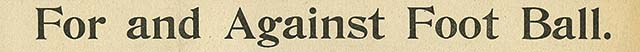

This was the giant headline in the Northfield News on Nov. 9, 1895, with the subhead, “Northfield College Presidents, Professors, Doctors and Citizens Express Their Opinions on The Game of Foot Ball as It is Played.” (Headline image courtesy of the Northfield Historical Society and Northfield News.) The article, which stretched over several pages, stated that the game had “taken hold of the lovers of out door sport this season right where base ball left off” and was also the subject of general discussion throughout the country. The newspaper’s position was that the rules of the game should be modified in the colleges where “brute force seems to reign” in a “maiming contest,” or else “the game should be prohibited.” When “rightly played for amusement and exercise,” rather than entered into with “fear and trembling,” it was “as good athletic sport as can be indulged in.”

Since it is November and since football has been much in the news again of late, I thought it would be a good time to look at attitudes toward “foot ball,” as it was once known, and to review the area’s early history of this game which has been both beloved and maligned over the years.

First, a few of the views from the 1895 account. Carleton’s president, J.W. Strong, said he was in sympathy with college athletics, which were supported at Carleton with both an instructor in Physical Culture and with a “fine athletic field” purchased recently. “Foot ball” was an “admirable method of developing alertness, self-reliance and courage, as well as strength of muscle and general physical vigor.” But Strong condemned “slugging match” games with aims to attain “brute victory at any cost.” In fact, he had seen such a game at Harvard, though “never as yet on Carleton grounds.” Anna T. Lincoln (who presided over dining tables at Carleton) said, “A man can afford an occasional black eye, a skinned or even broken nose, if foot ball playing makes the ear, the eye, the brain more active, alert and responsive, as it unquestionably does.” Carleton’s longtime Dean of Women Margaret Evans said, “Boisterous recreation” seems to be “carrying what might be beautiful sport into oft times brutal contests.” The game “helps to develop steadfastness, good soldiery, manhood, etc.” but, she said, “The greatest interest I take in the game is the learning of the news that Carleton is victorious.”

Northfield’s Mayor Norton declared, “There is not enough fun in it to pay for the risks that are run. It may be a manly game but I would not let a son of mine play the game and take the risks.” Dr. Dr. H. L. Cruttenden called it a ”genteel slugging match” which he did not approve of as played, “but as long as I am not the one to receive the aches and bruises I will not complain.”

St. Olaf College did not sanction football at this time and President Thorbjørn Mohn said strongly, “I have had enough of it. You can put me down for that. If the large educational institutions of this land wish to countenance this brutality – and I don’t think they will – every Christian citizen should set his foot upon it.” However, Mohn said he believed in outdoor sports and “the game, if modified, would be excellent.” But, “It seems awful to permit a game to be played at our colleges that endangers life and limb of students that are sent there to be educated and trained.”

The aforementioned “Physical Culture” instructor at Carleton was Max J. Exner, who gave his opinion that “foot ball” was “the only college sport which secures an all round symmetrical physical development, including harmonious development of heart and lungs.” Exner declared, “Physical injuries received are almost wholly temporary bruises. Foot ball has been played in Northfield for about six years, both at Carleton and in the High school. We do not know of a single individual who is in any way disabled as a result of playing the game.”

That same month of November, 1895, Edward W. Bok, editor of the Ladies Home Journal, had written that “by carefully-computed figures” (although he did not give the source), 46 deaths resulted in 1893 “from collegiate games of foot ball within a short period of four months.” He said, “No record has, of course, been kept of broken ears, lost vision and other disfigurements.” Football games differed only in degrees of brutality and were detriments to mental development of players. The so-called “fame” of the players was “directly injurious,” as players were exploited and spoiled with misplaced “preposterous and absurd” importance. He warned that other students would find it hard to pursue “a craving for knowledge” when all around them is “foot ball talk.” (It is an ironic fact that years later a technical high school in South Philadelphia was named after Bok and the Bok Wildcats team became a football powerhouse.)

Adverse reactions to the game continued, and on Nov. 23, 1897, the New York Times ran an editorial with the headline, “Two Curable Evils.” The first evil was the lynching of blacks. The second evil was what was called the time-wasting and brutal sport of football.

