Northfielders reading Reed Whittemore’s memoir Against the Grain: The Literary Life of a Poet (Dryad Press, 2007) may have an irresistible urge to start with Chapter 7, “Out in Minnesota,” which tells of the years from 1947-66 when he taught at Carleton College. However, they will probably first read the foreword to the book, written by Garrison Keillor.

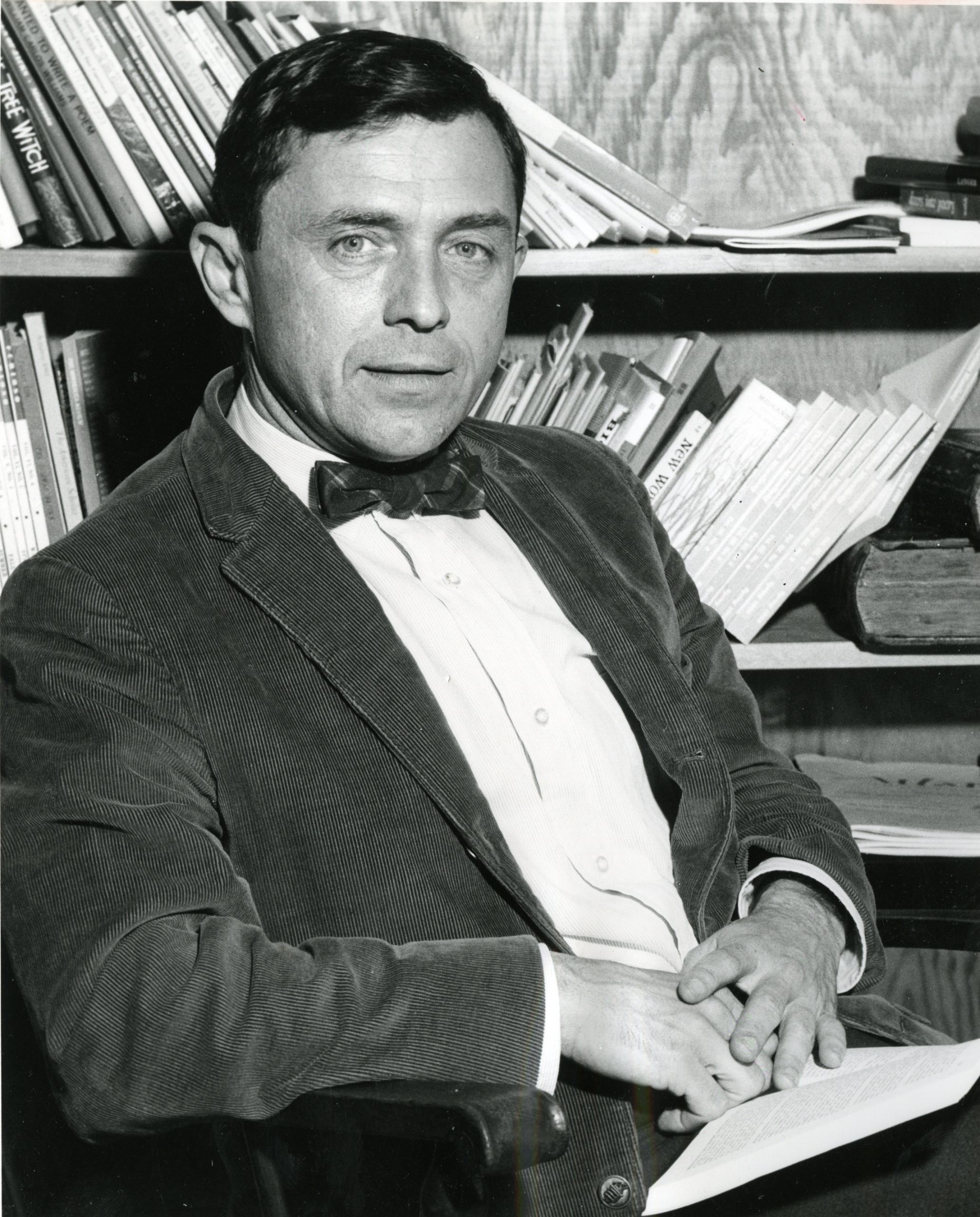

Keillor wrote, “Reed Whittemore owns the only sort of immortality that matters to a writer, which is to have written things that people remember years later.” For example, “There is the perfect imagist poem about the enormous silence that follows after a high school band finishes practicing on the football field in a small town.” (That small town would be Northfield.) Keillor says that what makes Whittemore “permanently readable and relevant is his wit and humor, which is the underground spring that keeps the gardens of American literature green.” Keillor took a class from this “movie-star handsome poet and teacher” in Minneapolis in July of 1964 and fell under the spell of Whittemore’s poems.

