If you are a visitor to Northfield for this year’s Defeat of Jesse James Days, Sept. 9-13, you can perhaps be forgiven if you call it “Jesse James Days” and leave off “Defeat of.” However, Northfield residents should school themselves never to do so because the annual event (first held in 1948) celebrates the action of townspeople on Sept. 7, 1876, when the cry, “Get your guns, boys, they’re robbing the bank!” rallied the citizens to defeat the infamous James-Younger Gang of outlaws.

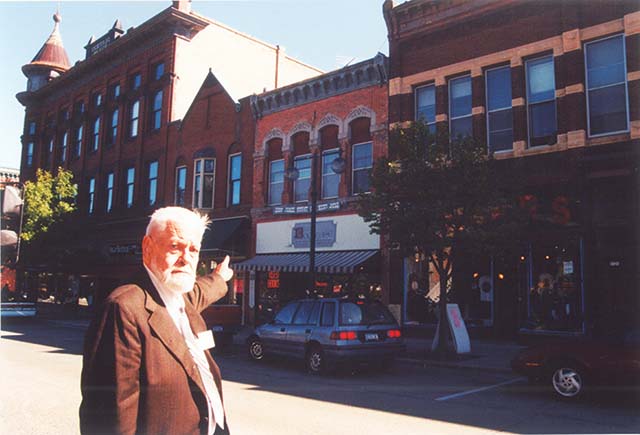

The location of the raid was the First National Bank, current site of the Northfield Historical Society in the Scriver Building at 408 Division St. Hayes Scriven, executive director of the Northfield Historical Society, is looking forward to a new emphasis on the response of the town in the exhibit area of the museum which focuses on the robbery. A big boost to that aim came in November of 2014 when Norman Oberto of Northfield purchased the Henry Wheeler collection from the previous owner in North Dakota and loaned it for permanent display at the museum. The new display, which opened June 16, contains the Smith carbine Wheeler used to kill outlaw Clell Miller and wound Bob Younger, the gold watch First National Bank gave Wheeler for his actions and a small pistol Wheeler carried for the rest of his life. (See below for interview with Oberto and Scriven.)

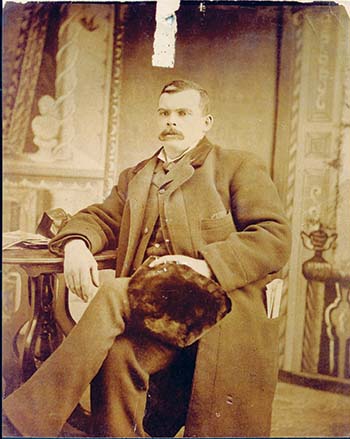

So just who was Henry Wheeler? He was a hero of the bank raid, of course, but a man of many other accomplishments, as I found out in my research.

Henry Mason Wheeler was born in Newport, New Hampshire, on June 23, 1854, but grew up in the young town of Northfield (founded by John W. North in 1855) when he moved here with his parents, Mason and Huldah Wheeler, at the age of two. He graduated from Carleton College’s Preparatory Department in June of 1873 and began the study of medicine under local Northfield doctor Charles M. Thompson, who had received a medical degree from the Univ. of Michigan. Wheeler was 22 years old and had completed his first year of medical school at the University of Michigan when the James-Younger Gang rode into town, intent on robbing the First National Bank.

Here is the account (with some explication in brackets) that Wheeler wrote for the 50th anniversary of the raid, a carbon copy of which is found at the Northfield Historical Society and which was printed in the Northfield News of Sept. 10, 1926.

“At the time of the Northfield bank raid, Thursday, Sept. 7, 1876, I was a student in medicine and home in Northfield for my holidays. I was sitting on the sidewalk, in front of father’s drug store, nearly opposite the bank about half past one or two in the afternoon, when I saw three men ride up the street, tie their horses, and go into the bank. I thought they were cattlemen… [Then] two more men came riding up the street, and stopped in front of the bank. One of them dismounted, looked in thru the bank door, and then remained outside. I was beginning to get suspicious, rose from my chair and moved up the street until I was directly opposite the bank. J.S. Allen approached the bank and attempted to enter, but received a blow from the horseman which sent him spinning down the street.