Let’s back up a bit here to origins of the game which provoked such a clamor. Football had its beginnings in the English games of soccer (aka the Association game, where a ball was kicked) and rugby (where the ball could be carried). Rutgers defeated Princeton in a game using soccer rules in 1869 and the game soon spread to Columbia, Cornell and Yale. Harvard adopted a rugby-soccer hybrid of kicking and running with the ball called the “Boston game.” In May of 1874, a rugby team from McGill University in Canada played two games at Harvard, first using Harvard rules (a game Harvard won 3-0) and then rugby (resulting in a scoreless tie). Harvard players and other eastern schools came to prefer rugby and it was a modified form of this game which spread to the Midwestern colleges.

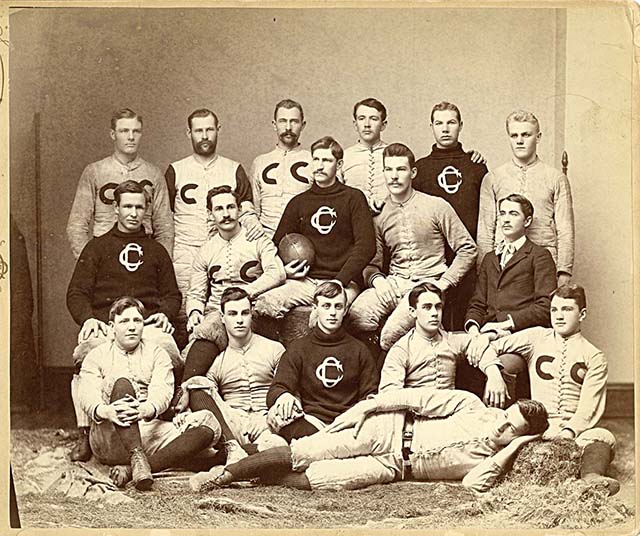

At Carleton College, which had been founded in 1866 as Northfield College and renamed Carleton after a benefactor in 1871, the first mention of the game is in the Carletonia in June of 1880: “Athletic sports do not flourish at Carleton. At the beginning of this term a football game was organized, but after a brief existence its little candle went out…Leapfrog was for all a time all the rage, but as warm weather came it too was voted too exhausting.”

A Dec. 16, 1899, article in the Northfield News said, “In October 1883 was played on the Carleton campus a peculiar game which may be said to mark a real beginning of the sport.” How was it peculiar? A team from the Univ. of Minn. came down to play rugby against a Carleton team which had been organized by a recent Carleton graduate, Selden Bacon, who had learned the game during two years at Yale. On the train, a professor who was accompanying the Minnesota team “learned what sort of a game the students had been playing and amazed them by the information that it was not Rugby.” The University men had been playing the Association game where the ball could be batted, thrown or kicked but could not be carried. Scoring was “by goals secured between the goal posts underneath the bar.”

So the question was, “How should two teams compete trained to totally diverse styles of play?” Carleton agreed to play the visitors’ Association style and, owing to “greater individual excellence” and “brilliant playing,” Carleton won four goals to two (at a time when touchdowns were worth two points) “against far greater average skill.” The University student newspaper wrote their football team “received a severe drubbing at the hands, or feet, rather, of the Northfield-Carleton Farmers Alliance Football Association.”

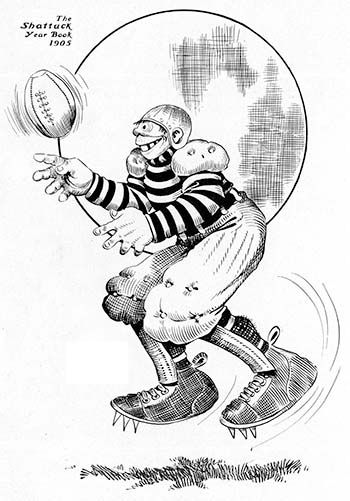

Buoyed by this success (and undeterred by having been called a “Farmers Alliance”!), another team was organized by Carleton in 1884, and played one game against Shattuck Military Academy in Faribault. Shattuck won 24-0. In 1888, Shattuck defeated Carleton 44-16. (A Shattuck yell went, “What makes Carleton play so slow? They are out of wind, you know!”) Also in 1888, the Carletonia said, “It is the general verdict of the girls that foot-ball has become a nuisance. People cannot cross the campus without danger of being hit by the ball.”