The book jacket of Against the Grain summarizes some of Reed Whittemore’s achievements: author of 20 books of poetry, criticism, biography and literary journalism; consultant in poetry to the Library of Congress (now known as the U.S. Poet Laureate); nominee for the National Book Award for poetry for The Mother’s Breast and the Father’s House; founder of two respected literary magazines, Furioso while a student at Yale and the Carleton Miscellany during his 19-year career at Carleton; teacher at the University of Maryland; literary editor of the New Republic; biographer of poet William Carlos Williams; recipient of the National Council of the Arts Award for lifelong contribution to American Letters and Award of Merit Medal from the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

Reviewing Against the Grain for the Minneapolis Star Tribune of Nov. 18, 2007, Keith Harrison (English professor and writer-in-residence at Carleton 1968-1996) noted that Whittemore is “one of a handful of poets in the language who can be outrageously funny and serious in the same poem.” It is “honest, but by God, you have to read closely because often it is very reticent, very nimble and tongue-in-cheek.” The memoir was written in third person, with Whittemore referring to himself as “R,” which Harrison wrote “allows him to reveal doubts about himself and the role of a poet.”

Whittemore was born in New Haven, Conn., on Sept. 11, 1919, and graduated from Yale University in 1941. He and his roommate, James Angleton, started a literary magazine called Furioso, which published poets such as Ezra Pound and Williams Carlos Williams. At Yale, Whittemore began a friendship with English professor Arthur Mizener, which continued with correspondence through Whittemore’s service with the U.S. Army Air Force as a transportation and supply officer in England, North Africa and Italy during World War II. Whittemore’s first book of poetry, Heroes and Heroines, was published in 1946.

Yale University in 1941. He and his roommate, James Angleton, started a literary magazine called Furioso, which published poets such as Ezra Pound and Williams Carlos Williams. At Yale, Whittemore began a friendship with English professor Arthur Mizener, which continued with correspondence through Whittemore’s service with the U.S. Army Air Force as a transportation and supply officer in England, North Africa and Italy during World War II. Whittemore’s first book of poetry, Heroes and Heroines, was published in 1946.

Mizener had become head of the English Department at Carleton College in January of 1946 and Whittemore, who had started graduate work in history at Princeton but was unsure of this path, accepted the invitation of his mentor and friend to come to Northfield. (Mizener left for Cornell University in 1951, the year his best-selling biography of F. Scott Fitzgerald, A Far Side of Paradise, was published.)

Whittemore wrote that his life in Minnesota began in 1947 when he and two other new teachers, Gene and Hans, boarded with banker John Nutting and his wife Elizabeth at the mansion two blocks from campus, now used as the home of Carleton presidents. (Carleton archivist Eric Hillemann identified Gene as music professor Gene Bailey and “big and noisy” Hans as Joseph Rysan, assistant professor of German and Russian.) Hans, noticing that Whittemore owned a car, “concluded that car and person had appeared in his life in order to take him to Dundas.”

Why Dundas? Dundas had two bars and Northfield was dry. Whittemore wrote: “If some dutiful social scientist were to have wandered through the Midwest in mid-20th century looking for a representatively dull seedy backcountry burg he’d have settled for Dundas on the spot.” Hans and Whittemore “settled on it” two or three times a week for a little vodka and bourbon. This would lead Mizener to say to Whittemore in the presence of “other lofty English teachers and the Dean of Men” at a Carleton Tea Room lunch, “What did you booze hounds do for the world down in Dundas last night?”

Whittemore’s first class was Sophomore Lit on the second floor of Willis Hall. He described himself standing in front of “handsome and intelligent (mostly)” students who were “chatting and giggling,” and who stopped giggling and grabbed notebooks as soon as he started lecturing (and went overtime) about the French Revolution. Whittemore wrote, “First pedagogical lesson: a small class of intelligent gigglers is not a squad on a drill field.”

