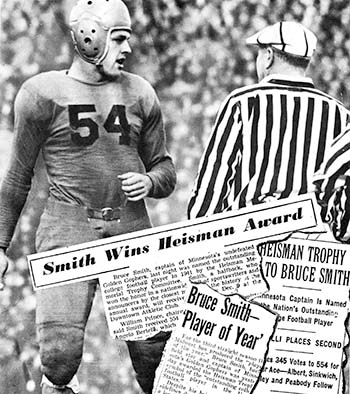

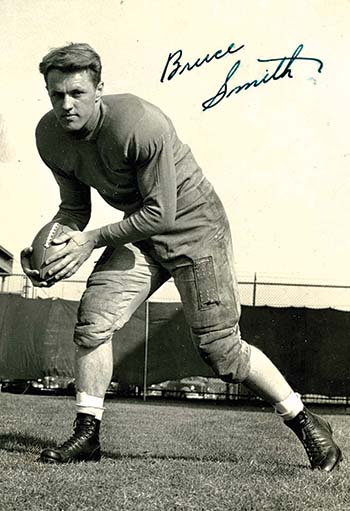

If you are living in Faribault, you probably have heard the name Bruce Smith. As in: Bruce Smith Memorial Field, the Bruce Smith Golf Classic, a Bruce Smith exhibit at the Rice County Historical Society. If you are a hard-core football fan, you may know Smith as the football hero from Faribault High’s class of 1938 who went on to help the University of Minnesota win back-to-back national championships in 1940 and 1941 and was the only Minnesota football player to ever win the Heisman Trophy as the most outstanding college player of 1941.

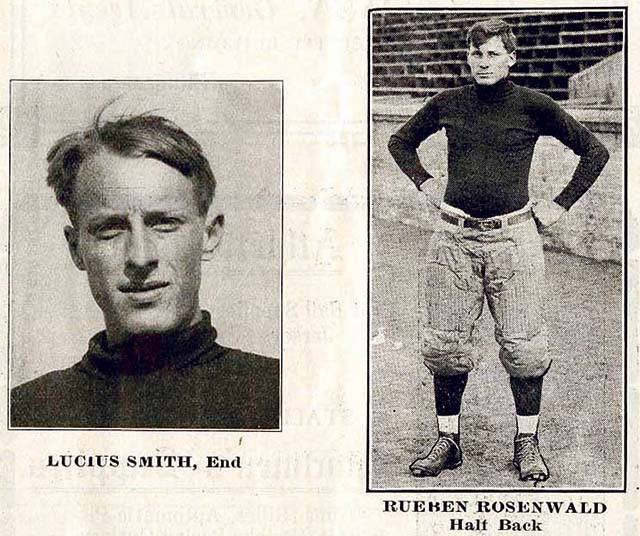

One oft-told tale is that Bruce Smith’s father, Lucius Smith, a longtime Faribault attorney who had played for the Golden Gophers in 1910 and 1911, groomed his son to avenge a 6-0 loss at arch-rival Michigan on Nov. 19, 1910, which had spoiled an undefeated season. In the 1972 book Gold Glory by Richard Rainbolt, Lucius Smith said, “I felt because of my inexperience at tackle, I was partly responsible for the loss to Michigan. Someone said I had made the statement that someday I would have a boy who would show up Michigan. I never even thought such a thing, but the myth grew.”

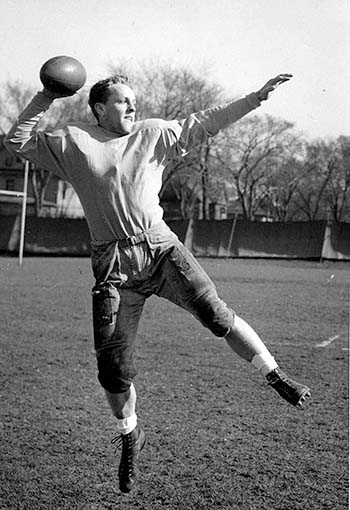

Even without this revenge theme, the game Bruce Smith played on Nov. 9, 1940, for the undefeated Gophers against undefeated Michigan before a home crowd of 64,000 at Memorial Stadium was the stuff of legends. Bruce Smith considered it “definitely the high mark of my football career.” It was a stormy day with a sloppy field. Michigan was leading 6-0 towards the end of the first half and had recovered a blocked punt inside the Minnesota five-yard line. But a Gopher interception in the end zone gave the ball back to Minnesota at the 20. The speedy halfback Smith got the ball on a reverse and took off for a spectacular 80-yard touchdown run, considered one of the best TDs in Gopher history. The successful point after won the game, as there was no scoring in the second half.