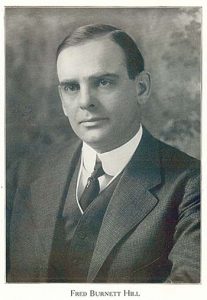

A history of Shattuck football in the 1905 yearbook found at the Rice County Historical Society in Faribault reveals that Shattuck pioneered the game before Minnesota, Wisconsin or Chicago took it up. In 1878, Charles C. Camp came from Yale to instruct at Shattuck, bringing “straight from the fountain head an expert knowledge of this glorious game.” (Camp’s brother Walter played and coached at Yale and is known as the father of American football.) Shattuck was “at a loss to find foemen worthy of her steel. During the eighties the State University was humbled year after year.” Just as Shattuck of today is known for fostering hockey stars, Shattuck trained many college varsity football players.

The first officially sanctioned Carleton football games were wins over Seabury Divinity School of Faribault, by scores of 14-6 and 4-0, in 1891. It was, however, the arrival of Max Exner at Carleton in the fall of 1892 to teach physical culture while earning a degree there which truly boosted the game. Exner came from the International Young Men’s Christian Association Training School in Springfield, Mass., where he had the distinction of playing on the football team led by the legendary coach Amos Alonzo Stagg and in the first ever “basket ball” game in 1891, devised by his roommate James Naismith.

The Carletonia of Oct. 29, 1892, commended Exner’s training of Carleton men who had “never played in a match game until this fall” and others who had never even seen a football game. Inexperience was not the only challenge. The article told of the Oct. 15 game played against Shattuck at Carleton when the Shattuck team brought along a referee who “seemed to be as determined to win the game for Shattuck as the Shads were themselves. He not only rendered his decisions in favor of the Shads at the bidding of the Shattuck captain, but even went so far as to block Carleton men in tackling and frequently cried out ‘Our ball.’ The final score stood 30 to 10 in favor of Shattuck.”

Despite such sins against good sportsmanship, the Algol yearbook of 1892-93 exulted: “There is no American college game which requires so much courage and pluck. No young man of brains and energy can afford to miss foot ball during his course if he would make of himself the best kind of a man, morally, intellectually and physically.”

According to longtime Carleton coach, Bob Sullivan, in Knights of the Gridiron: A History of Carleton Football 1883-2005, Carleton played 37 football games between 1883 and 1897, with a record of 22-14-1. Their 1898-1902 record was 25-13-2, including five losses to the Univ. of Minn.

After a game with the Univ. of Minn. in Oct. of 1896, the Minneapolis Times said, “The big Minnesota players were humiliated yesterday by the plucky little team from Carleton College by the score of 16-6.” Carleton lost this game. In 1897, Carleton again lost to the University 48-6 but Carleton rooters “danced themselves dizzy” after the lone score, celebrating a moral victory just because Carleton scored at all. This 1897 team then went on the road and upset the Univ. of N. Dak. in Grand Forks 20-0.

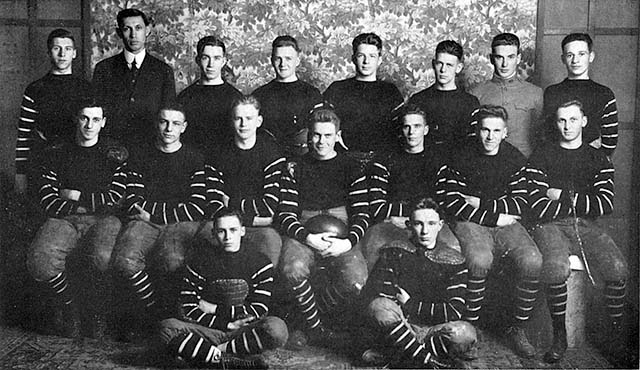

More football glory awaited. Between 1905 and 1917, the team recorded 66 wins, 17 losses and two ties, outscoring their opponents 1520 to 79. The team, under Coach C.J. Hunt, was undefeated from 1913-1916. Averaging more than 60 points a game in 1914, the team was not even scored against once in 1914 and 1915.