The second lesson the new teacher learned was “adjusting his new pedagogy to conversational classes rather than 50 minute lectures” and eventually Whittemore “began even to think that yes he could be a teacher for a year or two without losing his mind.” Of course, he still had to face grading 300-word papers “and if there ever was a course designed to make clear how hard it is to be a teacher at all, Freshman Comp was (and is) it.”

Whittemore wrote that he began liking the Midwest. The town of Northfield had important items on his wish list: “The list favored easy access to life’s necessities, and Northfield’s main street had a food store, a drug store, a doctors’ building, a clothing store, and a sedately uncomfortable hotel. Just off the main street it also had an old-fashioned movie house that showed at least one Jesse James film a year.” He also enjoyed the “relatively relaxed life” with his friends “over a pool table after a chatty lunch.” One unnerving thing for this Easterner: “the endlessness of the plains” in every direction beyond the town’s borders.

Whittemore revived Furioso in the spring of 1947. Said Whittemore: “Furioso took arms against the academic world, the new criticism, the writing world, the advertising world, General MacArthur, and the production of H-bombs.” He kept the magazine going through the spring of 1953, a total of 29 issues. Its ending afforded Whittemore more time to write poems, essays and reviews for major literary magazines.

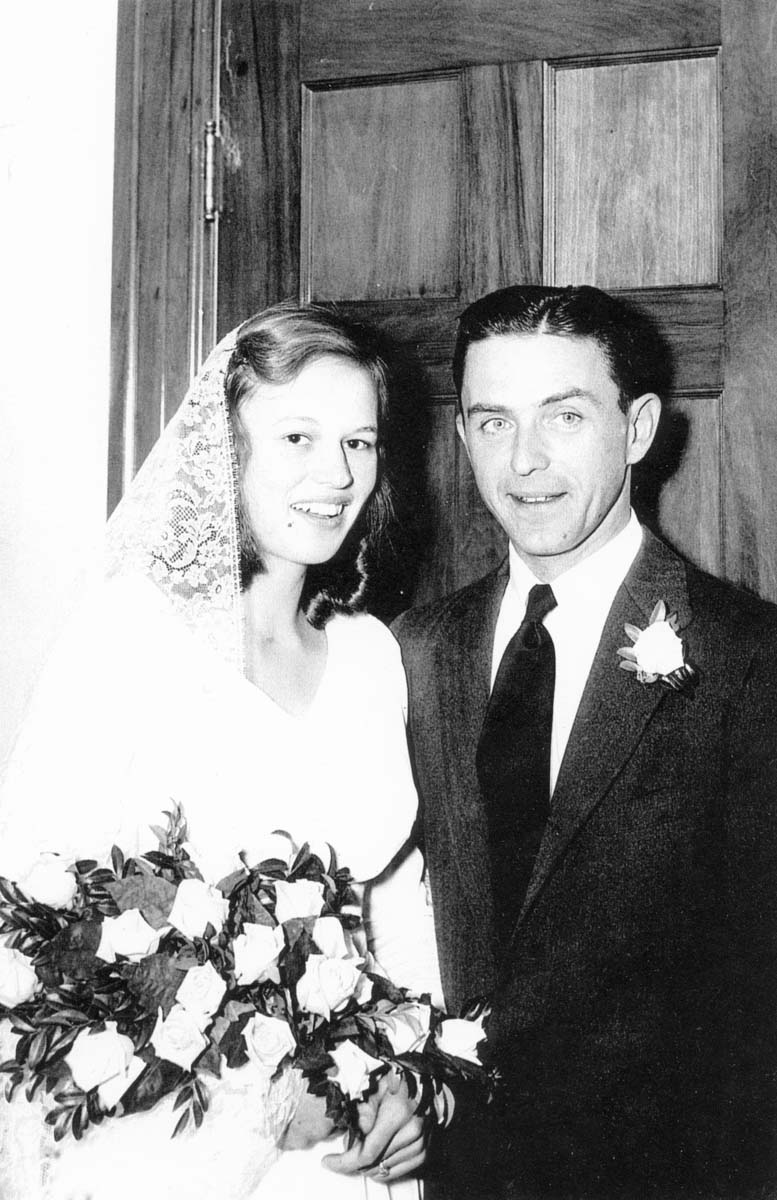

Early in 1952, Whittemore met Helen Lundeen, a Carleton student from Fergus Falls, at a student-faculty party. He wrote that she was 12 years younger, “more impulsive” and “thoroughly familied.” They married in October, lived in a farmhouse on the edge of Northfield and spent summers at Lundeen family cottages on Otter Tail Lake. Three of their four children were born in Northfield, Cate, Ned and Jack. (Daisy was born in 1967 in Washington, D.C.)

