, a city of 9,000 inhabitants. The St. Paul Pioneer Press of Jan. 12, 1919, credited the reopening within four weeks of the one school that remained (with double shifts for the 800 students) to the “splendid spirit of co-operation that has prevailed between Superintendent Peter Olesen and his teaching corps.” The article noted that Olesen, his wife and daughter were living in a cloak room, “just large enough to contain sleeping quarters and a dresser, a chair and a few other meager furnishings, but they are happy and determined to ‘stand by.’”

While her husband was working to resurrect the Cloquet school system, Anna was gaining political recognition. In January of 1920, she became the first woman to address the Jackson Day Banquet in Washington, D.C., on the subject of the party’s ideals. The Washington Herald proclaimed, “Small in stature, she proved herself a forensic giant.” The World’s Work magazine said that “vitality, magnetism and charm” radiated “so richly and strongly you could almost see the rays darting out over the audience.” The Omaha World Herald wrote it was a “moment of real triumph for womankind” when “the entire audience came reverently to its feet.”

The next month Anna spoke to the National Woman Suffrage Association in Chicago. The Minnesota state party elected her a delegate to the national Democratic convention in San Francisco where she was the floor manager for Prohibition supporter William G. McAdoo, Woodrow Wilson’s son-in-law. Anna, introduced by William Jennings Bryan, spoke “in the name of the motherhood of America” in favor of Prohibition and, although the convention nominated the anti-Prohibition candidate, James M. Cox and his running mate, Franklin D. Roosevelt, her speech was well-received. Republican Warren G. Harding won the election but Anna gained favor as a great woman leader of her party.

Although stories differ about how it came about, Minnesota Democrats in 1922 endorsed Anna Dickie Olesen of the Democratic National Committee as candidate for the U.S. Senate seat held by Republican Frank B. Kellogg. Anna was the first woman ever nominated by a major party for U.S. senator.

Johnson wrote that Anna ran a “determined and hard-hitting” campaign as she “crisscrossed the state, speaking to as many as six audiences a day and repeatedly attacked her Republican opponent.” Anna’s brother Owen drove her around the state in a Ford sedan donated by her supporters. She kept expenses low by staying with friends along the way and accepting donations. In Washington, Sen. Kellogg was asked why he did not return to Minnesota to campaign. When he reportedly answered, “I’ve got some Swede woman running against me,” his questioner said, “That’s no Swede woman, that is a Welsh woman and the devil rides her tongue. You’d better go back to Minnesota.”

Anna tallied 28,745 votes in the June 19 primary, winning handily over two male opponents. In her campaign speeches for the Senate, Anna said, “I ask no consideration because I am a woman. I also ask that no one close his mind against me because I am a woman.” But because she was a woman (with newly enfranchised female voters), her campaign drew national attention. The New York Evening World said, “She has an excellent voice, personal magnetism and feminine charm backed by good sense and idealism.” A reporter from the Chicago Herald and Examiner followed her for a week as she visited six counties and marveled as “this wonder woman” turned skeptics into “ardent, shouting, cheering and sometimes happily tearful adherents” by the brilliance of her oratory.

When Anna was nominated, she had promised to stand for the “common people, the true democracy of the land,” and when her campaign took her to Northfield, she brought along her friend from the Chautauqua circuit, William Jennings Bryan, nicknamed “The Great Commoner” for his belief in the wisdom of the common people.

Bryan had been the Democratic candidate for president in 1896, 1900 and 1908 and was a renowned orator. The Northfield News of Oct. 20, 1922, said that although Bryan, “aged tho he looks, yet picturesque withal, may have been the drawing card” for the two appearances at a Community Club luncheon and then at a capacity gathering at Carleton’s Skinner Memorial Chapel, “Mrs. Olesen’s personality, wit, and eloquence had so completely won her audiences as to almost over-shadow the appearance of the ‘peerless one’ himself.” At Carleton, Anna threw down her challenge: “Prejudice is an enemy to human progress, whether it be religious, party or sex prejudice. There is not a country in the civilized world which does not give women some voice in government…Eventually a woman member of congress from Minnesota, why not now?” Bryan proclaimed, “I don’t know any man or woman I would rather see in the Senate than Mrs. Olesen.”

On election day, Nov. 7, Anna did not win but neither did the Republican incumbent. Henrik Shipstead of the emerging Farmer-Labor party won with 325,372 votes to Kellogg’s 241,833 and Anna’s 123,624. (The Farmer-Labor party voiced Minnesota’s agricultural concerns and ultimately merged with the Democrats to form the DFL in 1944.)