The climax came in October of 1916, with an achievement still written about in football history books. The Univ. of Chicago was at that time one of the most formidable college football powers, having already won four of the seven Big Ten championships which would be achieved under Amos Alonzo Stagg, who was the coach from 1892-1932. Carleton upset the heavily favored Univ. of Chicago 7-0 on Stagg Field in Chicago.

Northfield High School had its first football team in 1892 and was unbeaten in its first few years, including scoring 104 points against Faribault and having a victory over Carleton in 1894. (Games between local colleges and high school and prep schools ended in 1913.) On Oct. 8, 1898, Northfield played for the State Inter-High School football championship at Carleton’s field against Minneapolis South Side High School. The game ended in a scoreless tie.

Some St. Olaf students agitated for football at their school, too. The October, 1891, Manitou Messenger contained a “A Plea for Foot Ball,” in which the writer complained, “The goddess of base ball seems to have fascinated all, and her worshipers cling to her with a tenacity which allows them practically no time for foot ball.” The plea was for upperclassmen to “make a desperate attempt to introduce the most scientific, the most attractive, and the greatest of college games, football.”

The construction of a gymnasium in newly built Ytterboe Hall in 1900 increased pressure for athletics. But student petitions for intercollegiate football were regularly denied, probably because excesses in football had continued to inhibit the game itself. In their book, The Greatest Game: Football at St. Olaf College 1893-2003, Tom Porter and Bob Phelps explained, “Strategy and finesse played little or no part in the outcome of games: brute force, physical condition, and endurance were the determining factors. In 1905, the storm broke and football came close to destroying itself.”

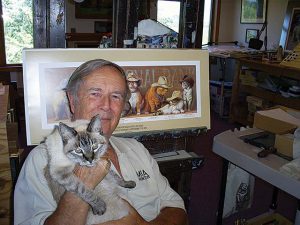

I spoke with Bob Sullivan about early football for Historic Happenings. Sullivan was head football coach at Carleton College from 1979-2000 and has been assisting his son, Bubba Sullivan, coaching the Northfield High School Raiders since 2003. I asked him what made turn of the century football so dangerous. For one thing, he said, there were plays where the ball carrier would be thrown, pulled or pushed forward, catapulted by bigger players, “to make sure he got the first down.” Then there were flying wedge plays where “They’d come down arm in arm and it was just power like a kickoff return, only it became part of all the plays, strictly a brute force thing, no finesse involved. Plus the equipment was so inferior at the time that injuries were bound to happen. The helmets were virtually paper and some guys didn’t want to wear them.” Sullivan could see why this “brute force” football, without finesse or art to it, was in danger of being outlawed.

Bruises and sprains, cracked bones and concussions were all part of the game, as happens today, but with players not required to wear helmets, face masks or shoulder pads, they were more prone to injury. The violence of the game was reflected in cheers, harmless sloganeering, but typical of the time. A 1905 Shattuck yell went, “Rickety, Rickety, X, Q, X,/ Break their necks, break their necks,/ Rush ‘em, crush ‘em, push ‘em through,/We are Shattuck, who are you?”

Activists inveighed against the sport, urging its abolition. Eighteen players had died playing football in 1905, with 159 seriously injured. Those were the grim statistics, amid growing public pressure, that led President Theodore Roosevelt to call representatives from Harvard, Yale and Princeton to the White House to discuss the situation on Oct. 9. Two larger conferences followed in New York in December and the Intercollegiate Athletic Association was organized (becoming the National Collegiate Athletic Association, NCAA, in 1910).

Among the rules made in 1906 to reshape the game were instituting penalties for unsportsmanlike conduct and unnecessary roughness, requiring ten yards (instead of five) in three plays for a first down (changed to four downs in 1912) and lining up with a neutral zone (line of scrimmage) to make officiating easier and thus cut down on brutality. (Sullivan told me, “The officials could now see if there was anybody eye-gouging or biting or doing any nasty stuff out there. It helped a lot to have a neutral area between the two teams instead of just right on top of each other.”) Also, the forward pass became a legal part of the game. The 1907 Shattuck yearbook noted that the 1906 team “tested out the possibilities of the hazardous forward pass” and used the “open style to good advantage” in a game against Carleton (which played “the old style, line plunging game”), but Shattuck lost “on a beautiful drop kick.”