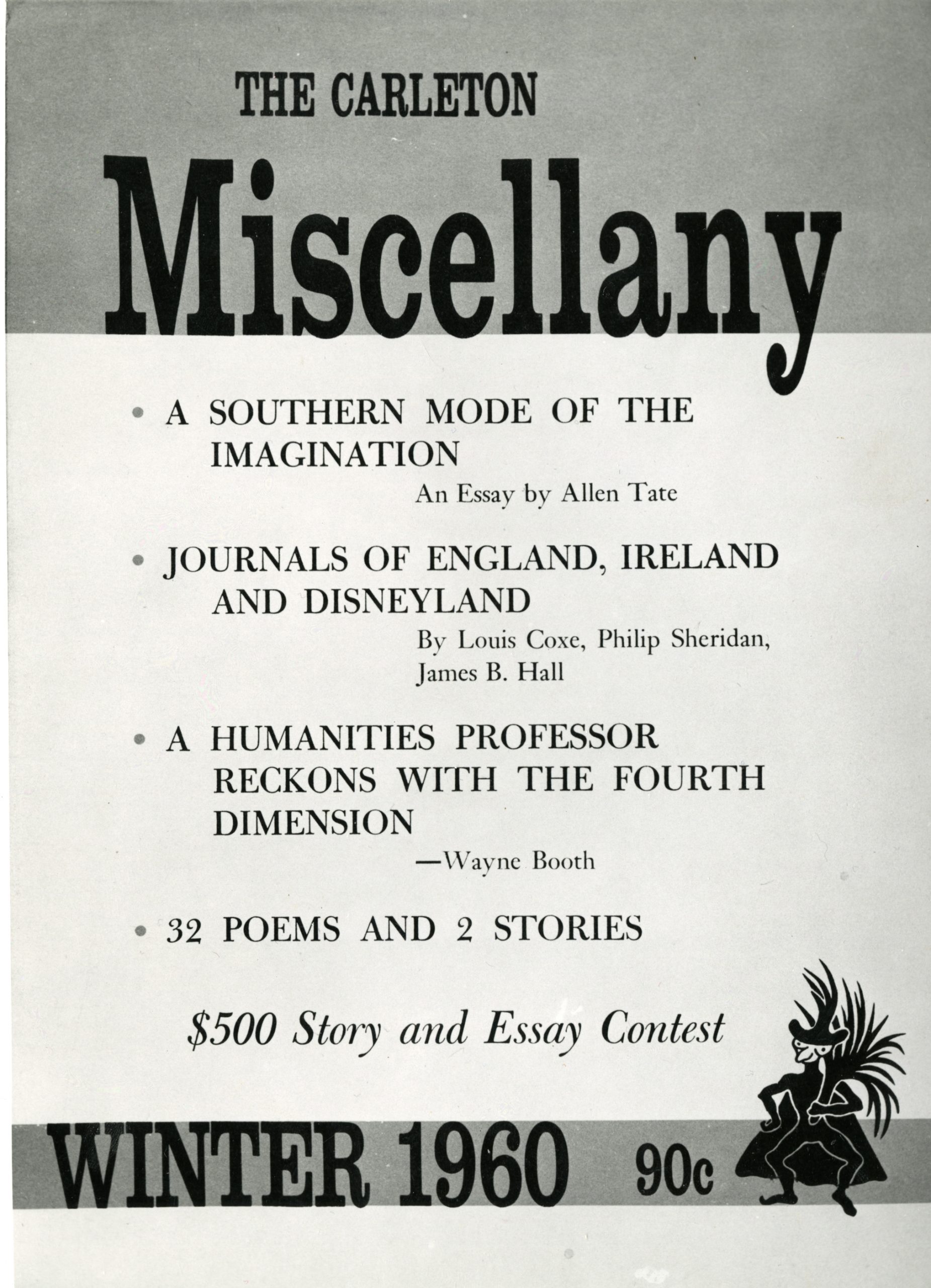

In January of 1960, a new literary magazine called the Carleton Miscellany was introduced. In the first issue, Whittemore wrote that the Miscellany would be “modeled in part” after Furioso, and the symbol of that magazine, “a sort of chimney sweep,” would be retained. Carleton English professors Wayne Carver and Erling Larsen worked as associate editors with Whittemore. (Carver told me that Carleton President Larry Gould was making plans to have such a literary magazine when Carver was recruited for the English Department in 1954 and Gould finally “got it off the ground” for Whittemore in 1960.)