Anna’s Senate race led to more lecture bookings for her, on topics such as “Women and Progress” and “Pioneering in Politics.” But she would soon have a new base of operations. The Duluth News Tribune of Feb. 11, 1923, announced that Cloquet had “risen from the ashes” and “its famed schools stand complete” due to the “persistence and energy of Peter Olesen.” With the completion of that task, Olesen announced his resignation as superintendent and joined the faculty of Carleton College in the fall of 1923 to teach German and serve as registrar, with daughter Mary enrolling at Carleton.

Anna told the Northfield News on Aug. 24 that she had visited hundreds of towns in the U.S. and, “Whatever little I can do in my lecture tours to boost the city of cows, colleges, and contentment I shall proudly do for there is no place like home and Northfield seems that to me already.” She was pictured with a caption saying that her entry in Who’s Who would add “further distinction to Northfield which claims the largest per capita representation in Who’s Who of any city in the state.”

Although Anna did not involve herself with Carleton at all, by October she was promoting the League of Nations in a speech before the Northfield League of Women Voters. In April of 1924 she was the principal speaker as 64 members of the St. Paul Business and Professional Women’s club and three business women of Farmington were guests at Northfield’s regular meeting. (The Northfield News account of April 11 said the program included a “typewriter speed demonstration by Miss Minnie Regelmeyer, the world’s champion amateur typist.”) Johnson wrote, “Because of her lecture fees, Anna now had a measure of economic independence” and could “gratify her desire for fine things.” The Olesens traveled to Canada, Mexico and Europe, including a stay at the Univ. of Heidelberg in 1928 where Peter got a certificate in German.

In 1932 she was chosen as one of the Minnesota delegates-at-large to the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. She supported Franklin Delano Roosevelt and delivered a stirring seconding speech for John N. Garner for vice president and then campaigned for the winning ticket.

Anna was rewarded for her loyalty with the position of acting postmaster of Northfield, effective Dec. 1, 1933. But shortly thereafter in January of 1934, Pres. Roosevelt appointed her as the only female state director of the National Emergency Council (NEC), a federal division which coordinated programs of various New Deal agencies. When her post was eliminated in 1942 as an economy move, she was one of only two of the original 48 state directors still in service.

In 1949, Peter Olesen retired from Carleton at age 70 and Peter and Anna moved to Macon, Georgia, where Peter taught German at Mercer University for five years. They then returned to the home they had kept in Northfield. Peter died at age 81 on Aug. 5, 1960, of a heart ailment he had suffered for five years.

On April 5, 1961, Anna married a man she and Peter had known in Macon.

Chester Burge was 57, Anna was 75. Johnson wrote, “Burge was a wealthy, controversial, and somewhat mysterious man. Their life together was brief. In October, 1963, he died from burns after an explosion in their residence in Palm Beach, Florida, while his wife was in Northfield closing up her house for the winter.”

Anna, a convert to Catholicism, had found “some solace” in her new religion, according to Johnson, but once told her daughter, “Every horse has been shot out from under me.” She may well have been disappointed at the “failure of her candidacy to open the floodgates for women in politics.” (Indeed, it was not until Amy Klobuchar took an oath on Jan. 4, 2007, that Minnesota had a woman in the U.S. Senate.)

Johnson wrote that the Northfield house was filled with “antiques from the estate of Episcopal Bishop Henry B. Whipple and furniture and ojets d’art reputed to be from castle of the mad King Ludwig of Bavaria.” But it seems Anna found less pleasure in material goods as she aged. Among passages Anna had copied out from works that had meaning for her was this one from Edna St. Vincent Millay’s Siege: “This I do, being mad;/ Gather baubles about me,/ Sit in a circle of toys, and all the time/Death beating the door in.”

Anna remained in Northfield until her death on May 21, 1971, at the age of 85, a few weeks after a fall. She is buried beside Peter Olesen in Sakatah Cemetery in Waterville.

A Few Local Memories of Anna and Chester

Clifford and Grace Clark bought Anna’s three-bedroom house at 718 4th St. East from Anna’s brother in August of 1971. The house had not yet been cleared of its furnishings and Clifford told me there was a “wild collection of stuff.” Clifford, a Carleton history professor, remembers seeing the signed photographs she had from Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt. There was an 8 foot by 8 foot framed picture of Christ on the cross in the dining room, German steins, a Shaker rocker, a marble table top with two sitting full-size ebony whippets as supports. The Clarks still have the crystal chandeliers on the first floor and upstairs bedrooms which Peter and Anna Olesen bought in Czechoslovakia in 1936.