“I shouted, ‘Robbery! They are robbing the bank,’ with the result that the man in front of the bank turned immediately and fired at me, but the shot went over my head. ‘Get back, or I’ll kill you,’ he shouted. [Hardware merchant J.S. Allen reportedly cried, “Get your guns, boys, they’re robbing the bank!”]

“I ran into the drug store, thinking to get my gun, which I generally kept there, but I had lent it to someone who had returned it to the house. I made for the Dampier hotel, where I knew there was a gun, running thru the alley to keep out of sight of the bandit, picked up the gun, asked the clerk for ammunition, and he got me four cartridges from the storeroom.

“I ran upstairs to a bedroom on the third floor [which was the second floor of the hotel itself], facing the bank. As I approached the window, three more men on horseback came riding up across the bridge square, shooting. I shot at one of them [Jim Younger], but missed him. I reloaded. The man who had fired at me before had got into the saddle and was bending down adjusting the left stirrup. I got a rest for the gun in a corner of the window, aimed low and shot him [Clell Miller] thru the chest.

“In the meantime, A.R. Manning had come up to the corner on the other side of the street, shot one of the horses, behind which some of the bandits were sheltering themselves, and had also shot one of the men [Bill Chadwell]. Bob Younger had come out of the bank and was having a revolver duel with Manning. I took a shot at Bob, breaking his right elbow. My fourth cartridge had fallen from the bed to the floor, breaking the tissue paper forming the cartridge, and the powder had escaped, so my ammunition was exhausted. I watched two bandits come out of the bank, mount their horses, and ride away with the others. At this time the clerk came with more cartridges for me, but he was too late.

“When the excitement had died down, it was found that the robbers had made away with about $290 [that early estimate turned out to be only $26.70], which they took from the till on the counter, but Heywood had refused to open the safe, declaring there was a time lock on it, which he could not open. They shot him [Joseph Lee Heywood, acting cashier] thru the head, killing him instantly, but were afraid to go into the vault.”

At first, townspeople thought the shooting might be publicity for a wild west show. By coincidence, Henry Wheeler’s future wife, Addie Murray, was at the dental office of D. J. Whiting at the top of outside stairs of the Scriver Building. When they came out to the landing to see what was happening, they dodged a bullet and quickly retreated.

A posse was formed to chase after the outlaws and Wheeler joined in, leaving instructions to his friends and fellow University of Michigan medical students, Clarence Persons and Charles Dampier (son of Edward Dampier, the owner of both the hotel and the gun Wheeler used) to try to get the bodies of the two dead outlaws as cadavers for their school. The oft-told story is that the students were given tacit permission to do so because the bodies would be buried in a shallow grave. Accordingly, the bodies were dug up from Northfield Cemetery, put in barrels marked paint and shipped to Ann Arbor.

