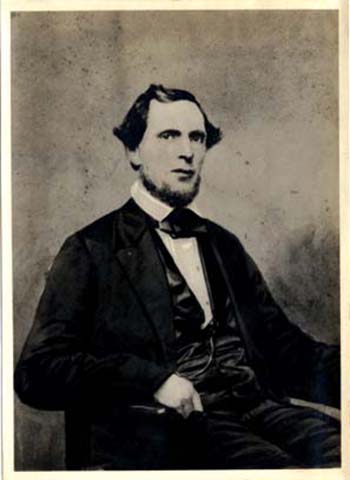

A clause inserted into every deed of land by Northfield’s founder John North was “No intoxicating drinks shall be sold or in any manner furnished as a beverage on said premises.” North, an attorney from New York, had helped found both the Minnesota Republican Party and the University of Minnesota during the years he had lived in St. Anthony and was well known as a temperance advocate. After buying one quarter of an interest in Faribault, he talked of moving there until he heard another owner, Alexander Faribault, was not averse to a drink or two. So when North decided to develop a mill site north of Faribault on the Cannon River in 1855, soon to be called Northfield, he wanted to make sure settlers were of like mind with him about liquor.

However, not everyone was on board with this idea. On Feb. 14, 1858, Ann North wrote her parents in New York about a series of evening meetings at the schoolhouse for all denominations. She said there are “some who are believed to be hopefully converted, and among them is Mr. Kimball, whose liquors were so unceremoniously spilled, a few weeks ago.”

This reference to Kimball is related to an incident which came out of John North’s temperance policies. In the summer of 1857, Benjamin Kimball had built a hotel called the “Mansion House” on the west side of town just out of the jurisdiction of North, according to Edward Neill’s 1882 History of Rice County. When Kimball later opened a bar in the hotel, within a few weeks three men (named in Neill’s account as Ann’s brother George Loomis, W.W. Willis and Warren Weed) appeared and “with an ax demolished barrels and bottles; this literally broke up the establishment, and it was never reopened. Of course this breaking of the peace created considerable excitement, but the man was paid a small sum for his loss.”

In the course of research for a book I wrote for the Northfield Historical Society about Northfield’s oldest building, the Lyceum, a story was found in Faribault’s Rice County Herald from Nov. 26, 1857, which seemed to indicate this violent event was not unexpected. The writer noted that Northfield was “established on a temperance basis” with no intoxicating drinks sold within its limits: “But just previous to the late election, a doggery [a cheap saloon] was planted just over the river, on the school section. It served its patrons gloriously on that day, and the citizens now have determined its destruction. We hope their resolution may be executed.” As indeed it was, a few months later.

In addition, I located an undated, unsigned letter to Mr. Kimball at the Northfield Public Library in a scrapbook about Northfield (compiled by Mrs. Charles A. Bierman, the town’s unofficial historian in the early 20th century). The letter reads:

Mr. Kimball, The businesses of Northfield and vicinity do hereby protest against the sale of intoxicating liquors in this place, believing that no language can express the suffering which it has always been the lot of woman to endure as a direct consequence of such sale. In commencing this business in this place you have arrayed yourself in direct hostility to our dearest interests as the object of a liquor shop is to make drunkards of our dearest friends – our neighbors – our now innocent children to create an atmosphere of vice and immorality which must inevitably taint with moral poison the rising generation. We therefore protest against the business and request an immediate abandonment of the traffic.

So the threat to Northfield’s “dry” status was forcibly removed, although “moral poison” was available not far away. A writer in the Nov. 26, 1857, Rice County Herald bemoaned the fact that his town of Faribault did not have a literary association like Northfield’s Lyceum “where all classes may spend a pleasant and profitable hour, without being compelled to resort to one of the many gambling and drinking houses which are disgracing and ruining our else delightful town.”