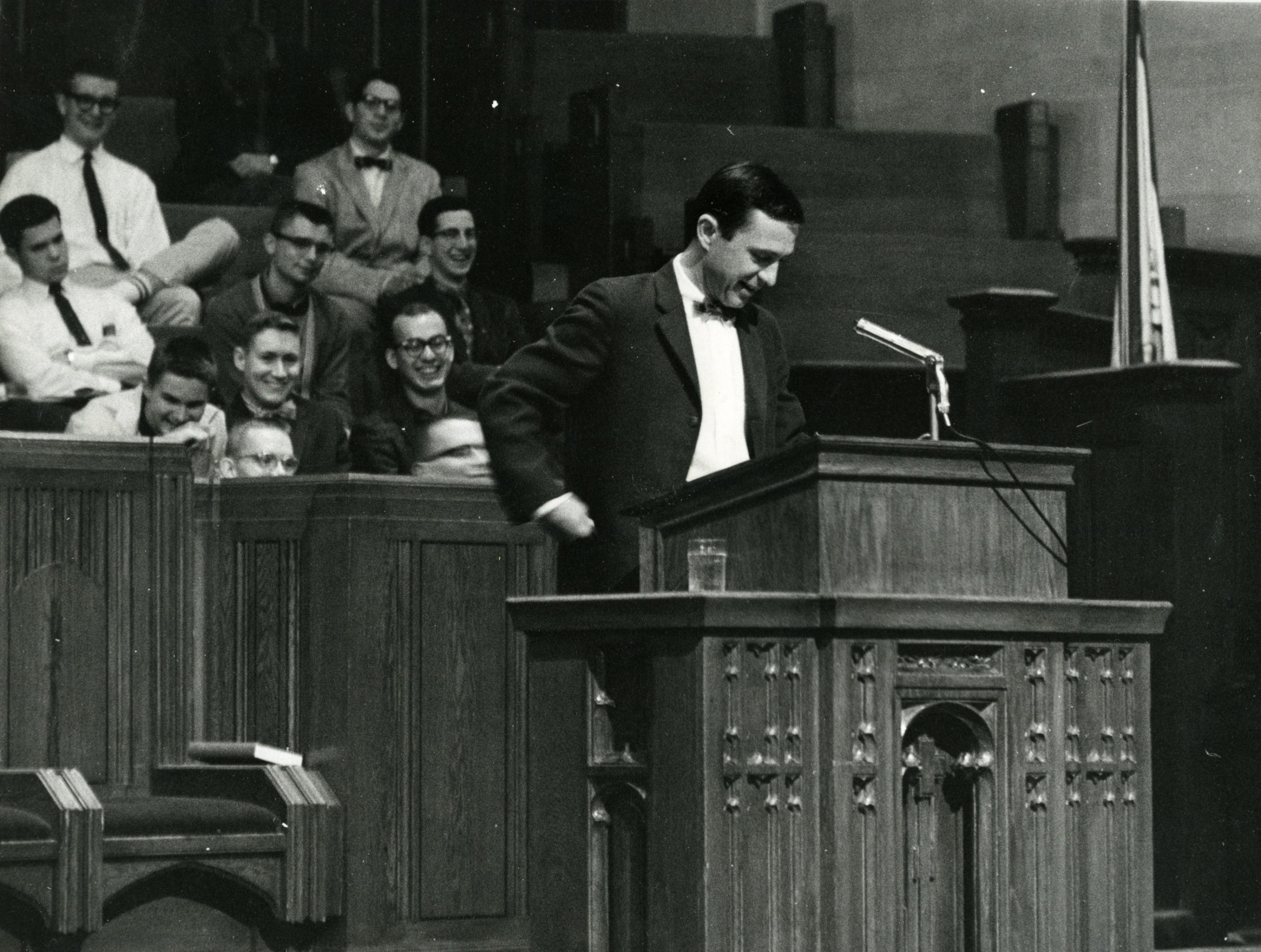

The first issue of 112 pages had two stories, poetry by 18 poets, essays, personal journals and other prose. It featured Whittemore’s Byronic epic in five cantos, “The Odyssey of a B**t,” which Whittemore had read to great applause at a college convocation in Skinner Memorial Chapel the preceding fall. The Minneapolis Sunday Tribune reviewed the first issue on Feb. 7, 1960: “There’s an element of mischief in it which sparks the scholarship and taste shown in the selection of contents,” due to editor Whittemore’s “uncivil tongue” and ability to “make his sentences and meters dance while thumbing a nose.” The conclusion: “The magazine is lively, literate and knowing, and deserves long life.” Robert Hatch, literary editor of The Nation, wrote, “I like your first issue; it’s good to be reassured that there are some professors around with a mental age of less than 75.”

Before its demise in 1980, the Carleton Miscellany published 1,944 works by 824 contributors, including 40 Carleton faculty and staff and many prominent literary figures. The list can be seen at apps.carleton.edu/digitalcollections/miscellany. Carolyn Soule was managing editor from 1963-80. The last Miscellany of Winter, 1980, was a “Ralph Ellison Festival.” Editor Keith Harrison wrote in this issue that the magazine had to “bow to other needs of the College” in “a time of budgetary constraint.” He added, “The withering dialectic of money must have its say.”

Before its demise in 1980, the Carleton Miscellany published 1,944 works by 824 contributors, including 40 Carleton faculty and staff and many prominent literary figures. The list can be seen at apps.carleton.edu/digitalcollections/miscellany. Carolyn Soule was managing editor from 1963-80. The last Miscellany of Winter, 1980, was a “Ralph Ellison Festival.” Editor Keith Harrison wrote in this issue that the magazine had to “bow to other needs of the College” in “a time of budgetary constraint.” He added, “The withering dialectic of money must have its say.”