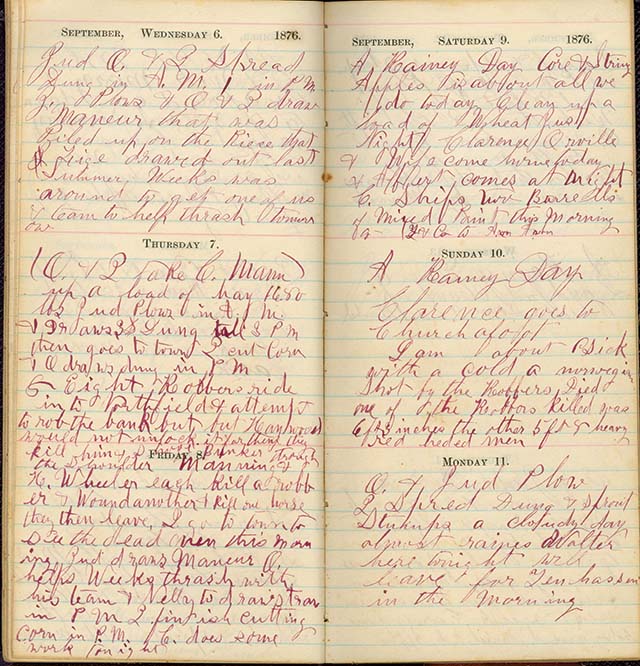

A diary of Clarence Person’s brother, Newton, in the Northfield Historical Society archives seems to support this story. The Sept. 7, 1876, entry takes note of the robbery, then Sept. 8 says, “C. [Clarence] does some work tonight” and Sept. 9 records that “C. ships two barrels of mixed paint this morning to…Ann Arbor.” There are also accounts that when Wheeler returned to Ann Arbor and was asked by a student about how he got one of the cadavers, Wheeler replied, “I shot him” (at which point, some sources say the interrogator fainted and/or dropped out of school.) At any rate, the Ann Arbor Courier reported, “The students of the medical department will this winter have the pleasure of carving up two genuine robbers, being members of the Northfield, Minnesota, gang.” But Miller’s indignant brother Edward showed up in Michigan and was given a corpse to bury in Missouri which may not have been clearly identifiable. There is speculation that Wheeler may have kept the remains of Miller or Chadwell after graduation, since he had a skeleton in his office in North Dakota. (See below for further adventures of the deceased outlaws.)

Wheeler obtained his medical degree at the University of Michigan in 1877. The Northfield Mail of Oct. 16, 1878, reported the Oct. 9 wedding at the Congregational Church of the “highly esteemed and respected” Dr. H.M. Wheeler and Adeline Murray (his high school sweetheart), who have “grown up here among us” and “have a warm place in the hearts of our people.” The story concluded, “We acknowledge a liberal supply of cake.” The Rice County Journal story of Oct. 17 said, “We wish the happy young couple a long, happy, and prosperous life, and that no clouds may ever darken their horizon; not even the most partial eclipse of the honeymoon.” In September of 1879, Dr. Wheeler left for New York to attend the College of Physicians and Surgeons, finished work in 1880 and practiced medicine in Northfield.

On June 23, 1881, the Rice County Journal wrote of an unimaginable tragedy: the death of the infant daughter of the Wheelers “after the brief stay of one day in this world” and the death the next day of Addie, after only two years and eight months of marriage. The story said, “Mrs. Wheeler was one of our loveliest young women, but the seeds of that fell destroyer consumption, lingered in her system, till about six months ago it developed itself in an acute form of throat disease, which rapidly hastened the termination of her earthly career.” The mother and daughter were buried in one coffin in Northfield’s Oaklawn Cemetery. The newspaper said, “This is a stunning blow to the young husband, as well as to the grief stricken family of the departed” who have “heartfelt sympathy of a wide circle of friends.”

The very next month, Wheeler left for Grand Forks, Dakota Territory, to set up a pioneering practice as a prominent physician and surgeon. According to John Koblas in Faithful Unto Death (Northfield Historical Society Press, 2001), Wheeler “dedicated much of his medical life to improvement of obstetrical procedures.” Wheeler married a St. Cloud schoolteacher, Josephine E. Connell, in 1883 and the couple constructed a brick Italianate house inspired by the home of his friend, the railroad tycoon, James J. Hill, with whom he often went hunting. Wheeler was surgeon for Hills’ Great Northern and Northern Pacific railroads and, in 1886, he was the first dean of the new Medical School at the University of North Dakota at Grand Forks.

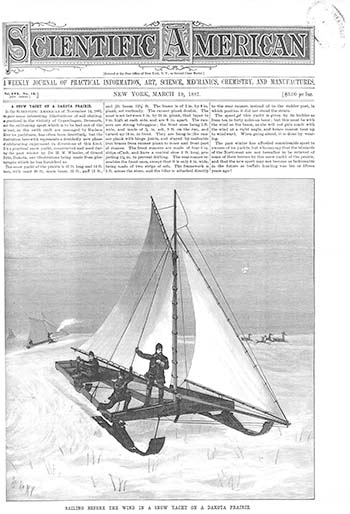

On March 19, 1887, an invention of Wheeler appeared on the front page of the prestigious Scientific American of New York (“a weekly journal of practical information, art, science, mechanics, chemistry, and manufactures”), along with an illustration labeled “Sailing Before the Wind in a Snow Yacht on a Dakota Prairie.” Wheeler’s 32-foot long snow yacht was said to be “a decidedly new phase of exhilarating enjoyment in diversions of this kind” which could reach speeds of from ten to 40 miles an hour. The journal speculated that the new sport might “become as fashionable in the future as buffalo hunting was 10 or 15 years ago.”

In 1895, Wheeler became president of the North Dakota Medical Association that he had helped to found. Not surprisingly, he helped to organize the Grand Forks Gun Club, too, and was president in 1897.

