Originally Published in the June 2014 Entertainment Guide

The late Dan Freeman (known as “Mr. Northfield”) had treasured memories from the times Doc Evans would come to town to play concerts for Evans’ alma mater, Carleton College. Evans, Class of 1929, was one of the most celebrated players and purveyors of traditional/Dixieland music. It was said that he could have gone longer without food than music. So, after the gigs, Evans would bring his cornet over to the Freeman house to have a jam session with locals, including Dan’s father Sid, a well-known clothier who was (according to Dan) “one of the very few Dixieland violinists.”

“Get upstairs!” Sid would say to Dan and his siblings but, “We’d come back down.” Dan told me that by the end of the evening 30 or 40 people would have gathered at his house to play and listen to music.

Carleton College hosted a centennial celebration Oct. 5-6, 2007, of the year of Paul Wesley Evans’ birth. Among those present was Eleanor Evans Hattery from Grand Marais, who had been married to Doc Evans from 1955 until his death in 1977.

This past fall, a year after the death of her second husband, Hattery moved to Northfield’s Village on the Cannon to be closer to two of her three sons and her grandchildren, thus becoming my neighbor and the inspiration for this June music issue column on the truly historic Doc Evans.

Evans, born June 20, 1907 in Spring Valley, Minnesota, was called “Doc” from an early age because of his love of reading. His father, a Methodist minister, died when Evans was only two years old, and Evans moved with his mother to West Concord, acquiring three stepbrothers when she remarried. Evans learned to play piano from an aunt and, remarkably, it was the only early music instruction he ever had. On his own, he took up drums and then saxophone in high school.

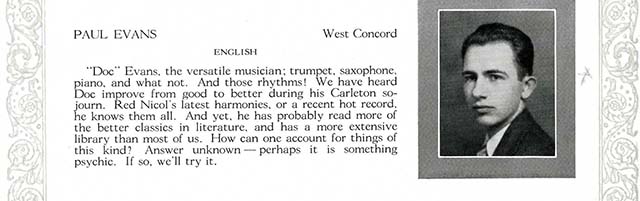

After graduating from West Concord High School in 1925, Evans enrolled at Carleton College where he was exposed to New Orleans jazz recordings. His musical versatility was especially appreciated as a member of the Carleton Collegians, which played for school dances and other events. He learned to play cornet and finally gave up the sax for this instrument.

Occasionally, Evans would pick up work in the Twin Cities, including with a nine-piece dance band led by Norvy Mulligan. In the spring of 1928, this band was hired to play Dixieland music at the Nankin Café. Evans described how, after riding the bus up to Minneapolis, he would have to take a bread truck back to Northfield, arriving early Monday morning in daylight. He would fall asleep in history class that day.

During the summer of 1928, Evans got more gigs in Minneapolis and stayed at the YMCA in Minneapolis. He was able to hear his idol, cornetist Bix Beiderbecke, perform with Paul Whiteman’s band at the Minnesota Theater. Evans, entranced, remembered how “the notes just sailed out and broke like bubbles over everyone’s head…”

Evans earned a B.A. in English at Carleton in 1929 and started graduate work at the Univ. of Minn., leaving to teach English, history, economics and business at West Concord High School until a budget cut eliminated that position. Evans said he “didn’t much care for the high school teaching, mainly because the students didn’t seem to care.” He was ready to make music his career, if he could. And he did, except for a sideline he started in 1936, which ran for about seven years: Evans raised cocker spaniels (including 11 champions) at Lane’s End Kennels on Wayzata Boulevard in Minneapolis.

Evans wrote about the 1930’s jazz and swing scene he was part of in a manuscript which was published in The Mississippi Rag of January, 1979, two years after his death. The entertainment industry was hit hard by the stock market crash of 1929. Dance bands were supposed to have a guaranteed minimum fee plus a percentage of the gate and, Evans wrote, “I can recall playing a one-nighter in St. Cloud, Minn., when my cut of the percentage (there was no guarantee) was 65¢.” The repeal of Prohibition in 1933 helped musicians pick up work, as saloons gave way to “lounges and cocktail bars” in Minnesota. (Evans wrote, “It is my considered opinion that often the distinction is academic.”) Evans recounted what happened when he worked in a Hennepin Avenue nightclub owned by an ex-bootlegger and the players were let go after a week without the two-week notice required by union rules. They were told “if any member went to the Union ‘the boys’ would take care of us. I’m afraid we didn’t quite have the courage of our convictions, and the band broke up then and there.”