Another discovery in the scrapbook in the Northfield Library is a brief essay titled, “Total Abstainers.” The unnamed writer declared:

It is highly absurd to call drunkenness a “beastly habit.” Who ever heard talk of a beast that was addicted to drunkenness? It would be altogether too bad to libel the lower animals after this fashion. They are all, without exception, members of the temperance society, and very strict ones, too; for their abstinence is not confined to ardent spirits, but extends to wine, malt liquor, and every other intoxicating agent. Epicures some of them may be, and other gluttons, but not one of the whole lot can be charged with sacrificing at the shrine of Bacchus. It follows then, that total abstinence from all intoxicating drinks is supported by animal instinct, as well as by sound reason – that of all brutes, the tippler is the most brutish – and, that of all beasts, the drunkard is the most beastly.

John North attracted early settlers to Northfield who shared his dedication to education, abolition and temperance throughout his years here (1855-61). In 1870, North founded the town of Riverside, California, and in the summer of 1879, surprising rumors reached Northfield from the west coast. On Aug. 27, 1879, North wrote a letter to C.A. Wheaton, editor of the Rice County Journal, saying, “And so the accusation this time is that I have ‘taken to drinking.’ It is gratifying to know that the people of Northfield are still interested in me – so much to feel sad at any calamity that may befall me.” During his years of “severe ordeals,” he said he had used stimulants prescribed by a physician and was “thus spared to my family.” He wrote, “This is better for them and me than to have sacrificed myself to the extreme notions of some who are shocked at the idea of using stimulants even as medicine.”

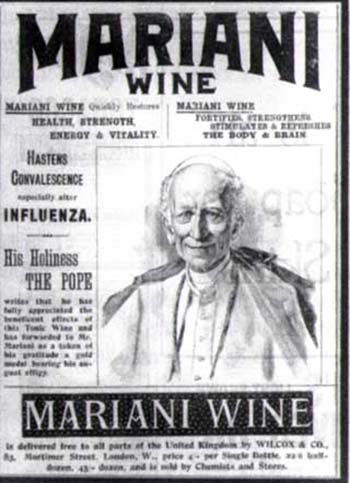

It appears that by the late 1890s, Northfielders were coming around to North’s approval of liquor for medicinal purposes. Local newspapers prominently displayed ads for Vin Mariani, a wine described as “salvation for Overworked Men, Delicate Women, Sickly Children” which was recommended by “more than 8,000 American Physicians” for “Nervous Troubles, Throat and Lung Diseases, Dyspepsia, Consumption, General Debility, Malaria, Wasting Diseases and La Grippe.” Pope Leo even sent a gold medal to Angelo Mariani, the Corsican originator of the this tonic with its touch of palliative cocaine. Pope Leo said he had been supported in his “ascetic retirement” by a flask of wine which was “never empty.” Another popular advertised medicinal remedy was Pabst Malt Extract which “causes sweet sleep, restores faded looks, lightens weary minds and builds up the body,” giving you “vim and bounce.”

The United States entered the era of prohibition in 1919, introduced by Minnesota Congressman Andrew Volstead of Kenyon. North’s daughter, Mary North Shepard, wrote from California in 1929 to Carl Weicht, editor of the Northfield News, that although her father’s views on liquor modified as he grew older, he “never favored social drinking and, next to woman suffrage, I can think of no act of our government over which he would have so rejoiced as over the Volstead Act.” It is an interesting side note that Volstead attended St. Olaf College, which still has an official policy banning the possession or use of alcohol on campus. This policy is said to reflect the college’s “commitment to healthy life styles.”

Prohibition ended in 1933. And in this issue of the Northfield Entertainment Guide, readers can vote on their favorite place to imbibe. Our town founder might not approve but the ghost of Benjamin Kimball, whose liquors were so “unceremoniously spilled” early in 1858, may feel vindicated.

Susan Hvistendahl’s book, The Lyceum: Northfield’s Oldest Building, is available for purchase at the Northfield Historical Society, 408 Division St. S. The book is the second in the NHS History Series.