Mary Lou Crow, a Northfield resident for 50 years, used to live across the street from Anna. Mary Lou was a nurse at Northfield Hospital and was hired by Anna’s brothers in Waterville to help her fill her syringes for insulin injections once a week. Mary Lou describes Anna as a “very intelligent, very sharp woman, very much her own person.” She remembers Anna having a caretaker from Waterville, an 81-year-old man, who cooked for her and took care of her yard. Anna had “a big jar filled with dollar bills” which she “handed out for the service people.” There were many antiques in the house and Mary Lou hoped there might be an estate sale, “but a big van came and everything was gone.”

Betsy Bierman has lived at 409 Elm Street since 1952. She and her husband John (both graduates of Carleton College) raised their 12 children there and she told me, “Our children were not to step off the sidewalk onto her lawn. She was not very neighborly, except when her grandchildren came and she wanted playmates for them.” Betsy remembers Anna’s first husband Peter as very friendly but said her second husband Chester “was the weirdest man I ever saw.” Betsy recalls hearing that Anna had told people that Chester “took me to the gates of heaven” and she showed off big jewels Chester had given her which neighbors thought were probably fake. Betsy said that Chester and Anna would spread blankets out in their back yard to sun themselves. They had two parrots with them which got dunked in a water pail if the birds got too obstreperous. Betsy also said that Carleton had banned Chester from using the college gym because he was “too interested in the boys.” (There is a memorandum in the Carleton Archives dated June 30, 1965, that Anna had called to give the departing dean “startling material” on “improper behavior involving a number of faculty members and administrative officers, including her former husband.” The dean declined to meet with her.)

When Anna died on May 21, 1971, Betsy Bierman and Mary Lou Crow went to pay respects at Anna’s home where her body was displayed beneath the giant framed picture of Christ on the cross.

It was the only time Betsy had been inside the house of her neighbor.

The Strange Saga of Anna and Chester Burge

The marriage announcement in the April 13, 1961, Northfield News said that Anna Dickie Olesen’s new husband, Chester Burge, was a retired investment broker who “spends much of his time in travel, having visited Europe 12 times.” On April 20, Carleton’s president Larry Gould wrote a letter to Anna at her Northfield home after the newlyweds visited his office: “It is always reassuring to see people so obviously happy and your perennial good spirits seemed at their best. I am sure you will have many happy years together.” It was not to be.

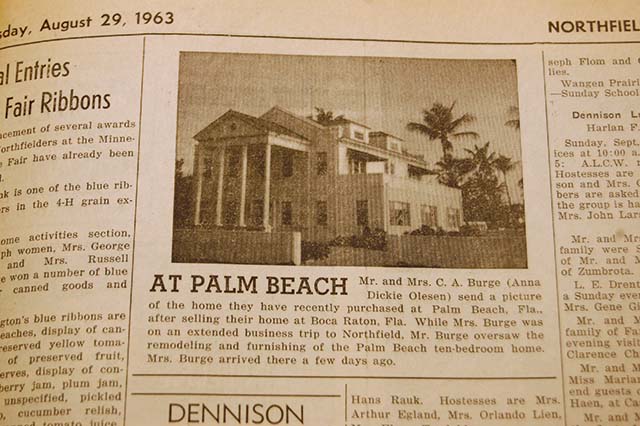

The August 29, 1963, Northfield News had a picture of the Burges’ ten-bedroom home in Palm Beach, Florida. At 3:30 a.m. on Oct. 7, 1963, this house exploded and Chester Burge died of his extensive burns. There were rumors the explosion may have been intentional. Some even felt that Burge had “gotten what he deserved.”

Burge’s story is told in Richard Jay Hutto’s book, A Peculiar Tribe of People: Murder and Madness in the Heart of Georgia, published in 2011. Hutto, who served as White House Appointments Secretary to the Carter family and is a historian of the Gilded Age, lives in Macon, Georgia. He relates the sordid, not gilded, tale of Burge, the black sheep outcast of the wealthy Dunlap family of Macon, who got his money as a bootlegger (serving a year in prison) and slumlord who preyed upon indigents. Chester latched onto a remaining rich relative, got her to rewrite her will in his family’s favor and, when she conveniently and perhaps suspiciously died three days later, acquired wealth and attempted, unsuccessfully, to acquire social prestige with his wife Mary as well.