The next year in Ann Arbor, the Gophers won again, 7-0, with team captain Smith setting up the only score with a pass. Despite a knee injury which kept Smith out of the next two games against Northwestern and Nebraska, Minnesota entered the game against Iowa with a 6-0 record. Head coach Bernie Bierman yielded to Smith’s pleas to go into the game when Minnesota was unable to move the ball in the first quarter. Incredibly, Smith then accounted for all the Gopher scoring as he ran or passed for five touchdowns in a 34-13 win. The Gophers then wrapped up the season with a 41-6 victory over Wisconsin and their second national title in a row. Coach Bierman said that Smith was “a completely unselfish, dedicated team player. He could do it all – a brilliant runner, a deadly tackler, a devastating blocker, an excellent passer and a good kicker.” It was no wonder that Smith was awarded the Heisman Trophy in 1941. Nevertheless, when he found out he had won the Heisman, his characteristically modest comment was, “I have to pinch myself every five minutes. I can’t believe it’s true. There are hundreds of other guys who deserve it – not me.”

Within the voluminous files on Bruce Smith at the Rice County Historical Society, I found a letter from Lucius and an essay by Bruce to be particularly illuminating about his upbringing and the kind of athlete – and person – that he was.

On Aug. 25, 1941, before Bruce’s senior year as a Gopher, his proud father, Lucius, wrote a letter to Gordon Gammack of the Des Moines Register and Tribune in response to a request for information about this emerging star. Lucius said that Bruce was born on Feb. 8, 1920, into a Faribault family of Irish, Scottish and Scandinavian roots. Lucius’ own parents had refused written permission for him to play football in Faribault, but Lucius practiced punting and dropkicking on his own and carried this over when he and his wife Emma started their own family of five children.

Lucius wrote: “Kicking, passing and tackling practice has been going on in (and I mean in) and around our home since the oldest boy was five years old…We passed, drop-kicked and tackled in the yard and living room to the despair of the rest of the family and the destruction of chandeliers and furniture.”

Lucius noted that Bruce had won more than a dozen letters, playing football all through high school (with All-State honors in 1937 and 1938) and having been on the golf and basketball teams since 8th grade. Bruce was high point man his last two years, taking his basketball team as far as the state tournament his senior year. All this in spite of bouts with pneumonia and even a broken leg. Bruce won the American Legion award for athletic and scholastic excellence and continued with excellent marks at the university.

Lucius gave this insight into his son’s philosophy: “He is happier over a perfect block than a touchdown run. His idea is that the blocker is working for the team, while the ball-carrier has the team working for him. The man who can’t gain with ten good men helping him had better let someone else try. After running 80 yards against Michigan last fall, he maintained that with the blocking he had his sister, June, could have done as well.”

(Or perhaps better. Lucius also wrote of June: “No local boy of her age can outdo her at running, kicking and passing, and she is a vicious tackler.”)

At the age of 16, Bruce wrote about himself for a high school speech class (grade: B+). He described himself as weighing 175 pounds, with blue eyes and light brown hair. Then: “I think a small town of this size is a better place for a boy to grow up in than a large city. I have lived in a clean, pleasant and respectable home and have associated with people having the same characteristics.” He recalled his earliest experiences with football in Garfield Grade School: “As I remember it these football games were about 10 percent football and 50 percent arguments and 40 percent fights.” (He had also been a proud member of Miss Ann Anderson’s Garfield Drum Corps.) The current year, he wrote, would be filled with studies, football, basketball and just a “little” dancing. He said that he had been “too bashful to go to a dance,“ but at a “leap year dance” (girl asks boy) last winter, “I learned that even ‘trying’ to dance was an enjoyable pastime.” (Bruce was also a self-taught boogie-woogie piano player of some repute and loved to draw, hunt, fish and study birds.)