In the fall of 1964, Whittemore began a sabbatical from Carleton as a consultant in poetry at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. There were only a few obligations, including introducing visiting poets, speaking to various groups and putting on a show twice a year. Whittemore wrote, “To have been hired to be largely idle for a whole year ($15,000 worth) was not a bad fate.” He told a Washington newspaper that he enjoyed the fascinating dinner-party conversations about politics and government.

Whittemore was welcomed warmly. The Washington Post wrote in October, “There’s a kook loose in the Library of Congress. He’s a lovely, lively, lilting, lyrical fellow who bears the somber pedagogical title of ‘Poet-in-Residence.’” Whittemore was said to have charmed a gathering with a poem about “the freshman fire that is held every year on a bald spot on the top of the hill at Carleton College in Northfield, Minn.” To the delight of those present, the poem ended with a rhyme of “gosh” and “frosh.” In other poems he read, Whittemore “impressed his audience with his sprightly sense of humor and eye-wide observance of the hum-drum daily things that go on in the world about him.”

The Whittemores returned for one more year in Northfield, living in a college-owned house on Nevada Street. In 1966, they moved back to Washington, D.C., where Whittemore worked at the National Institute of Public Affairs. He was a professor at the University of Maryland from 1967-84 and literary editor of the New Republic from 1969-73.

Whittemore came back to Carleton to give a Ward Lucas lecture in 1969 and returned again in 1971 to receive an honorary degree of doctor of letters. Former Carleton president Laurence Gould returned from Arizona to honor Whittemore, describing him as having “hammered from the tensions of his life both a literary life and life style that melds the music of driftwood with the lean dry agonies of skepticism.” He quoted Whittemore’s shortest poem, “It is not clear where we go from here/ Or, for that matter, who we’re.”

Whittemore’s poem, “The High School Band,” was one of four used by St. Olaf professor and composer Carolyn Jennings in her choral song cycle, “Sitting on the Porch,” which was premiered by the Northfield Chorale in 1987. The work was commissioned by the Northfield Arts Guild under a grant from the Composers Commissioning Program. Jennings told me, “The poets were all Minnesotans or (like Whittemore) had spent significant time in Minnesota. The work was scored for mixed chorus and piano.”