Meanwhile, St. Olaf moved slowly toward intercollegiate competition. In its place, interclass football games were organized but lack of training and other factors made this an unsatisfactory substitute, especially when Oles looked across the river at the successes at Carleton. Finally, the faculty voted in October of 1917 to recommend intercollegiate football and on June 21, 1918, it was announced that intercollegiate football would be permitted at colleges of the Norwegian Lutheran Church.

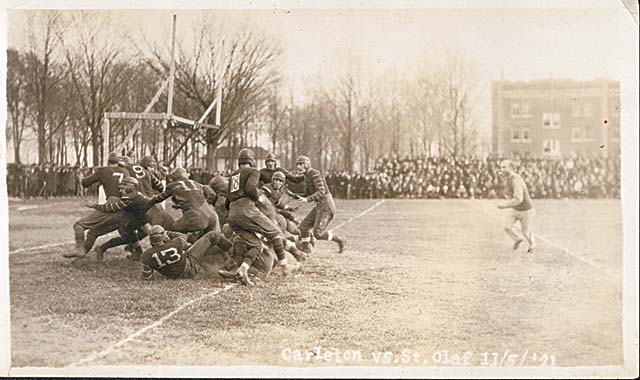

The first season of intercollegiate football at St. Olaf in the fall of 1918 brought about an unlikely pairing. Because of World War I, Carleton and St. Olaf had Student Army Training Corps units on campus which had to play together on a joint team, under Carleton’s coach Howard Buck. The first game, Oct. 19, was a 40-0 win over Pillsbury Academy of Owatonna, followed by a 59-6 drubbing by the University of Minnesota on Nov. 2. Spanish influenza led to the disbanding of the SATC team. The first St. Olaf team to play a full season in 1919 had a 2-3 record, including a loss to Carleton, 15 to 7.

The arguments for and against football continue these days, with some of the same sentiments expressed in 1895, despite advances made after college football faced possible abolition in 1905 due to charges of brutality. I am mostly “for” football. Through the 1909-19ll football seasons, my grandfather’s twin brother Reuben Rosenwald was an All-American halfback on the Univ. of Minn. championship teams. I’ve written about Minnesota’s only Heisman trophy winner, Bruce Smith of Faribault, and about Northfield High School’s 1997 state football championship. I have done extensive research on St. Olaf and Carleton College teams, including their metric football game in 1977 and the tradition of awarding a goat trophy in both football and basketball. I read the sports pages. So, I am a fan. But why?

I find myself coming back to what Carleton’s Dean of Women Margaret Evans said in her comments in the Nov. 9, 1895, Northfield News story, “For and Against Foot Ball”: “The greatest interest I take in the game is the learning of the news that Carleton is victorious.”

Except, since I am an Ole, change that to St. Olaf.

St. Olaf Face Mask in the College Football Hall of Fame

When the late Tom Porter (St. Olaf football coach from 1958-1990) was researching his 2005 book of St. Olaf College football history, The Greatest Game, he visited with Al Droen, a 1932 graduate who had played for St. Olaf. Droen told him that a face mask he had worn had been accepted by the College Football Hall of Fame in South Bend, Indiana.

Kent Stephens, historian and curator of the College Football Hall of Fame, now located in Atlanta, Georgia, confirmed that in Oct. of 1996, Droen had stopped by with this “personal artifact” he wished to share. Stephens said, “Due to injury he sustained, he created a metal face mask to protect himself from further injury. The face mask looked to be reminiscent of a phantom of the Opera mask. Inside the mask were the remnants of a leather pad that was riveted to the inside of the mask. His mask became one of our collection’s unique oddities and is exhibited frequently.”

Droen told Porter that on at least one occasion, “a game official denied him permission to play while wearing the mask.” In a Northfield News story of Nov. 20, 1931, Droen was described as a “great blocker and runner, and a fine low hurdler. He probably gets more fun out of hitting and being hit hard than any gridster in Northfield.” No doubt wearing that face mask helped.