Evans wrote, “As a business, dance orchestras and jazz bands really came into their own during the late ’30s.” With it came a revived interest in the New Orleans “hot” jazz, which Evans played. In 1939, jazz fan Herman Mitch opened a nightclub in Mendota, across the Minnesota River from Ft. Snelling, and Evans became the leader of a popular Dixieland band there until the club closed in 1942. Big names came to jam sessions at Mitch’s, including Duke Ellington, Fats Waller, Sophie Tucker, Jack Teagarden and Joe Sullivan. No fan of road trips and wanting to keep playing music his own way, Evans turned down all offers to leave.

Evans brought his band to Northfield on a regular basis in the post-war years. On Sept. 26, 1946, the Northfield News wrote that “a form of entertainment new in this part of the country” would be presented by Doc Evans and his band at the high school auditorium on Oct. 8. “Connoisseurs of hot jazz will be enthralled by the music of this group because it stems back to the early music of New Orleans as opposed to the wild and frantic swing music heard so often nowadays.”

Evans found a musical ally in John S. (Jax) Lucas, a 1941 graduate of Carleton. Lucas’ career as a jazz critic began when he wrote an adulatory story about Evans in 1945 for Downbeat magazine, calling Evans the successor to Bix Beiderbecke. Lucas made arrangements for Evans to make recordings for the Disc label as Doc Evans’ Dixieland Five in April of 1947 in New York. The band played classics of the Original Dixieland Jazz Band and New Orleans Rhythm Kings of the 1920s. Shortly thereafter, clarinetist Bill Reinhardt saw Evans perform at Chicago’s Hot Club and engaged Evans to lead a band at his new nightclub Jazz Limited. The club opened June 11, 1947, and Evans lived in Chicago for five years, playing at many Chicago hot spots, including the Beehive, Tailspin and Blue Note.

Lucas brought Evans to Northfield for a Feb. 15, 1949, performance at Carleton‘s Great Hall. Lucas taught English at Carleton from 1948 to 1958, sponsored the campus Jazz Club and often accompanied Evans on drums. During this visit, Evans recorded an album for the Art-Floral-Record Shop in town, part of a Joco “Jazz Heritage” series.

There are three entries of spinning 78 rpm records on YouTube which show Doc Evans’ mastery. They are marked “Joco Northfield Minnesota.” Norman Olsen, jazz enthusiast, owned and managed the Art-Floral-Record Shop at 411 Division St. S. (now the home of Fashion Fair). Olsen, a 1928 graduate of Northfield High School, began operating a remote studio in his store in Northfield in June of 1948 for KDHL radio in Faribault and, by August of 1949, he was broadcasting three programs, including one on Friday evenings called “A Session for Mouldy Figs” (a term for a person who likes Dixieland jazz). Also in 1949, he began manufacturing Joco records, all by Doc Evans and his Dixieland Band. Distributors were located all over the U.S. and abroad. Recordings were made at St. Olaf studios and Schmitt’s in Minneapolis and other Joco “Jazz Heritage Albums” followed. These 78 rpm recordings were considered Evans’ finest work to date.

Evans once said, “I’d never have made it if I hadn’t got out of town.” But, in the fall of 1952, having been helped by the Windy City to attain a national reputation, Evans returned from Chicago to the Twin Cities for good. Hattery told me the reason he came back was simple: “This was his home.”

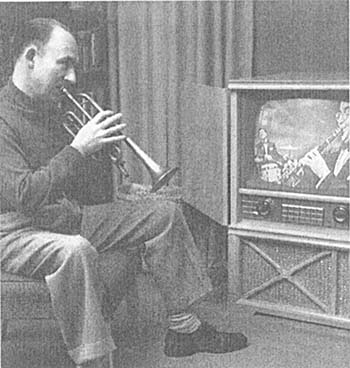

It did not take long for Evans to get back into the Minnesota swing of things. Evans assembled a band and played everywhere. (“Jazz doesn’t know where it is and doesn’t care,” Evans once said.) He toured the upper Midwest in a Univ. of Minn. Concert and Lecture Series. Hattery said, “His mission in life was really to recreate the old jazz and he felt very strongly about that. In fact, he loved to do concerts where he could do a little bit of history of jazz along with it, explaining who wrote the piece and information about it.”