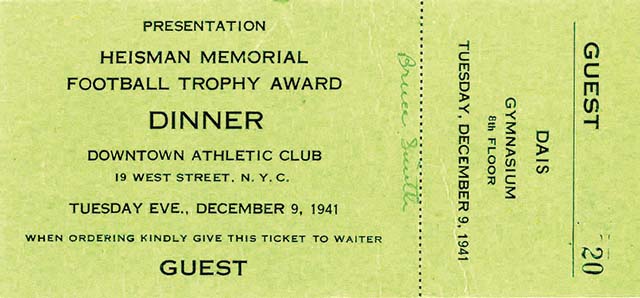

Dec. 9, 1941, two days after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, which necessitated a revision of Bruce Smith’s planned remarks. All images courtesy of the Rice County Historical Society Collection

Now, at the age of 21, this modest young man had been awarded the Heisman Trophy as the best college football player of the year, as decided by 554 sports writers and radio commentators. He was on his way by train to New York City’s Downtown Athletic Club for the presentation, after stopping off in Chicago to accept another prestigious award (the Eversharp), and was readying his speech for the audience of 900. But history intervened to change the content when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, just two days before the Heisman ceremony. On Dec. 9, Smith found his Heisman acceptance speech was to precede further word to the nation on the radio from President F.D. Roosevelt about the “date which will live in infamy.”

Smith said, “So much of emotional significance has happened in such a brief space of time, that the task of responding on this occasion leaves me at a loss to assign relative values.” Smith accepted the trophy on behalf of his teammates and “the greatest coach of all time, Bernie Bierman.” Smith then declared, “Those Far Eastern fellows may think that American boys are soft, but I have had and even now have plenty of evidence in black and blue to show that they are making a big mistake. I think that America will owe a great debt to the game of football when we finish this thing off. It keeps millions of American youngsters like myself hard and able to take it, and come back for more, both from a physical standpoint and that of morale. It teaches team play and cooperation, and eggs us on to go out and fight hard for the honor of our school and, likewise, that same spirit can be depended on when we have to fight like blazes to defend our country.”

Not long after this, Columbia Pictures called on the photogenic and athletic young man to appear in the movie, Smith of Minnesota. The plot concerns a skeptical screenwriter who comes to the small town of Faribault to see if the All-American, Heisman-winning Smith (playing himself) is as virtuous as advertised. (Spoiler alert: He is.) While filming took place in California, actual game footage from Minnesota’s Memorial Stadium was edited in.

By the time of the movie’s debut in Sept. of 1942, Smith had won the MVP Award that summer in the College All-Star game against the Chicago Bears and was a flier with the U.S. Navy. He also spent some time playing offense and defense for the Great Lakes Naval Station in Chicago and then for St. Mary’s Flight School in California.

Smith went on to play with the Green Bay Packers, mostly on defense, from 1945 to 1948, then briefly for the Los Angeles Rams. Injuries slowed him down. Lucius Smith remembered vividly what happened at a game between Green Bay and the Chicago Bears in 1947: “It was a brawl. I saw Bruce get kicked in the back. He was removed on a stretcher and taken to a hospital. They said he had a ruptured kidney and might die.” Bruce recovered but ended up retiring at the age of 29.

Smith had teamed up to start a business in Northfield in 1947 with his hometown friend Gib Dapper, who was also a Navy veteran and had been a football star at St. Thomas. By now, Smith had married a fashion model, Gloria Bardeau, whom he had met during the service. (They went on to have a family of four children, Bonnie, Barbara, Bruce and Scott.) The Smith and Dapper Sporting Goods Store replaced the Crary Bookstore in the Freeman Building at 411 Division St. in Northfield (current location of Fashion Fair). Northfield clothier Sid Freeman wrote in 1971 that during Smith’s time in Northfield (which had ended by 1953), Smith had coached kids’ teams and had given sports equipment “at cost or free,” while also helping out with Carleton’s football team, without pay. Freeman also commended Smith’s subsequent work as a salesman for After Six Men’s Formal Wear.