On Oct. 23, 1897, the Grand Forks Herald had some fun at the expense of the popular doctor with this item: “Doctor Wheeler is in danger of losing his reputation as a marksman and received many condolences yesterday over his poor aim. It was like this; a partridge looked down upon the doctor from the top of a telephone pole at the Union National Bank corner. The doctor gazed at the stray visitor and brought forth a howitzer from the depths of his hip pocket and blazed away. The bird looked at him with a surprised expression and the doctor fired another volley. The bird again looked surprised and took wing and sailed away.”

In 1900, Wheeler was described in Compendium and History of North Dakota as “a Republican politically and is firm in his convictions, but takes little part in political affairs, and has never sought public preferment.” However, Wheeler served one term as alderman in 1913 and was mayor of Grand Forks from 1918 to 1920, during a time of community growth.

On the 4th of July in 1902, Wheeler took part in the first automobile race organized in North Dakota in Grand Forks. His steam-powered “Locomobile” overtook the two-block lead he had given to the gas-powered entrants, winning by 24 inches.

After his second wife died in 1914, Wheeler married a nurse, Ontario-born Mae M. McCulloch, on July 3, 1922. That December they were guests in Northfield of his first wife’s sister, Hattie Murray, as he visited old acquaintances.

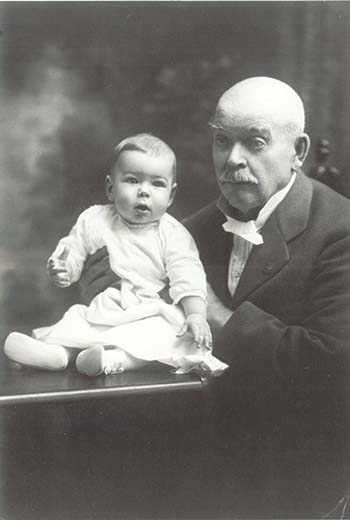

On May 9, 1924, the Northfield News brought the surprising news that the almost 70-year-old Wheeler and his wife Mae (in her early 40s) had a son, Henry M. Wheeler Jr., born on April 30. In an address about Wheeler given by Mason historian W. David Beach in the year 2000 to the Grand Lodge of North Dakota, there is a story that to celebrate this birth, “he responded by going to City Hall and raising the flag. It is said that in his excitement, he raised the flag in an upside down position, a universal sign of distress.”

On April 14, 1930, when his son was not quite six years old, Henry Wheeler Sr. died of heart complications at the age of 75. City offices were closed in his honor. Beach said that services were held in the Masonic auditorium and “the entire medical community of Grand Forks sat together as a body with many physicians from out of town.” The casket was then placed on a train to be buried in the family plot in Oaklawn Cemetery in Northfield. Earlier in April, Wheeler had been in town visiting Hattie Murray, who was seriously ill.

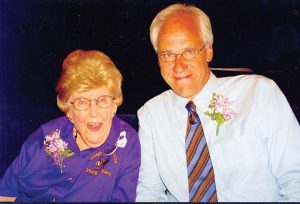

Wheeler’s third wife, Mae, died in Grand Forks on March 22, 1967, and is also buried at Oaklawn. Their son, Henry (known as Hank) Wheeler Jr., was interred at Oaklawn after his death at the age of 77 on July 26, 2001, at the Minneapolis Veterans Medical Center. An obituary said he was a graduate of the Pillsbury Military Academy in Owatonna, had served in the military in the China-Burma-India operations during World War II, then took up race car driving before moving to Rochester where he operated an insurance claims adjustment business. (He and his wife, Frances Rulien, had no children; she died in 1979.) In a Sept. 9, 1982, interview in the Rochester Post-Bulletin, Hank said, “It would be fun to climb the stairs to that upstairs room and pretend I was taking shots at Jesse James and his gang.” Hank moved to a Hastings veterans home in the 1980s.

In 1996, Hank Wheeler attended the Sept. 12-14 meeting of the James-Younger Gang Society in Northfield and was given lifetime membership in the Northfield Historical Society. Chip DeMann, leader of the current James-Younger Gang, tells me that plans had been made for Hank to portray his father, Henry Wheeler Sr., in the Defeat of Jesse James Days bank raid reenactments the year Hank died.

Surely this would have pleased the gunslinging Doctor Henry Wheeler. That year, 2001, was the 125th anniversary of the bank raid.