A Downbeat story by Will Jones on Nov. 18, 1953, was headlined, “Doc Evans Finally Rates as a Hometown Hero.” The story: “Suddenly it’s most fashionable to be a Doc Evans fan in the Twin Cities. And since Minneapolis is home to Evans, he couldn’t be happier. He never liked the idea of leaving home to go to Chicago or New York to make a buck at the thing he knows best.” The story highlighted a most successful series called “Doc Evans Dixieland Concerts” held that past summer at the Walker Art Center courtyard, which attracted overflow audiences. Hattery called this series “phenomenal,” with guest performers and themes. Evans shared his knowledge and talents in this way for eight years.

On April 10, 1954, Evans celebrated the 25th anniversary of his Carleton graduation with a concert at a packed Great Hall. Accompanying Doc on cornet were Knocky Parker on piano and Lucas on drums. This concert was recorded as Classic Jazz at Carleton by Soma Recording Company of Minneapolis.

Eleanor Pumper met her future husband late in 1954. A native of S. Minneapolis and a graduate of South High, she had met Evans’ drummer, Red Maddock, at a La Crosse, Wisconsin, performance while she was attending Winona State College. Two years later, after working a 3:30 to midnight shift at Snyder’s Drugstore in Minneapolis, she was walking with friends down Hennepin Avenue and heard “this wonderful music coming out of Williams Bar and we went in.” She recognized Maddock and “he recognized me or at least he pretended to, and I was later introduced to Doc. I went back there a few times and then he asked me out.”

records featuring Doc Evans and his band under the Joco label. They were said to be Evans’ finest work to date. Record courtesy of Chip DeMann.

Despite the disparity in their ages, romance bloomed quickly. She “liked the fact that he had been a teacher, a lecturer, I liked his music and his looks. He had a wonderful personality.” They were married July 18, 1955. (Their rings were purchased in Northfield at the jewelry story of Evans’ friend, Cort Lippert.) The couple lived in Bloomington, with a cabin in Grand Marais, just off the Gunflint Trail, and had three sons, Jeff, Allan and Mark. Hattery told me Evans was a very good family man, “interested in having them all play an instrument.” Jeff played violin, Allan played trumpet and Mark viola. The home was filled with collections of all sorts of music.

In July of 1958, Evans opened his own nightclub in Mendota called the Rampart Street Club, with only Dixieland music allowed. There was a sign, “Please do not mention modern jazz when people are eating!” The club closed in December of 1961. The month before, on Nov. 12, Doc Evans played with a traditional jazz trio at a Northfield Arts Guild event, which also featured a progressive jazz trio of Carleton students, including Northfield native Peter Basquin on piano. After separate sets, the trios combined to prove “traditional and modern jazzmen do have some things in common,” according to the Northfield News. Hattery thinks this might be the only time Evans appeared on a bill with modern jazz.

During spring breaks of 1964 to 1966, Hattery accompanied her husband to Daytona Beach where a flatbed truck of Dixieland musicians would play while young Christian athletes would try to convert sun worshippers to worship of a different kind. Evans was quoted in a Minneapolis Star article on April 16, 1966, as saying, “Kids today aren’t bad, but they are often inconsiderate. We try and make them think about morality, and get them to be aware of and concerned about other people.”

April 10, 1954. Soma Records recorded this concert as

Classic Jazz at Carleton, featuring Doc Evans, Knocky

Parker on piano and Jax Lucas from the Carleton English Dept. on drums. Over the years, Evans recorded 36 LPs. Photo courtesy of Carleton College Archives.

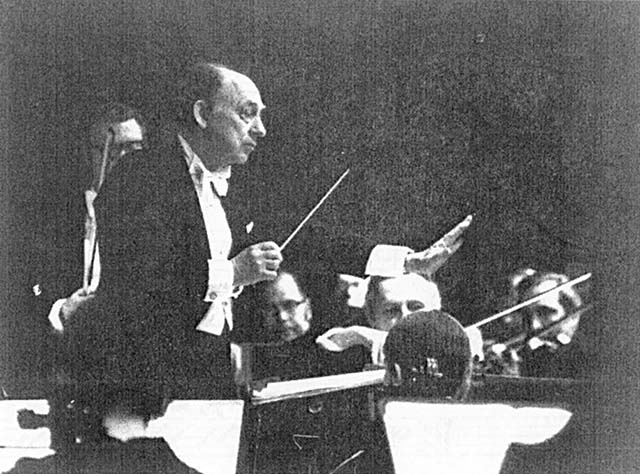

Evans had always been a classical music fan and, Hattery told me, he “wanted to write some classical music for string quartets. He thought it would be a much better idea if he learned to play an instrument that you use in a string quartet.” So Evans said to her, “As long as I’m learning to play, you might as well come along and learn, too.” So they took cello lessons together.