Whittemore took a two-week trip to the USSR in 1974, sponsored by the U.S. State Department and the Moscow Writers Union and had a trip to Israel in 1983, sponsored by USAID. In 1988 he launched yet another literary magazine Delos, which contained works translated from other languages.

In the publisher’s Afterword in Against the Grain, Merrill Leffler wrote that Whittemore had begun to notice problems with his memory as he was completing the first draft of this memoir. Subsequently, Whittemore was diagnosed with dementia and, at age 92, is now in a nursing home near Washington, D.C., where his wife still lives. Leffler e-mailed me that some of Whittemore’s memories are strong, “though which ones are unpredictable,” and that there are times when Whittemore has “strong glints of wit in a frail body.”

Current Northfield residents who were present during Whittemore’s time at Carleton shared some memories with me about those days. George Soule, a fiction editor for the Carleton Miscellany after Whittemore’s departure, was a student of Reed Whittemore as well as a Carleton faculty member with him for a couple years. Soule said, “He was my teacher for Shakespeare’s histories and comedies in the mid-50s and he was brilliant. I still trade off his insights.” Whittemore’s class “prepared me to read literature incisively better than any other course I took.” Bill Huyck, a classmate of Whittemore’s wife, Helen, and long-time Carleton track, hockey and cross country coach, remembered the Whittemores as the “center and motivators” of faculty social life, “friendly, informal, hospitable, generous and inclusive.” Huyck said Whittemore “never seemed egotistical or self-centered” and was “a remarkably accomplished and modest fellow.” Wayne Carver, who started the Carleton Miscellany with Whittemore and continued with it for 17 years, called Whittemore “the best editor I’ve ever seen.” Carver also said that with Whittemore’s Ivy League background, he had to make “strenuous efforts to become a Midwesterner.”

It was perhaps inevitable that Whittemore would leave Northfield to return to the East coast. But his influence still is felt in the lives he touched while here. Marc Reigel (Carleton Class of 1967) of Owatonna, now living in Columbus, Ohio, had Whittemore for a freshman rhetoric course. He said, “Although I was an 18-year-old student at Carleton in 1963, I recall that Mr. Whittemore taught us as though we were peers in the writing process.” Reigel, who went on to earn an advanced degree in American Literature, taught high school English and later worked as an independent education consultant on grant writing, feels that the inspiration of Whittemore shaped, informed and supported his work.

“I often used the metaphor of the ‘pebble and the pond’ with my students: throw a pebble in the pond and watch the ripples expand in concentric circles beyond the splash point,” said Reigel. “Nearly 50 years later, I can recall that a ‘pebble in the pond’ at a small college in Minnesota, Reed Whittemore, produced a ripple effect far beyond the initial ‘plink’ we teenagers perceived.”

My thanks to Eric Hillemann and Carol Thunem of the Carleton College Archives and to Merrill Leffler of Dryad Press for permission to use Whittemore’s poems (see www.dryadpress.com for information on ordering Whittemore’s memoir Against the Grain: The Literary Life of a Poet).

Poems by Reed Whittemore

The High School Band

by Reed Whittemore

On warm days in September the high school band

Is up with the birds and marches along our street,

Boom boom,

To a field where it goes boom boom until eight forty-five

When it marches, as in the old rhyme, back, boom boom,

To its study halls, leaving our street

Empty except for the leaves that descend to no drum

And lie still.

In September

A great many high school bands beat a great many drums,

And the silences after their partings are very deep.

A Teacher

by Reed Whittemore

“And gladly wolde he lerne, and gladly teche.” ((Chaucer))

He hated them all one by one but wanted to show them

What was Important and Vital and by God if

They thought they’d never have use for it he was

Sorry as hell for them, that’s all, with their genteel

Mercantile Main Street Babbitt

Bourgeois-barbaric faces, they were beyond

Saving, clearly, quite out of reach, and so he

G-rrr

Got up every morning and

G-rrr

Ate his breakfast and

G-rrr

Lumbered off to his eight o’clock

Gladly to teach.

Poems courtesy Dryad Press