Smith’s last job was as a Hamm’s beer distributor in Alexandria, Minnesota. He died of cancer on Aug. 28, 1967, at the age of 47, and was interred in Veteran’s National Cemetery at Ft. Snelling. Sid Freeman was among the pall bearers at his funeral.

Smith’s wife, Gloria, wrote a poignant letter about her husband when Smith was being considered for the College Football Hall of Fame. She said they were married for years before Bruce let her see Smith of Minnesota on television. She then wrote, “It is too bad that a movie could not be made on his tremendous courage, during the illness that finally his strength could not overcome” because “that is the true Bruce Smith Story and the test of one man’s greatness, for that far surpasses his feats on the football field.” Smith “lived three months longer than any medical explanation on sheer determination. He wanted to be home, where he could hear the boys playing basketball, and watch the kids water skiing from our porch off the bedroom. He wanted everyone to have as normal a summer as possible.” When Gloria would mention a possible miracle, he would say, “I’m having my miracle, I will have the summer with my family.” And he did, wrote Gloria. “I learned to give him shots, and tried not to let it show on my face when he dwindled from 235 down to 90 pounds. He knew if he ever broke down, I would fall apart, so I guess it was the game of pretend, but that’s the way we played it.”

Despite his illness, the deeply religious Smith had accompanied a priest, Rev. William J. Cantwell, on hospital rounds, helping to encourage young cancer patients. Though at first unfamiliar with Smith’s football career, Cantwell was impressed by Smith’s devotion to service throughout his physical trials and, 11 years after Smith’s death, nominated Smith for sainthood in the Roman Catholic Church.

It did not take long for Smith’s hometown to honor him. On Oct. 17, 1968, the Faribault High School Athletic Field was dedicated as Bruce Smith Memorial Field. And supporters near and far started a movement to get Smith into the College Football Hall of Fame, including Univ. of Michigan star Tom Harmon. Harmon affirmed on Sept. 27, 1971, that Smith “did indeed live and practice the ideals we all expect of an All-American,” and “deserves this accolade as much as anyone I have ever played with or against.” (Harmon, who won the Heisman Trophy himself in 1940 and had already been elected to the Hall of Fame, is the late father of today’s NCIS television star, Mark Harmon.) Minnesota Gov. Wendell Anderson declared Oct. 14, 1972, as Bruce Smith Day, the day Smith was honored at halftime of the Purdue-Minnesota game for his induction. Then, in 1977, Smith’s number 54 became the first Univ. of Minn. number to be retired from the roster.

Another Bruce Smith Day was proclaimed by Gov. Mark Dayton for Sept. 17, 2011. It was the 70th anniversary year of Smith’s Heisman triumph and a celebration was planned for TCF Bank Stadium at the game the Gophers played against Miami University (Ohio). Faribault fans had been active in promoting this recognition and “Bruce Smith Week” was declared by the city. A contingent of 50 fans made the trek to Minneapolis to salute the hometown hero, as did Smith family members. Scenes of Smith’s career flashed by on the video screens and trading cards about Smith were distributed. At the end of the first quarter, internationally known wood carver Ivan Whillock of Faribault presented a bronze bust of Smith to be placed in the Gopher Hall of Fame display. (The bust was financed by individuals and businesses in Faribault, led by committee members Bruce Krinke and David Henry. Whillock donated another bronze bust to Faribault High School.)

Also in 2011 the rediscovery of the audio of Smith’s historic Heisman speech at RCHS led to its use in a nine-minute documentary about Smith by Julie Fox of Fox Video Productions and Bruce Krinke of Faribault Community Television. The audio became part of an eight-minute “Outside the Lines” segment on Smith on ESPN which first aired on Nov. 6 and included commentary from RCHS Executive Director Susan Garwood and Smith’s sons. Garwood tells me that Bruce Smith’s name is still in the top five inquiries at the historical society.