Hattery said that Evans also “wanted the experience of leading an orchestra,“ and in 1963, Evans founded the Bloomington Symphony and conducted it until his death in 1977. In this orchestra, his wife played cello and son Jeff played violin.

Evans was invited to a 70th birthday celebration in Los Angeles for the inimitable Louis Armstrong. The New York Times of July 5, 1970, reported that trumpeters Clark Terry and Doc Evans were among the performers playing to a crowd of 6,700 for three hours on July 3 at the Shrine Auditorium. There was a seven-tier, 12-foot-high birthday cake in honor of “Satchmo.” Hattery said that Evans was very honored to be invited and that Armstrong told Evans, “You sure do know how to play that horn!”

In 1972, Evans was honored with an Alumni Achievement Award from Carleton. By this time, he had also received awards of merit for his service to music from Minneapolis, St. Paul and Bloomington. In 1976, Evans was named the first Bicentennial Distinguished Citizen of Bloomington and Feb. 16 was declared “Doc Evans Day” in Bloomington.

Evans suffered from asthma, which gave him breathing problems and sometimes led him to switch from cornet to trumpet or play piano with his bands. Evans’ death on the bitterly cold day of Jan. 10, 1977, was swift and unexpected. Evans had left a meeting of the Minneapolis Musicians Association (of which he was an officer) and was found dead in his car at age 69, of a heart attack perhaps triggered by an asthmatic attack.

Evans’ son, Allan, recalled that Evans had arranged W.C. Handy’s St. Louis Blues for his high school jazz band, which they were rehearsing when Evans died. Allan Evans played a trumpet solo at the spring concert and wrote, “I am still amazed to this day that I played it without a hitch.” Allan Evans maintains a website for his father, docevans.com, and organized an annual Doc Evans Jazz Festival, which was held in Albert Lea from July of 1999 to 2008. He said, “My father, Doc Evans, was a kind, gentle family man who could play the cornet better than almost anyone.”

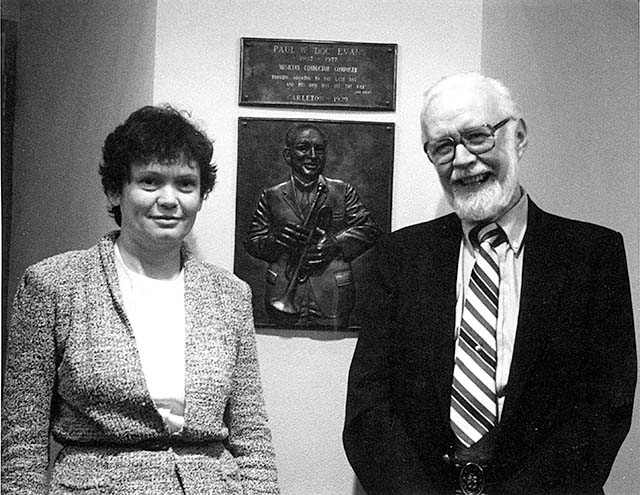

Doc Evans’ wife Eleanor is shown at Carleton College on Nov. 18, 1981, with sculptor Ray Gormley of Prior Lake who created the bronze plaque commissioned in Evans’ memory after his death in 1977. Photo courtesy of Carleton College Archives.

Then, on Oct. 5-6, 2007, Carleton honored Evans again, this time in the centennial year of his birth. The event was organized by Stephen Kelly. A Doc Evans Centennial Memorial Band was formed, directed by Butch Thompson who had played with Evans and is known for his long association with Garrison Keillor’s A Prairie Home Companion. This band played for a convocation and concert on Oct. 5. The next day, a symposium and a panel discussion were held.

Perhaps it is fitting to close with Lucas’ words inscribed on the bronze plaque which memorializes Evans at Carleton:

DOC EVANS (1907-1977)

Blowing growing to the last day and his own man all the way.

Thanks to Carleton archivist Eric Hillemann and Eleanor Evans Hattery for their assistance with this story. Also thanks to Mark Randolph Flaherty, whose 2002 University of Minnesota doctoral thesis on The Life and Music of Paul Wesley “Doc” Evans (1907-1977) is now part of the Carleton College Archives. See the website maintained by Evans’ son, Allan Evans, at docevans.com for further information, aimed at keeping Doc Evans’ legacy alive.