Thanks to Northfield Historical Society Executive Director Hayes Scriven, NHS curator Cathy Osterman and James-Younger Gang leader Chip DeMann for assistance with this column.

The Amazing Afterlife of the Dead Outlaws

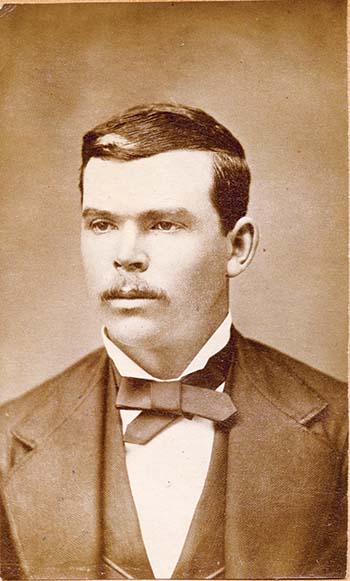

Northfield started its public celebration of the 1876 defeat of the James-Younger Gang in 1948, so there was no parade for the 50th anniversary of the raid in 1926. But on Sept. 10 the Northfield News printed the recollections of 72-year-old physician Henry Wheeler, who had moved from Northfield to Grand Forks in 1881. Under the picture of Wheeler was a caption, including this sentence: “Were one to visit his office at Grand Forks, he might be persuaded to show the skeleton of Clell Miller, the bandit whom he shot in the street battle of fifty years ago.”

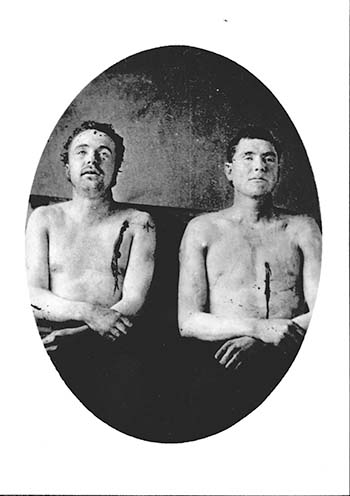

Wheeler’s skeleton was rumored to have been burned in an office fire. However, in the 1980s, a collector in Grand Forks acquired a skeleton said to have been given by Wheeler to the local Odd Fellows Lodge in the 1920s. In 2011, forensic scientist Dr. James Bailey, Professor Emeritus of Law Enforcement, Minnesota State University, Mankato, performed “craniofacial superimposition” on the Grand Forks skull, using the photo of Clell Miller taken by Ira Sumner shortly after Wheeler shot the outlaw. Dr. Bailey and three independent sources found remarkable similarities, suggesting the Miller skeleton may indeed be having an afterlife in North Dakota.

The afterlife story of Charlie Pitts (Samuel Wells), killed by posse members during the capture of the Younger Brothers two weeks later near Madelia, Minnesota, is even more bizarre. (Frank and Jesse James escaped back to Missouri.) The unclaimed body was sent to the state surgeon general, Dr. Frank Murphy, in St. Paul to be embalmed and was displayed for two days at the State Capitol (then at 10th and Wabasha). In March of 1877, Murphy then gave it to his nephew, medical student Henry F. Hoyt. In his 1929 book, A Frontier Doctor, Hoyt wrote, “Pitts was a fine specimen of physical manhood and I decided to retain and mount his skeleton for use in my office after my graduation. A good method of preparing a skeleton after dissecting is to bleach the bones under water for a year or so. Enlisting the help of one of my brothers, I packed the bones in an ordinary shoe box, putting in a few large rocks as sinkers. We drove out to the south branch of Lake Como, just inside the city limits of St. Paul, took the box out in a boat and sank it about at the middle of the lake.” Hoyt headed west. Many months later, a muskrat hunter discovered the box filled with bones with bullet holes and, until the matter was cleared up, newspapers speculated about the apparent murder victim submerged in the lake.

A skeleton said to be that of Pitts was exhibited in the Stagecoach Museum in the old west theme park in Shakopee, which was run by Ozzie and Marie Klavestad from 1951 to 1981. The skeleton was then donated to the Northfield Historical Society in July of 1981 when that museum closed. In 1982 the skeleton was sent to the Hennepin County Coroner’s office where tests concluded it was not Pitts. Dr. Bailey used DNA analysis in 2009 to reach the same conclusion. One further anatomical oddity: The Northfield Historical Society has a dried ear and portion of scalp from the private museum of William Schilling of Northfield which closed in 1981. Schilling had identified it as Charlie Pitts’ ear but DNA testing would be needed to verify that claim.