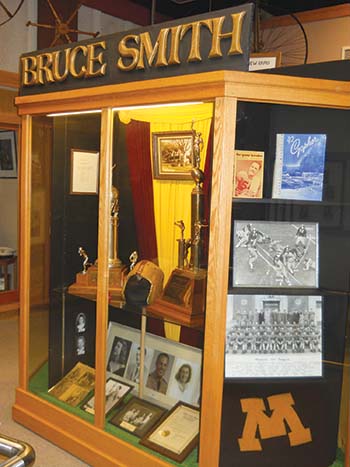

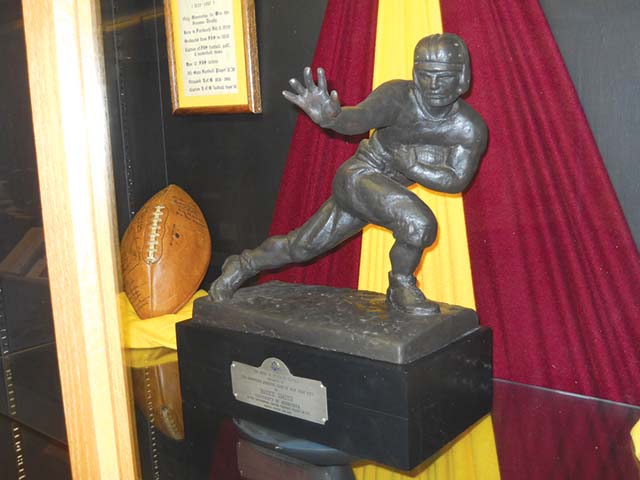

The Bruce Smith Memorial Display case, with many family donated items, is widely viewed at the society. Among the memorabilia in this display, which was funded by the Faribault Jaycees in 1981, is a rare replica of Smith’s Heisman Trophy. It was the persistence of former board president and long-time volunteer member Beverly Nauman that finally led to permission from the Downtown Athletic Club for a replica to be made with the understanding that it “would remain on display and never be sold.” (The cost to RCHS was $1200.)

And what of the original Heisman Trophy that Smith won? The Dec. 21, 2005, Echo Press of Alexandria reported that “After 20 bids, another Heisman Trophy was sold. It is believed to be the fifth one to go on the auction block.” The price was nearly $400,000, the “highest amount paid for any Heisman trophy.” At 82, Smith’s widow, Gloria, had said it was time to part with it, along with other memorabilia.

The Heisman was bought by Los Angeles businessman, Gary Cypres (an owner of travel and mortgage companies). Cypres had wanted to place the trophy in a special exhibit within a 27,000-square-foot museum he was creating. However, it seems that things did not work out for Cypres as he had planned.

The Heisman was bought by Los Angeles businessman, Gary Cypres (an owner of travel and mortgage companies). Cypres had wanted to place the trophy in a special exhibit within a 27,000-square-foot museum he was creating. However, it seems that things did not work out for Cypres as he had planned.

Cypres’ gigantic Sports Museum of Los Angeles opened in his warehouse south of downtown L.A. in November of 2008 with 30 galleries and a collection of 10,000 items valued at more than $30 million. In addition to Bruce Smith’s Heisman, Cypres had many objects connected to athletes like Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig and Joe DiMaggio, and to teams, mostly from his native New York and from California. (One prize was the famed T206 Honus Wagner baseball card.) Within three months, the Sports Museum had closed due to lack of patrons, attributed to the economy and location of the museum. It has since been open only for special events, such as a premiere of the movie 42 about Jackie Robinson.

A New York Times story on Aug. 7, 2013, related how Cypres came of age in the Bronx and started collecting during New York’s Golden Age of baseball of the Yankees, Giants and Dodgers, 1947-57. Today, nearing 70, Cypres is “hoping to find someone with the means and the belief in its significance and value” to keep his collection together and validate what he calls the “idiotic,” “little boy’s choice” he had made to house his collection in Los Angeles rather than to rent out his warehouse.

So, while the fate of Bruce Smith’s Heisman Trophy may be undetermined, you can see the replica of it at the Rice County Historical Society, 1814 N.W. 2nd Ave. in Faribault and reflect on the remarkable life and legacy of Bruce Smith of Minnesota.

Thanks to Susan Garwood, Executive Director of the Rice County Historical Society, for her assistance with this story.