On the morning of May 12, 1960, while Chester was in the hospital after hernia surgery, the Burge family maid found the body of Mary Burge in her bed. She had been strangled and the medical examiner said that the finger on which she wore her large diamond was “almost severed from the hand, apparently in an effort to remove the ring.”

Was it a robbery? Could the killers have been the Ku Klux Klan, which had gathered on the Burge lawn two weeks before to protest Chester renting to a black family in a white neighborhood? Was it coincidence that the Burges’ sentry-like squawking pet parrot had been found bleeding and dying in its cage the previous afternoon? Did it mean anything when Mary paid off her neighborhood grocery account earlier than usual saying, “I want to get everything in order,” as if she knew something would happen? Had Burge somehow managed to sneak out of the hospital to kill his wife? Had he contracted someone else to do the deed? If so, what was his motive?

The police thought Mary, in whose name much of their holdings were, was interfering with his plans to finance a future with one of his male lovers. Burge was put on trial after hiring a topnotch legal team for $50,000 and was acquitted of murder when the jury was able to overlook his character flaws, believing there was not enough evidence against him. But he was found guilty of another charge: sodomy with his African American chauffeur, Louis Roosevelt Johnson.

Thus, when Anna married Chester Burge on April 5, 1961, the newlyweds were awaiting word on that appeal. Anna told reporters, “I know the whole story about the Macon case. Nothing has been concealed. The other charges are false, and we will fight it to the U.S. Supreme Court.” She declared, “Mr. Burge is one of the finest gentlemen I have ever known.”

Hutto asks the obvious question, “What would lead a woman of Anna Dickie Olesen’s accomplishments to marry Chester Burge, 18 years her junior, tried for his own wife’s murder, convicted of sodomy, and awaiting an appeal?” What hold did Chester have on her? Years earlier, Anna had helped the Burges carry out a kidnapping of her own granddaughter, Anne Gerin, to marry John Burge, the son of Chester and Mary. Anna finally helped Anne flee from that situation. (Yes, this is stranger than fiction.)

Hutto quotes Anna’s grandson, John L. Gerin (a respected professor of microbiology and immunology at Georgetown Univ. Medical Center): “He was a swashbuckling, charming Southern gentleman, exciting and flamboyant” and she was “a very loyal person to whomever she was committed.” John Gerin’s sister Anne, the one who had been kidnapped, agreed Chester swept Anna off her feet and that both of them “lit up a room when they come in and everybody notices.”

When the Georgia Court of Appeals heard arguments in May, the sodomy conviction was overturned for lack of corroborating evidence that the chauffeur was coerced. Anna and Chester were free to pursue their shared love of material possessions, including antiques and fine furnishings, in Northfield and in Florida. They sold a house in Boca Raton to attempt social climbing in Palm Beach in the grand beach house where Burge met his fate.

Hutto recounts a “frantic” trip Anna took in August of 1963 to Macon to inquire about Chester’s past in which she took the advice of both the police and a psychiatrist from the murder trial to go to her home to Minnesota rather than return to Palm Beach. The caption of the August 29 Northfield News picture of the Palm Beach home indicates she did go to Palm Beach in August. But, at any rate, she was back in Northfield at the time of the explosion on October 7.

The Macon News reported that the roof was blown off by the explosion, with glass scattered in all directions. A patrolman saw Burge running across the front lawn, aflame. Burge died, horribly burned, in the hospital. A gas heater leakage was suspected, but Hutto discovered “the gas had not even been turned on at the location that was first suspected of being the source of the fire.” There are indications it could have been a professional hit with dynamite.

Hutto, for one, believes Chester had Mary killed, whether he was present at the actual murder or not. Could the explosion be linked to that murder? Two unidentified men visited Chester at the hospital the night Mary was killed. Had they been hired by Chester? Did they seek revenge when he did not pay them? Those questions, along with many other conundrums in this book about a “peculiar tribe of people,” remain unanswered.

Hutto, a ninth generation Georgian, chose an intriguing epigraph by Flannery O’Connor for his book: “I have found that anything that comes out of the South is going to be called grotesque … unless it is grotesque, in which case it is going to be called realistic.”

What does one say about the strange saga of Minnesotan Anna Dickie Olesen, who went from iconic empowered female to wife of the notorious Chester Burge? As Hutto e-mailed me, “I can’t wrap my head around the concept of Anna’s being wrapped up with this warped man.”

Neither can I.

My thanks to author Richard Jay Hutto for his assistance with this fascinating and ultimately perplexing Historic Happenings subject.