Wheeler Collection Comes Home to Northfield

Hayes Scriven, Northfield Historical Society Executive Director, remembers watching as museum tour guides filled in the back stories of the Northfield citizens who routed the James-Younger Gang on Sept. 7, 1876. Scriven told me that the panels of the exhibit, installed ten years ago, “were really following the bank raiders and not so much the townspeople” who were the “actual heroes of the failed raid.”

So when the opportunity came up for the Wheeler collection to be displayed at the Northfield Historical Society, thanks to the generosity of Norman Oberto and his family, a first step was taken toward an eventual overhaul showing the raid through the eyes of local heroes such as Henry Wheeler and A.R. Manning who had dispatched two of the outlaws.

Oberto, president of Imperial Plastics in Lakeville and a Northfield resident for 19 years, said he first met with Scriven in August of 2014. Oberto’s friend, Brett Reese, had suggested to Scriven that Oberto, who had been a collector of sports memorabilia and had an interest in history, might be able to help when the Historical Society was denied a grant to purchase the collection. Owners Gerald Groenewold and Connie Triplett of North Dakota had loaned the collection briefly to the Northfield Historical Society in 2013 and were ready to sell. Oberto was intrigued with the story of Wheeler’s heroism and impressed with Scriven’s passion and enthusiasm about trying to get the Smith carbine Wheeler used back to Northfield where it belonged.

Oberto told me that Wheeler’s story shows that “All of us can have a positive impact on our community in some way. We’re not all going to save the bank by shooting bank robbers today but you can treat people nicely, be a good citizen, help your neighbor and be an example” by doing the right thing as Wheeler did. On Nov. 8, 2014, Oberto purchased the Wheeler collection and then loaned it to the Northfield Historical Society for permanent display, courtesy of the Oberto family, which includes Norman Oberto’s wife Lori and daughters Emily, Lauren and Allison. The display itself, funded by the First National Bank, opened on June 16 of this year. To honor Wheeler further, Oberto has a licensing agreement with the city to develop a memorial Wheeler Park on about 2.7 acres off Jefferson Parkway.

Derk Hansen, who created pencil sketches of the bank raid in the 1980s, is doing a limited edition painting of Henry Wheeler, with 267 prints (that number chosen because the robbers made off with only $26.70 from the raid), along with a smaller, mass-produced version.

Brief History of the Smith Carbine of the Northfield Raid

Thanks to James A. Bailey, in the Wild West History Association Journal of Oct. 2012, we have the story “Tracing Edward Dampier’s Cavalry Issued Carbine Used in the Northfield Raid.” Bailey’s research established that seven people had owned the gun used by Henry Wheeler to kill outlaw Clell Miller and wound Bob Younger in 1876.

The first owner was Edward Dampier who had been issued the Civil War carbine when he enlisted in Minnesota’s volunteer cavalry, Hatch’s Independent Battalion, Company F, serving from 1864 to 1866. Bailey clarified in an email to me that “Dampier carried a Civil War firearm, but did not fight in the Civil War. This unit was assigned frontier duty in the event of Native American uprising.” Dampier mounted the .50 caliber Smith carbine on the wall of the Dampier Hotel (which he had opened in Northfield in 1875). After Wheeler used this gun to kill Clell Miller during the 1876 raid, the carbine remained with Edward until his death in 1889, when his son Charles Dampier (Henry Wheeler’s friend who had been a fellow University of Michigan medical student) inherited it. Wheeler borrowed the gun to display in his office and was given the gun after the death of Charles Dampier in 1923. Wheeler’s third wife, Mae McCulloch Wheeler, took charge of the gun after he died in 1930 but then gave it to their son, Henry M. “Hank” Wheeler Jr. In 1973, Hank Wheeler sold it to a friend in North Dakota, Charles R. Dickson, who had become the husband of Mae Wheeler’s housekeeper, Bertha Lund, after Lund left Mae’s employment. Dickson sold the carbine in 1980 to Gerald Groenewold of Grand Forks, North Dakota.

And we can now add the Nov. 8, 2014, date when Norman Oberto of Northfield became the eighth owner and loaned the carbine for permanent display at the Northfield Historical Society.